Today’s post is a sermon I gave on Sunday at New Song Episcopal Church in Coralville, Iowa.

A friend of mine tells the story of bringing someone to an Easter Vigil service one year, someone who wasn’t very familiar with Christianity but was curious about Easter. At the end of the long service, he asked her what she thought of it.

“Weeeeell,” she said, clearly trying to be polite. “There sure was a lot about Jesus in it.”

And indeed there was. The services and rituals of Holy Week, more than any other part of the church year, are all about Jesus.

Think of the unusual things we do this week to connect ourselves with him—-we wave palm branches, we wash each other’s feet, we recall his last walk through the city of Jerusalem, we put ourselves at the entrance to the empty tomb. All within the space of just a few days.

This week, more than any other, is shaped by the power of imagination. We don’t normally think of the imagination as a spiritual tool, which is unfortunate. St. Ignatius of Loyola didn’t make this mistake: imagination is one of the foundations of his well-known Spiritual Exercises. Each day you’re asked to put yourself into one of the Biblical stories. You’re asked to imagine the sounds, smells, tastes, and sights of the scene, how it feels to wear rough-woven cloth and eat dried fish from the Sea of Galilee and feel the Judean dust between your toes.

So today I want to take you on a trip of that imaginary sort—-to Jerusalem. But not as it was in Jesus’ day, but how it is today.

If we were in Jerusalem this morning trying to have a spiritual experience, we’d probably be frustrated. I certainly was when I visited several years ago. I was on a trip that packed for too much in, one of those guided tours that puts centuries of history into a blender and spits them out high speed.

In one day we saw the Mount of Olives-Garden of Gethsemane-Western Wall-Church of all Nations-Church of the Holy Sepulchre-Garden Tomb. I knew quite a bit about Jewish and Christian history before arriving, but even I was confused by the barrage of information. I kept mixing up the Sadducees with the Samaritans. I had to struggle to keep track of who-was-who among the many badly behaving relatives of Herod the Great.

I was relieved to have the next day free to explore the city at my own pace. A short walk from our hotel brought me to the walled Old City, where I stepped into a labyrinth of streets, alleyways, and merchants stalls. The air was filled with the smells of spices, cooking meats, and the musty decay of old buildings.

As I walked I passed a steady stream of people: Orthodox Jews wearing fringed shawls, black-robed Greek Orthodox nuns, Israeli soldiers, groups of Christian pilgrims in matching T-shirts, and elderly Muslims fingering prayer beads.

With so much history and conflicting political agendas coming together in the Old City, its humming vitality contained a hint of unease. I remembered the description of the city given by Josephus, the first-century Roman-Jewish historian: Jerusalem, he said, is a golden bowl full of scorpions.

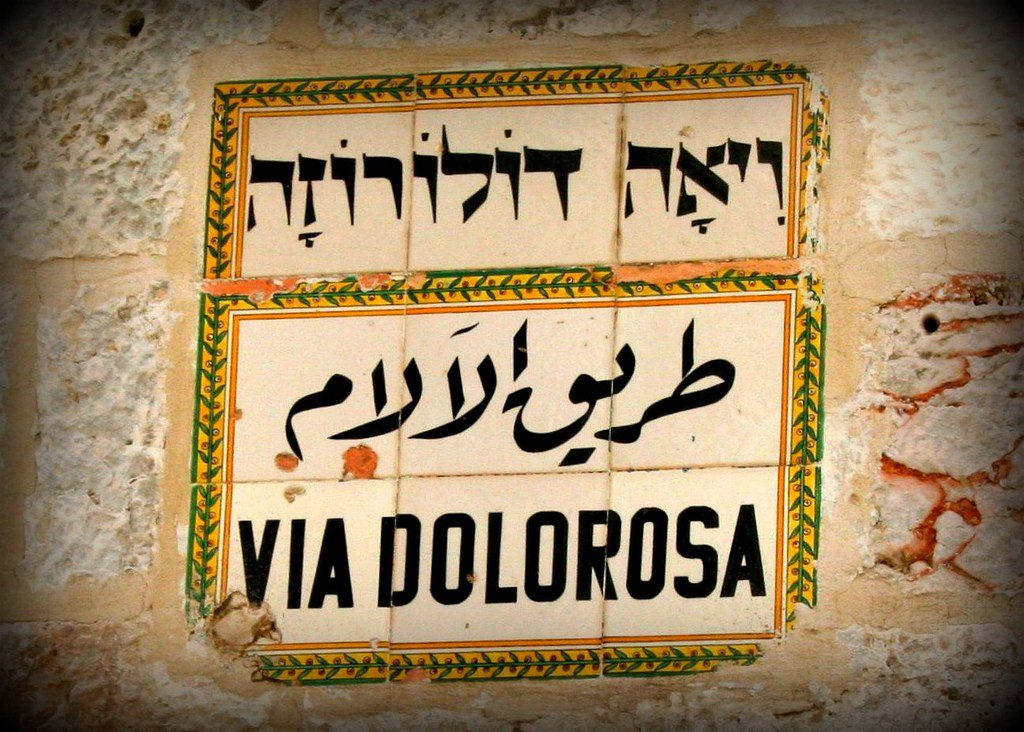

As I walked, I traced the Via Dolorosa, the Way of Sorrow, which marks the path followed by Jesus from the Roman judgment court to Golgotha. The route includes fourteen stations, nine along the narrow streets and five inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the place where Jesus is believed to have died and been resurrected.

Was this the exact route taken by Jesus? Probably not. But historical accuracy is not the point. Jesus did walk through the city on his way to be killed, and then, as now, Jerusalem was a bustling place, full of the calls of shopkeepers and the busyness of people going about their ordinary routines. The normal rhythms of Jerusalem did not stop for that tortured journey, and neither does the Old City keep quiet for the pilgrims who walk the Via Dolorosa today.

So here’s the problem: it’s hard enough to have a spiritual experience in a quiet church, but it can be almost impossible to have one in the midst of a bustling, chaotic world. For the holy is always intertwined with the ordinary. And the sacred always hides best in plain sight.

You’ve likely been on your own private Via Dolorosa a time or two in your life, a time of suffering so great you didn’t know if it would ever end. Or you’ve watched a loved one walk a Way of Sorrow, maybe through illness or tragedy or addiction. And you can certainly see strangers on a Via Dolorosa every day in the halls of the University of Iowa Hospital. Most people you see there are likely to recover and return to their ordinary lives. But there are others who are clearly walking through the valley of the shadow of death.

We shouldn’t be too harsh, really, on the shopkeepers of Jerusalem, then or now, for ignoring those who walk a Way of Sorrow is something we all do. We all prefer to look away from watching other people’s pain.

And perhaps that’s one of the reasons why it’s important to go through Holy Week with open hearts. Each year, we have the chance to be reminded of the suffering of the innocent. I don’t think Jesus wants us only to remember his. I think he wants us to see his Via Dolorosa as a window into the suffering of those around us.

Let’s go back to Jerusalem, shall we? For as we continue on the Via Dolorosa there, we come to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (sepulcher being another word for tomb). It’s one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Christianity—a weird, confusing, magnificent barn of a place.

You’d think this church would be serene and contemplative, but it’s just the opposite. In fact, it’s been the focus of fighting for centuries. The First Crusade in the 11th century was partly sparked by this church falling under Muslim control. Even under Christian rule, this holy site has seen centuries of fussing and feuding.

Two Muslim families have been in charge of opening and shutting its doors each day since the 13th century, for example, because of so many squabbles between the various Christian denominations who have control over different parts of the sanctuary.

When I visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, there were crowds of people there, some in a reverential mood and others snapping pictures and talking loudly. Clergy dressed in ornate vestments strode through the crowds, immersed in a complicated set of rituals that didn’t seem to involve anyone but themselves.

When you enter the church, you first climb the stairs to Golgotha, a shrine marked with a gilded Greek Orthodox altar. Descending the stairs, you pass by the Stone of Unction, which commemorates the spot where Jesus’ dead body was anointed and wrapped for the grave, and then you come to the sepulchre itself, the spot where Jesus is said to have lain before his resurrection.

When I approached this shrine, my heart sank as I saw the long line of people waiting to enter it. I watched them for some time, debating whether I wanted to spend at least a half hour in line. As on the streets outside, I wrestled with my frustration at the crowds and the commotion.

Here I was at one of the holiest places in all of Christendom, and all I could think about was how much my feet hurt and how great it would be to take a cool shower.

Tired and discouraged, I turned away from the shrine and headed to another part of the church, away from the crowds to a spot that I recalled from our tour the previous day: an unadorned room empty except for a somewhat-shabby altar. To one side was the entrance to a cave hewn out of rock, a space so small that a person could barely fit within it. Inside the darkness of the cave, a small lamp was burning.

I remembered our guide saying that according to tradition, this cave is the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea. He said, “All the crowds go to the sepulchre, but I think this spot may well have been the place where Jesus’ body was laid.”

I stood for a long time in that room, not caring much whether the guide’s guess was true. It was quiet there, for one thing, the noise of the crowds in the main sanctuary nearly inaudible. And I was mesmerized by the oil lamp that burned inside the cave, a light that created a halo of radiance in the shadows. It made me think of that wonderful line from the opening verses of the Gospel of John: “The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.”

Seeing that flickering light, it struck me that resurrection was far more likely to happen here than amid the crowds in the main church, for rebirth needs darkness and quiet. I watched the candle for a long time before finally walking out of the room, through the church, and out into the crowded alleyways of the Old City once again.

When I think of visiting Jerusalem, what I remember most vividly is that candle burning in the darkness.

It’s a dark world, isn’t it? That’s true in the Middle East, and it’s true in the U.S., and it’s true in the hallways of the University of Iowa Hospital. But it’s also a world in which resurrection happens.

So during this week, let us light a candle in the darkness, both for ourselves and for this troubled world. And let us remember that resurrection needs quiet. Perhaps it’s a good thing that the rest of the world is so loud and busy that these places of rebirth get nearly forgotten. Seeds need darkness in order to germinate, there underneath the soil.

May these seeds grow in us, this Holy Week.