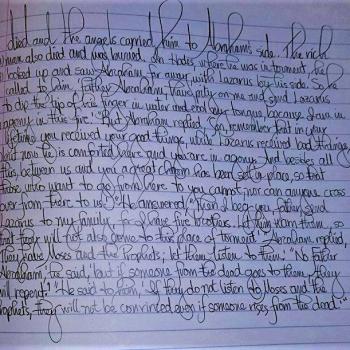

Someone asked me Sunday “how far I am” in handwriting the New Testament. I started December 31, 2010. As of this morning, I have just finished the first book, Matthew. Only 26 books to go! On the plus side, Matthew is one of the longest New Testament books. The next book, Mark, should move along much more quickly if my current pace can continue.

Matthew 6 is the chapter for today, known for being the location of the Lord’s Prayer. Interestingly, this prayer is really more accurately described as how Jesus taught his disciples to pray. Interestingly, these verses contain some textual variants in the Greek manuscripts toward the end of the prayer. The official word, from the notes of the NET Bible, state:

Most mss (L W Θ 0233 Ë13 33 Ï sy sa Didache) read (though some with slight variation) ὅτι σοῦ ἐστιν ἡ βασιλεία καὶ ἡ δύναμις καὶ ἡ δόξα εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας, ἀμήν (“for yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever, amen”) here. The reading without this sentence, though, is attested by generally better witnesses (א B D Z 0170 Ë1 pc lat mae Or). The phrase was probably composed for the liturgy of the early church and most likely was based on 1 Chr 29:11-13; a scribe probably added the phrase at this point in the text for use in public scripture reading (see TCGNT 13-14). Both external and internal evidence argue for the shorter reading.

In other words, the earliest manuscripts do not include “for yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever, amen.” This doesn’t make these words bad, just not original.

This important observation highlights something my little handwritten Bible experiment reveals: handwriting manuscripts of the New Testament was not a perfect science. Each ancient copy includes slight differences from one another. As a result, much study is required to determine which manuscripts are earliest, of the best quality, and ultimately, determine which wording is most likely the original. But don’t be worried. It’s not like we only have one or two copies to compare. There are about 5,800 copies or portions of the Greek New Testament from before the printing press, plus thousands of early translations in Latin, Coptic, and Syriac.

As my Greek professor Dr. Daniel B. Wallace, one of today’s top New Testament textual critics, taught in my course with him, “I am confident the original wording is in the Greek critical text or in the footnotes.” There is no doubt regarding the wording of the vast majority of the New Testament. Of those places where there is some difficulty in determining which reading was original, there is not some unknown, mysterious missing wording, but rather a choice between a couple of options cited in the apparatus of modern editions of the Greek New Testament.

All this to say, if you see a shorter ending to the Lord’s Prayer in modern translations, it’s not because the translators have turned away from God or are tampering with the text. They are providing the most accurate translation based on the best information available from 2,000 years of research. For that, we should all stand in appreciation of those whose lives are committed to understanding Scripture and providing the tools we use to better grow in our walk with Jesus.

+++

Dillon Burroughs has written, co-written, or edited over 60 books, including the upcoming devotional work Thirst No More (October 2011). He served as an associate editor for The Apologetics Study Bible for Students and is a graduate of Dallas Theological Seminary. Find out more at DillonBurroughs.org.