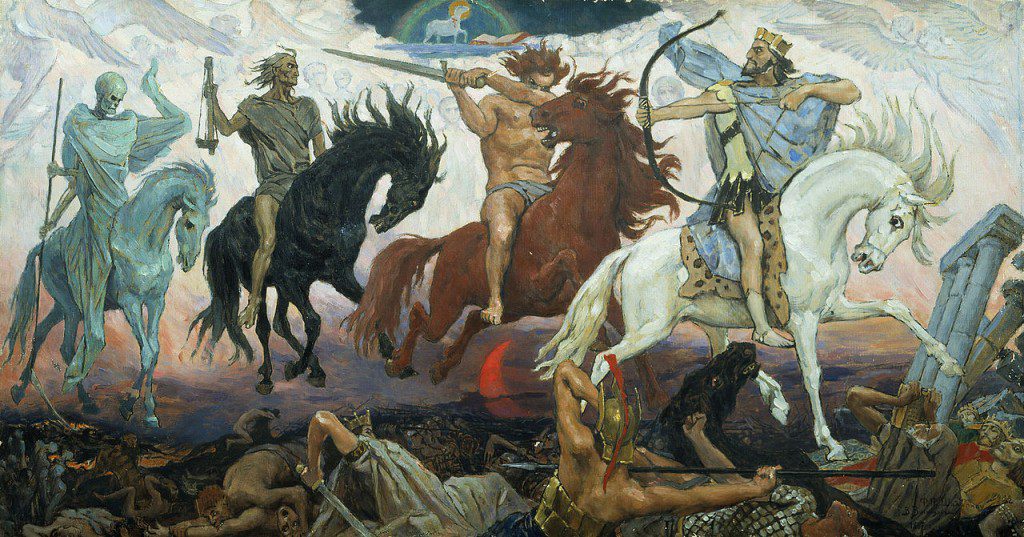

Apocalypse. The end of the world. The last great cataclysm.

It’s one of religion’s thorniest concepts. And it’s found in cultures throughout the world.

I’ve been asked by National Geographic to be one of a number of bloggers responding to The Story of God with Morgan Freeman, which is currently playing on Sunday evenings on the National Geographic Channel. I’ve gotten an early screening of this coming Sunday’s episode Apocalypse.

In this episode Freeman travels to Jerusalem, to the Judean desert where the apocalyptic Essene Community lived in the first century A.D., and to a scientific lab where researchers are studying how people react to pain. He speaks with a former Islamist radical, a Tibetan lama, and survivors of Hurricane Katrina. It’s a compelling, thought-provoking program.

I consider myself pretty well-versed in religious matters, but the end-of-days wasn’t on my spiritual radar for a long time. I was raised a small-town Lutheran, and Apocalypse was something that other Christians worried about. There was a faint whiff of bad taste about it, in fact. It was the preoccupation of fire-and-brimstone preachers on TV and the uneducated.

But as an adult, I’ve come to learn that apocalyptic beliefs are more significant and ubiquitous that I’d realized. They’re present in various religions, of course, particularly Christianity and Islam. But I hear echoes of them in more secular settings as well, especially from friends who are filled with fear at threats that include environmental degradation, global warming, the spread of Ebola/Zika/Name-The-Terrifying-Disease, the rise of politicians they despise, etc. There are always many reasons to be terrified.

I’ve watched loved ones go through their own personal apocalypses, too, tragedies so great that they seemed almost Biblical in scope. Some of them were able to go on, and some weren’t. But even the survivors bear permanent scars.

So I think part of this universal human fascination with the end-of-days springs from the recognition that everything we have is at risk. It’s all temporary and vulnerable, a fact that becomes blindingly obvious when we are sleepless at 3 o’clock in the morning.

There’s something liberating, I recognize, about turning those fears into a grand cosmic drama. Your feeling of powerlessness can be lessened by thinking that this is all part of a divine plan that is being worked out on a global scale. If you’re a victim of injustice now, there will be retribution for those who are hurting you. Both religious and secular people find apocalypse a powerful way to make meaning out of chaos.

I’ve been fortunate not to have gone through a personal apocalypse on the order of a Katrina, a major health crisis, or great suffering. But few of us get to our 50s without some scars. And so I have sympathy for those who try to put their trials in a larger context.

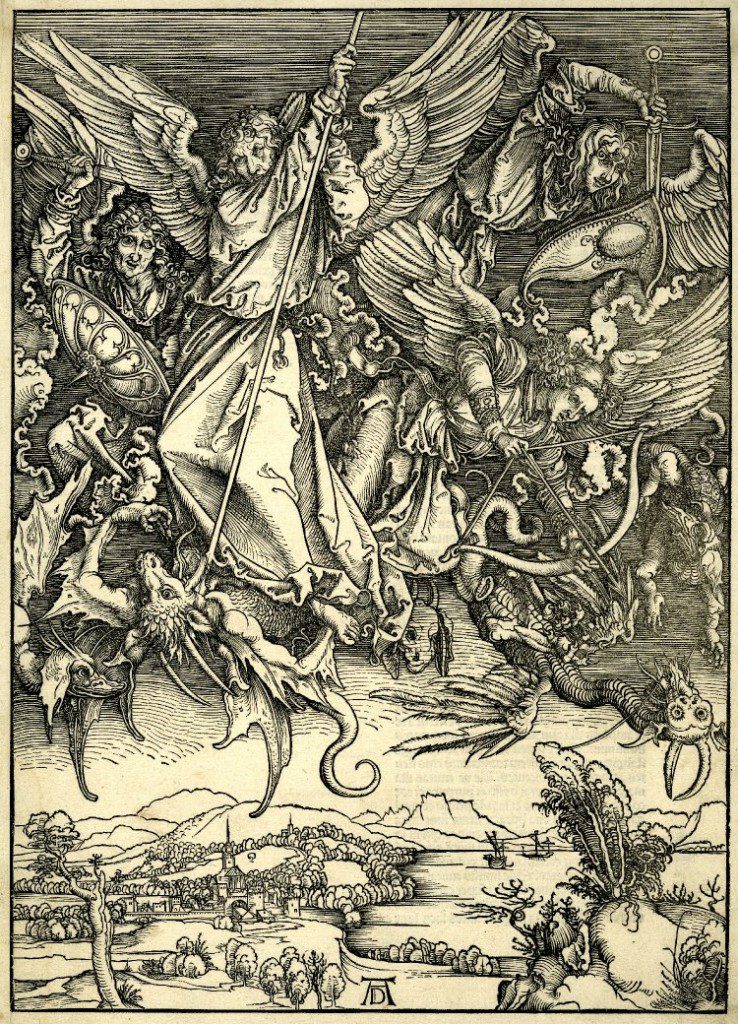

But for myself, the apocalyptic writings of Revelation, or the Book of Daniel, or the latest bestseller on how the world-is-going-to-hell-in-a-handbasket aren’t of much interest.

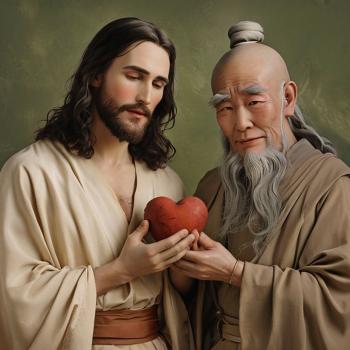

Though I’m a Christian, I’ve found the Buddhists to have the wisest perspective on these matters (a viewpoint that Morgan Freeman presents very well in the Apocalypse episode). There are profound lessons to be found in disintegration, failure, and sadness. We can approach the turmoil with curiosity, asking what it can teach us.

This process can awaken us to our true natures—for the word Buddhism comes from the Sanskrit budhi, which simply means to “wake up.”

“There is no end, only change,” says a Tibetan Buddhist teacher to Freeman.

In this there may be some connection with apocalypse after all. For the word apocalypse comes from a Greek word meaning “to lift the veil.” It doesn’t have to mean a violent end—instead it can mean a revelation of hidden truths.

And while that process can be life-changing, it doesn’t have to be terrifying.

Stay in touch! Like Holy Rover on Facebook: