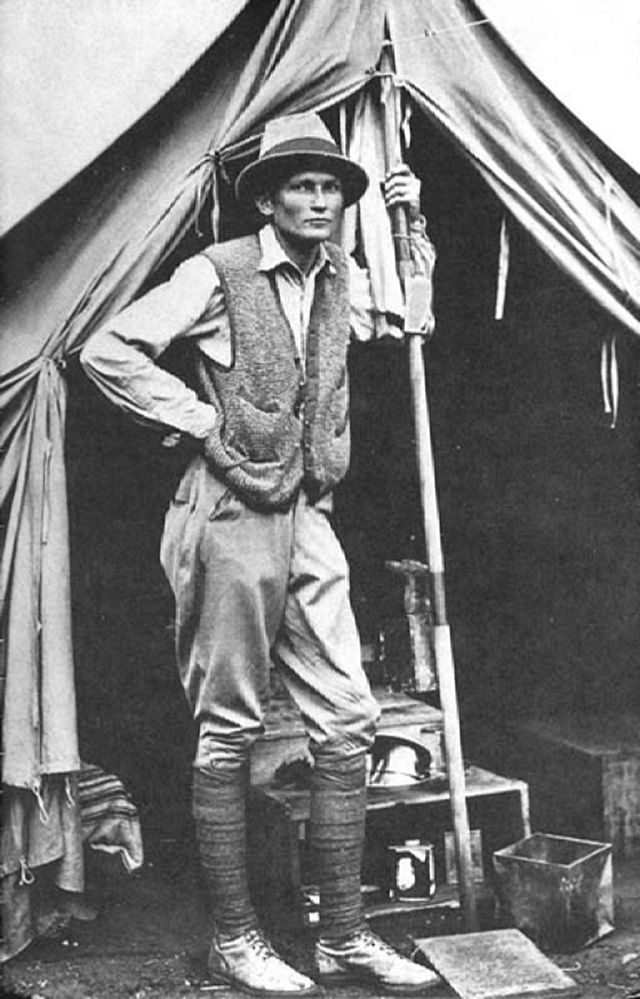

In 1911, Yale professor Hiram Bingham III made a discovery that catapulted him to international fame and put a remote site in the Peruvian Andes on the bucket list of generations of travelers. In Bingham’s book Lost City of the Incas, he describes the moment:

“Hardly had we left the hut and rounded the promontory than we were confronted by an unexpected sight, a great flight of beautifully constructed stone-faced terraces, perhaps a hundred of them, each hundreds of feet long and ten feet high. Suddenly, I found myself confronted with the walls of ruined houses built of the finest quality Inca stone work. It was hard to see them for they were partly covered with trees and moss, the growth of centuries, but in the dense shadow, hiding in bamboo thickets and tangled vines, appeared here and there walls of white granite carefully cut and exquisitely fitted together…The sight held me spellbound…I could scarcely believe my senses as I examined the larger blocks in the lower course, and estimated that they must weigh from ten to fifteen tons each. Would anyone believe what I had found?”

Bingham in one sense didn’t “discover” Machu Picchu, for its location had long been known to the natives of the region, as well as to a few Europeans who had trekked through the surrounding jungle. But he was the one who brought the site to the world’s attention, thanks to his Ivy League position and his association with National Geographic Magazine, which publicized his explorations in multiple articles. It also helped that Bingham had a zeal for self-promotion and a substantial ego (in fact, he would later become the inspiration for the movie character Indiana Jones).

So what, exactly, did Bingham find? The answer is complicated, for while much is known about Machu Picchu, many mysteries remain.

Machu Picchu was built in the 15th century during the glory years of the Inca Empire, most likely by Pachacuti, the greatest of its rulers. Its physical location is remarkable, occupying a narrow promontory of land surrounded by mountain peaks and encircled on three sides by a loop of the Urubamba River. It’s been called the world’s most perfect blend of architectural and natural beauty.

The site’s buildings fill much of the space between two peaks: Machu Picchu (which means “old peak” in Quechua) and Huayna Picchu (meaning “young peak”). About 60 percent of its structures are original, while the rest have been rebuilt. The hilltop settlement includes three main areas: a royal and sacred section, a secular quarter where workers lived, and more than 100 terraces where crops were grown. Machu Picchu is a marvel of civil engineering, linked by staircases and kept dry in the frequent rains of the cloud forest by an intricate drainage system. Its construction methods showcase the highest standards of Inca masons, with its huge building blocks shaped so precisely they needed no mortar.

One of the puzzles of Machu Picchu is that it did not have any obvious military or strategic use. Some scholars speculate that it was the equivalent of Camp David for the U.S. President—a royal retreat away from the Inca capital of Cusco, which lies 50 miles to the southeast. The site was occupied for only about a century and then was abandoned after the Conquistadors took control of the Inca Empire. It was never discovered by the Spanish during the Colonial Era, and gradually jungle vegetation grew over much of it.

So why do pilgrims from around the world flock to this isolated site? More than physical beauty draws them here, I think, for there is ample evidence that from its very beginning, Machu Picchu had great spiritual significance. Its location was likely chosen in part because of its proximity to mountains and a river considered sacred by the Incas. Its plazas include multiple shrines, temples and carved stones, some of which are oriented to astronomical events such as the winter and summer solstices and spring and fall equinoxes.

Take, for example, a carved block of granite known as the Intihuatana (see below), which is arguably the most sacred spot at Machu Picchu. Its name is Quechua for “the tether of the sun.” The term refers to the theory that the stone was once used as a kind of astronomical calendar. At the spring and fall equinoxes, the stone casts virtually no shadow, leading (perhaps, for all of this is speculation) to the belief that the post somehow kept the sun from retreating farther from the earth.

For years tourists were allowed to place their hands on the Intihuatana, but now, alas, it is roped off, so I can’t report firsthand whether it’s full of energy, as some New Age enthusiasts claim. But its position and careful shaping suggest that this stone was considered highly significant by its creators. Another indication is that similar stones have been found at other sacred sites in Peru. All were damaged by the Spaniards, who clearly saw them as representing something important to the native people and thus a threat to their control.

I’ll tell you more about my own personal impressions of Machu Picchu in my next post, but first I must confess that I’m actually a little embarrassed by how little effort I expended to get there. Before visiting, I had the idea that Machu Picchu is only reached by hacking through dense jungle, a la Indiana Jones. Instead, I took a bus and train from Cusco and then a bus to the promontory where Machu Picchu sits. If I visit again I’ll take the Inca Trail, the arduous hiking route that leads up and down the mountains before emerging at Machu Picchu. It felt a little bit like cheating to arrive there so easily.

But no matter how you arrive at Machu Picchu, your reaction is likely to be the same: awe. That’s a word that gets tossed around so much that it’s lost much of its original meaning. To be awestruck means to be filled with a mixture of reverential respect, wonder and a little bit of fear. As I rounded the corner and got my first full view of Machu Picchu, those emotions flooded over me. The site’s visual impact felt almost physical in its force.

A light rain was falling and clouds swirled around the buildings and the terraces that are cut into the steep hillsides like stairways for giants. It seemed almost impossible that human hands could have built this grand settlement in such an isolated spot, particularly before the age of modern technology. Little wonder that Machu Picchu has been named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World.

One of the most intriguing theories about Machu Picchu has been advanced by the scholar and explorer Johan Reinhard, author of books that include Machu Picchu: Exploring an Ancient Sacred Center. His research suggests that Machu Picchu formed the cosmological and sacred geographical center for a vast region. It was the hub of a spiritual web, connected to other holy sites in the region and to celestial bodies in the sky, surrounded by deities who lived in the surrounding mountain peaks and the river far below. Perhaps that’s why it’s easy to feel the pull of the sacred at Machu Picchu, as if you are also being drawn into that web.

There are only a few holy sites in the world where so many factors come together: physical grandeur, architectural beauty, and an interweaving of sky, mountains, jungle, river and clouds. That is Machu Picchu, as dazzling now as when it was a jewel in the crown of the Inca Empire.

A Few Practical Suggestions for Visiting Machu Picchu: As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, access to Machu Picchu is tightly controlled. International travelers fly into Lima and then to Cusco. From there, you can travel to Machu Picchu either by Inca Rail or by hiking. Hikers must go with a licensed guide and make reservations well in advance. Access to the Inca Trail is limited to 500 hikers a day. The classic route is a five-day expedition, but shorter options are also possible.

The less adventurous can board a train that leads to Aguas Calientes, the small town at the base of Machu Picchu. It’s best to stay overnight there (I highly recommend the Inkaterra Machu Picchu Pueblo Hotel, which has a lovely forest setting and has received awards for its commitment to ecologically sustainable practices). The next morning, take an early morning bus to the summit to avoid the crowds. The busiest season at Machu Picchu is June to September, and visiting during the shoulder seasons of April-May and September-October is highly recommended. For more information, contact the Peru Office of Tourism.