The long silence on The Holy Rover is a result of a trip my husband and I took over the past three weeks to see our son Carl, who is spending a semester studying in Belgium. I had never been to Belgium, Bob had never been to continental Europe, and before you know it we had planned a trip that also included Germany, France and Amsterdam (in the military this is known as “mission creep,” but it also happens to travel writers).

Given our interests, it’s not surprising that our journey took us to many holy sites, some major, some obscure. Over the next weeks, you’ll be hearing about them, making this winter a kind of Holy Rover Channels Rick Steves. I hope you’ll come along with me, as there are a lot of people and places I’d like to introduce you to.

We begin in the Belgian city of Leuven. Before Carl landed there I knew very little about Belgium, and even after our visit I’m still trying to figure out the country. Despite being about the size of a postage stamp on most maps, Belgium is a sometimes-fractious blend of two distinct cultures. The north is Flemish (a form of Dutch) and the southern region is home to the French-speaking Walloons.

As far as I can tell, pretty much everything in Belgium gets divided. For example, Carl’s temporary home is Leuven to the Flemish and Louvain to the French. In the 1960s there was so much acrimony at the city’s main university that the school split into two parts (they even divvied up the library books). The historic campus in the heart of the city conducts itself in Flemish, while a newer campus on the outskirts does so in French. One can either find this depressing (is there any hope for world harmony if even Belgian academics can’t get along?) or somewhat amusing. I found it both. Carl is studying at the historic campus, and I just hope he doesn’t get caught in the cultural crossfire before he leaves.

If you’re a beer lover, you may already have heard of Leuven, which prides itself on being the Beer Capital of the Beer Capital of Europe. I found it totally charming, with its cobblestone streets, cozy pubs, and Oude Markt (old market square). But what really captured my heart, to the point of wanting to move there, was a portion of the city known as the Grand Beguinage.

If you think of beguine as only a dance, you’re missing a nearly forgotten but important part of Christian history. Beginning in the 13th century, a movement began of lay women who lived in loosely structured religious communities while serving the poor and sick. With many men killed in the Crusades or lost to the myriad dangers of medieval life, there were a lot of unattached women in Europe. In the Low Countries of Holland and Belgium in particular, hundreds of Beguine communities formed. Their members did not make permanent vows and were not affiliated with any monastic order, but instead pledged more flexible vows that typically involved piety, simplicity, chastity and service to others. Some eventually left their communities, while others spent the remainder of their lives as Beguines.

These communities varied greatly in size, with some Beguines living alone and others residing in walled neighborhoods that housed a thousand or more women, typically in close proximity to a church. Those who did not come from wealthy families supported themselves by manual labor or teaching.

The Beguine movement flourished for centuries in Europe, despite drawing at times the ire of the official church. During an era when single women were highly vulnerable, these enclosed communities provided a safe haven as well as spiritual sustenance.

The more I learn about the Beguines, the more I want to revive the order. What a splendid model they created, a kind of halfway point between monastic and secular life (I also love what the elected leaders of each community were called: The Grande Dame). Now there’s a title to aspire to.

And when I saw the digs these women had in Leuven–well, I was ready to sign up on the spot.

Even in a city full of picturesque neighborhoods, the Grand Beguinage of Leuven seems like it belongs in a fairy tale. The community was founded in the early-13th century and at its height housed 300 women. Though their numbers gradually dwindled, Beguines lived here until the 1980s. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the enclosure is maintained by the University of Leuven, which uses it as a residence facility for students, professors and visitors. Thankfully, the public is welcome to stroll through the area, which is exactly what we did on a brisk November afternoon, marveling at its canals, foot bridges, small brick homes with steeply pitched roofs, and winding cobblestone streets.

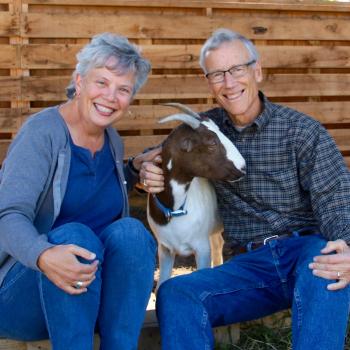

My new home is pictured above. In the event that Bob goes off to the Crusades (unlikely, I realize, but one never knows), I daydream of moving into this little cottage by the canal, a block away from an equally charming church and hopefully with a group of like-minded women friends. It’s not that I don’t like men–some of my best friends have a Y chromosome–but I think it must have been a wonderful existence for those Beguines. Living in community, supporting each other, and serving the poor, they always had someone to talk to and someone to care for them. And while I haven’t been able to find historical evidence for this, I’m almost certain that many of them kept cats. Certainly the neighborhood is made for them.

I’ll tell you a bit more about the Beguines when we travel to Bruges, but in the meantime let me leave you with part of an obituary that The Economist published on Marcella Pattyn, the last Beguine, who died on April 14, 2013:

In her energy and willpower she was typical of Beguines of the past. Their writings—in their own vernacular, Flemish or French, rather than men’s Latin—were free-spirited and breathed defiance. “Men try to dissuade me from everything Love bids me do,” wrote Hadewijch of Antwerp. “They don’t understand it, and I can’t explain it to them. I must live out what I am.”

Prous Bonnet saw Christ, the mystical bridegroom of all Beguines, opening his heart to her like rays blazing from a lantern. But a Beguine who was blind [as was Pattyn] could take comfort in knowing … that Love’s light also lay within her…

When she was known to be the last, Marcella Pattyn became famous. The mayor and aldermen of [her home city of] Courtrai visited her, called her a piece of world heritage, and gave her Beguine-shaped chocolates and champagne, which she downed eagerly…The story of the Beguines, she confessed, was very sad, one of swift success and long decline. They had caught the medieval longing for apostolic simplicity, lay involvement and mysticism that also fired St Francis; but the male clergy, unable to control them, attacked them as heretics and burned some alive. With the Protestant Reformation the order almost vanished; with the French revolution their property was lost, and they struggled to recover. In the high Middle Ages a city like Ghent could count its Beguines in thousands. At Courtrai in 1960 Sister Marcella was one of only nine scattered among 40 neat white houses, sleeping in snowy linen in their narrow serge-curtained beds. And then there were none.