Not long ago a friend told me about a neighbor who was unexpectedly generous in helping her with a volunteer project, even recruiting her husband to assist. “They’re Mennonite—maybe that has something to do with it,” my friend said.

After visiting the Amish-Mennonite communities in northern Indiana, I think it likely that their religious affiliation has everything to do with it.

While the Amish get most of the attention (those buggies and bonnets tend to draw the eye), the Mennonites are an equally interesting community. You might think of them as cousins to the Amish, as they share a common Anabaptist heritage and many Mennonites have an ancestor who at some point left the Amish church.

But while the Mennonites have similar religious beliefs to the Amish, they don’t have the same firm boundaries in relation to the larger world. They tend to be more accepting of technology and interpret their commitment to simplicity in a greater variety of ways. They may wear distinctive clothing (for example, some Mennonite women wear white caps), but generally you probably wouldn’t be aware that you were speaking to Mennonites unless they told you their religious affiliation.

On the other hand, if you look at what they do, Mennonites are as distinctive as their Amish cousins.

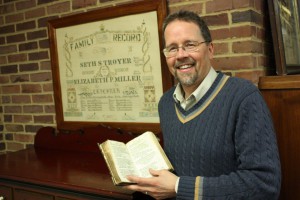

I got the chance to learn about the Mennonites on the campus of Goshen College in Goshen, Indiana. This is the country’s largest Mennonite institution of higher learning. About half of its 1,000 students are Mennonite (while Amish children almost never attend school past eighth grade, the college has also had a few Amish students in its history). The college is home to the Mennonite Historical Library, which has 65,000 books as well as genealogical records, maps, periodicals, quilts, toys, furniture, and folk art.

On my visit I had the privilege of speaking with John D. Roth, the library’s director. When I asked him what were the most distinctive characteristics of the Anabaptist groups, he spoke first about their consistent witness to the gospel of peace. “I think their own history of persecution in Europe has given them a deep empathy for those who are oppressed,” he said. “When they first came to this country, they were moved by the incredible injustices of slavery and began working for the abolitionist cause. And throughout the ensuing years they have often been pacifists and conscientious objectors to war.”

As commentators on this blog have mentioned recently (thank you, Anne), the Mennonites also have a remarkable commitment to helping those in need. These practical and hard-working people are among the first to respond to tragedies and natural disasters and typically remain long after other volunteer groups have left.

“Lay service is part and parcel of the Mennonite faith,” Roth said. “Students at Goshen College, for example, are required to spend a full semester in a developing country. The Mennonites recognize that the Body of Christ knows no boundaries.”

According to Roth, the Mennonites have recently begun to move to an even more active commitment to peace-making. The Victim-Offender Reconciliation Movement (which started in Elkhart, Indiana) is one example of a small-scale Mennonite initiative that has captured the attention of the larger culture.

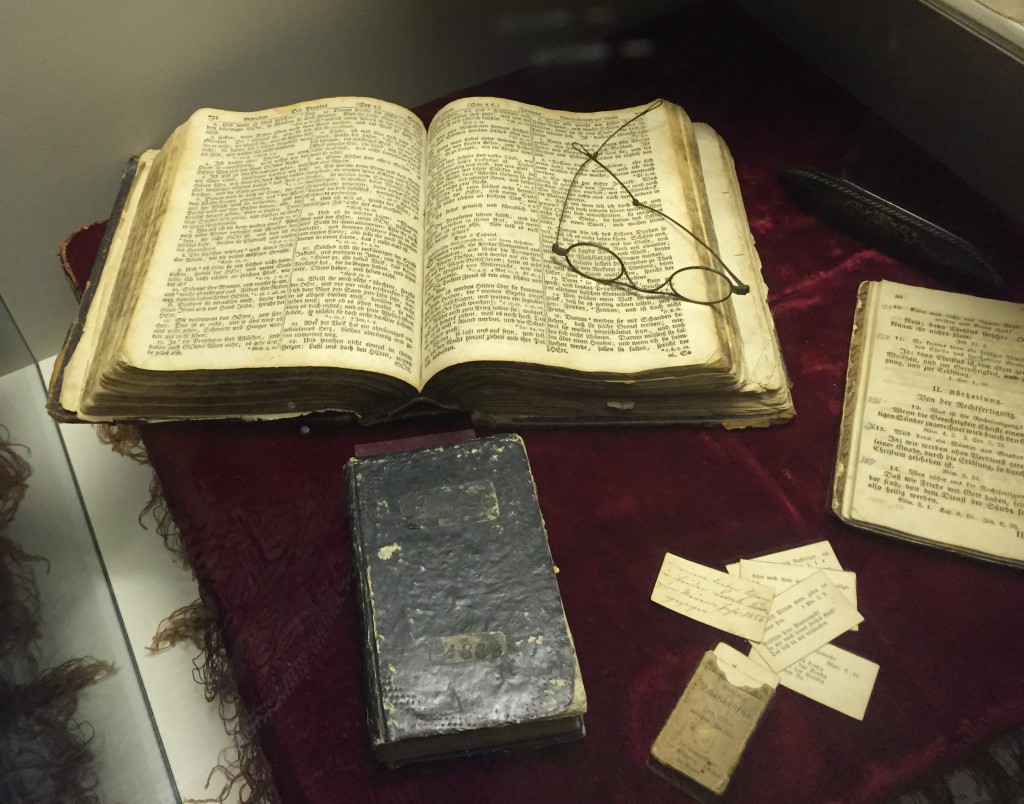

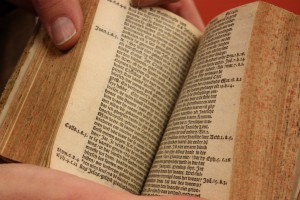

During my visit to the library, I was able to see one of the rarest and most valuable books in its collection: a 1724 edition of the Martyrs Mirror. First published in 1659, the book describes the sacrifices made by Christian martyrs, particularly those in the early Anabaptist movement. The book became an important devotional manual for the Mennonites and has been especially influential in conveying the principles of non-violent resistance.

One of the book’s stories is that of Dirk Willems, a Dutch Anabaptist who died in 1569. Willems was fleeing from arrest by the local authorities when he came to some water thinly covered with ice. While he safely crossed it, one of his pursuers wasn’t so fortunate and slipped into the freezing water. As the man’s companions stood on the shore and refused to come to his aid, Willems stood on the other shore, agonizing about what to do. Then he recalled the words of Jesus: “Love your enemies; bless them that curse you; do good to them that hate you.” Willems carefully ventured out onto the ice and managed to save his pursuer’s life.

And then, proving that no good deed goes unpunished, Willem was captured, tortured, and put to death by the authorities.

This story has been told and re-told countless times by the Anabaptists. Willem’s steadfast faith and rescue of his persecutor is held up as an ideal to be emulated–and his unjust death is a sober reminder not to expect the world to reward you when you do something good.

I’m going to remember that story the next time I hear of the Mennonites coming to the aid of those in need. Somehow the fact that they treasure this tale makes me think even more highly of these quiet and unassuming people who do so much good.