In his popular story, “The Bear,” William Faulkner once described the wilderness of the South as having soils brutalized by whites and saturated by the blood of massacred Indians and beaten slaves, a tragic land, then, of at least triple inheritance. His wilderness, in other words, is no escape from the travails of human history. He wrote of “That dark corrupt and bloody time while three separate people had tried to adjust not only to one another but to the new land which they had created and inherited too and must live in.” For Faulkner, not only do the facts of southern history prohibit any singular territorial claim by any one faction but the ecology of the wilderness also defies the very idea of sovereignty. This idea leads Faulkner to insist that we need a better theology to redress both humanity’s social and environmental sins: “[God] made the earth first and peopled it with dumb creatures, and then He created man to be His overseer on the earth and to hold suzerainty over the earth and the animals on it in His name, not to hold for himself and his descendants inviolable title forever, generation after generation, to the oblongs and squares of the earth, but to hold the earth mutual and intact in the communal anonymity of brotherhood, and all the fee He asked was pity and humility and sufferance and endurance and the sweat of his face for bread.”

In his popular story, “The Bear,” William Faulkner once described the wilderness of the South as having soils brutalized by whites and saturated by the blood of massacred Indians and beaten slaves, a tragic land, then, of at least triple inheritance. His wilderness, in other words, is no escape from the travails of human history. He wrote of “That dark corrupt and bloody time while three separate people had tried to adjust not only to one another but to the new land which they had created and inherited too and must live in.” For Faulkner, not only do the facts of southern history prohibit any singular territorial claim by any one faction but the ecology of the wilderness also defies the very idea of sovereignty. This idea leads Faulkner to insist that we need a better theology to redress both humanity’s social and environmental sins: “[God] made the earth first and peopled it with dumb creatures, and then He created man to be His overseer on the earth and to hold suzerainty over the earth and the animals on it in His name, not to hold for himself and his descendants inviolable title forever, generation after generation, to the oblongs and squares of the earth, but to hold the earth mutual and intact in the communal anonymity of brotherhood, and all the fee He asked was pity and humility and sufferance and endurance and the sweat of his face for bread.”

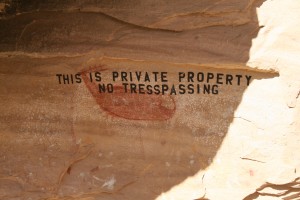

Although it might seem like a paradox, one reason we fail at building human community is that we are too human-centered in our view of the world. We aren’t allowing ourselves to experience the deepest of humiliations that nature offers—that discovery that our human concerns are superficial, temporary, and selfish. Instead of allowing ourselves to feel astonishment and vulnerability, we are often more willing to use land as a political football to play and win our games of identity than we are willing to do right by the land. If we are truly devoted to what is best for the land, we would abdicate our need to possess it, to own it, to believe it represents a continuation and affirmation of our own independence. We would instead be devoted to making it sharable across cultures and through generations. Giving ourselves to the common ground of our ecology in this kind of service would diminish the divisions that characterize Utah—divisions between the Wasatch Front and rural Utah, between Mormons and non-Mormons or Mormons and former Mormons, Democrats and Republicans, between classes and ethnicities, and even between state and federal government, between easterners and westerners.

A neighbor of mine once lamented to me that the hills behind our house were getting developed into homes, but it wasn’t because he craved the raw and wild qualities of the foothills. Those qualities were long gone by extensive mining before the houses ever arrived. What he craved was the license he enjoyed as a boy to ride a motorcycle in the hills with utter freedom outside the bounds of society; he craved the chance to be answerable to no one. What he perceived as a kind of childhood innocence struck me as willfully ignorant of a sense of responsibility to others and to the future.

It is only fair, then, to ask if pro-wilderness folks might be stung by a similar nostalgia, a nostalgia for living in a raw world of true solitude and wildness, untouched by the modern life we live and depend on and that got us to the wilderness in the first place. Nostalgia is a toxic emotion, one that rarely remembers history with any kind of accuracy and rarely achieves real change. What is sure to cure nostalgia is awareness of the history of the native populations that was not without conflict and violence, that the layers of history go back at least some 5000 years if not much more, and that we can no more sort through the crimes of history than we can count the blades of grass on the side of the mountains. Faulkner saw the dominion doctrine abused as an excuse for man “to hold for himself and his descendants inviolable title forever, generation after generation, to the oblongs and squares of the earth.” This kind of theology, which I fundamentally reject as both unchristian and even heretical, is what allows human beings to use land to draw lines between people and create enemies. But when we are beholden to the strangeness of nature and its sometimes foreign history and when we rise to the challenge of holding it “mutual and intact,” we are engaged in the very human responsibility to protect and restore ecological health for ourselves and for unknown future generations. Can you hear how Faulkner suggests that this requires not fierce loyalty to kin and clan but instead a sacrifice of such interests and an awareness of our mutual belonging to each other and to nature? We must seek the anonymity of brotherhood, we must welcome the dissolving of our differences in our mutual interest in the health of this land not only for our own children and posterity but for the posterity of all people and all the creatures upon it.

Faulkner suggests that we tend to be intolerant of wilderness for the same reasons we cannot tolerate the competing claims and histories of others: both mean having to recognize that we are not the completely autonomous and exceptional beings we like to think we are. And as he thematizes, our vengeful reaction to this unpleasant fact simultaneously destroys wilderness and reinforces social divisions. We will remain dangerous to nature, in other words, to the degree that we remain contentious, divided, and dangerous to each other.