Over the Paschal Triduum this year, if you recall, I read all four Gospels straight through. I had read the Gospels more than once before of course, but never all four of them straight in quick succession. If you haven’t done it I really recommend it, because a bunch of things shine through that you hadn’t noticed before. (For example, the thunderingly recurring theme of damnation really gave a cold shower to my flirtation with Universalism.)

One of the things that particularly struck me that’s relevant to my ongoing discussion with the great Sam Rocha is that in the Gospels, most people don’t follow Jesus because of his teachings. More often than not, his teachings make people balk and run away and no, it’s not “just the Pharisees” (Jn 6 is particularly striking on this), not that it would matter since one of the important themes is that we’re all “the Pharisees”. One thing that the Gospels come back to over and over and over again is that people followed Jesus because he healed them. Jesus would heal people, and then the crowds would follow him; and then he would teach them, and more often than not people were scandalized, but the reason people followed him was because he healed them. Even the apostles. Jesus healed Peter’s mother-in-law and Peter followed him, and by the grace of the Spirit Peter recognized Jesus as the Son of God, but it’s clear that until Easter morning he had no idea what that actually meant. “Yeshua” means “God saves” not “God teaches.”

If you’ve read me at all you know I care deeply about orthodoxy and theology. It’s about caritas in veritate, and both sides of that phrase matter a great deal. But the probably-apocryphal “preach the Gospel; with words if necessary” phrase has deep, deep wisdom. “If I do not have love…”

All of which brings me to Sam’s critique of the practical method. It’s a very interesting discussion in and of itself, particularly because it’s a discussion where we come down in favor of the same ideas–Sam and I both like Montessori a great deal–but for very different reasons. The fact that we can have this sort of debate is itself a very great thing.

My argument for Montessori stars with–does not end, but starts with, and views it as decisive–with “it. just. works.”

As I noted, and as Sam acknowledges, “it. just. works.” cannot be the end. There is no method that is not either implicitly or explicitly rooted in philosophical and even metaphysical assumptions, and those should be questioned.

Sam also lands a blow when he notes that “it. just. works.” can lead to stultification. Indeed, from the very self-understanding of Montessori as “the scientific method” (as opposed to “the Montessori method”), it cannot be a fixed method, once and for all. Dr. Montessori built her curriculum based on empirical experimentation, and that means it can change. Dr. Montessori was very affected by World War II and died shortly thereafter–if she had lived longer, the Montessori curriculum we now have would be different. The stewards of Montessori insist on not changing the method. I think that in practice this is salutary, because almost every “iteration” I’ve seen on Montessori makes it worse, not better. But this is nonetheless long-run unhealthy. For example, every Montessori educator I’ve encountered disparages electronics, computers and television. From Dr. Montessori’s writings about the wonders of the machine age and the man-machine symbiosis, I suspect that she would have a more nuanced view of computers as educational devices. That we cannot know, but “What would Montessori look like if Dr. Montessori had gotten started in the computer age?” is, I think, a very interesting question. But it is a question that can only be discovered through empirical investigation, not abstract thinking.

Indeed, as I wrote in my previous post, from the standpoint of the most orthodox Catholic Tradition, “it. just. works.” is and should be a decisive argument. From the standpoint of Catholic theology, God as the logos has a rational mind, or at least incorporates pure reason; He has inscribed His law in the Created Order, which is good; part of the Imago Dei embodied by man is a rational mind, and part of our vocation as image-bearing creatures is to use our rational faculties to understand the world we live in and thereby understand God. This makes “it. just. works.” decisive, precisely because from a Catholic perspective, “it. just. works.” can never be a coincidence. And “it. just. works.” cannot ever be summarized to testable results on metrics like literacy and math, although we cannot ever think of it as unimportant, but on broader metrics–as, indeed, Montessori does. And indeed it is not a coincidence that what Dr. Montessori found out about the child from her empirical investigation just happens to line up perfectly with what Catholic theological anthropology tells us about human nature. In the New Israel, the immanent is never far from the transcendent. This is, in the words of N.T. Wright, “Kingdom work.”

Politely, Sam hints, but does not quite say, that becoming a Montessorian can feel a little bit like joining a cult. There is a new worldview, in many ways diametrally opposed from the World. There is a particular language. There are strange rites. There is a subculture, and an insistence on doing things in a particular way, and a missionary urge combined with an anxious sense that the outsiders just don’t get it and that if they did, everything would be immeasurably better. You know what else is like that? Catholicism.

Of course, in Catholicism there is a both/and. Yes, submission is required, but it is never a blind submission; it is sincere submission through the education of conscience, which must be followed, by the grace of the Spirit. Faith and doubt are always in dialogue, we are born again every day. Just like Montessori frozen in amber is not, ultimately, true Montessori.

I’m going to go back to themes that I’ve broached before. A great Catholic hospital is, yes, a hospital which is not just a hospital, it is a hospital that is about souls. But a great Catholic hospital is also one that actually heals your broken arm. Good medicine–scientific medicine–is not the end, but it is the beginning. That step cannot be skipped. We should take it for granted that a Catholic hospital which does not take scientific medicine is anti-Catholic just as much as we take it for granted that a hospital that performs abortions as anti-Catholic.

There are many things which are astonishing about the cathedrals the Church built; not least among them is the fact that they stand. The world’s most beautiful cathedral is useless if it does not stand.

The Church is not, or should not be, a social club where we hang out and have all of these fascinating intellectual debates, and maybe even runs soup kitchens. The Church is an Army. When you join the Marine Corps, you don’t sign up on a dotted line and then go on with your life the way it used to be. You’re grabbed by the collar and dragged into this great big machine which breaks you down and then builds you back up and you come out of its giant digestive tract a new man. There are all these strange and unfamiliar rules which must be obeyed even though they don’t seem to make sense. These rules have theoretical, philosophical, and even theological underpinnings, and these can and should be discussed by the people whose job is to discuss them. But the ultimate metric by which those rules are judged is do they lead to victory in the battlefield, which is perhaps the starkest empirical test.

The Church has a job to do. This job is to produce saints. The master gave his steward a lot of talents, and now he expects a return on his investment. He does not expect a long, fascinating, true even, speech about the nature of investment. He expects results. To produce these results we do have to think and theologize and philosophize. Again, this is the Catholic Thing; both/and. But ultimately we will be told–or not–“Well done thou good and faithful servant.”

One of Sam’s preoccupations–a very true one and a very important one–is that we not confuse “education” and “schooling.” Thankfully, neither does Montessori. Yes, the Montessori curriculum takes place in a classroom. But once you see the world through a Montessori lens, it carries over everything you do as a parent and educator. Montessori is not just a classroom (just read Montessori blogs–no, really, do). My daughter starts Montessori school in the Fall, but she’s already a Montessori child. Catholic education must not be just about what goes on in a classroom, whether it is a school classroom or a catechesis classroom. Catholic education must start with educating parents.

Here’s a final point about method: the Church is a big, big animal. One beeeeellion people. More, in fact. And growing at an astonishing rate. And most of the people the Church has to educate (inside and outside the classroom), as Sam well knows, do not live in the kind of comfortable Western world we do. The Church is meant to embrace the entire world. And you cannot do that without methods, because only methods scale. And scaling is a holy duty.

The rosary is a method. The Liturgy of the Hours is a method. The Spiritual Exercises are a method. The liturgy itself is a method. The liturgical calendar is a method. The sacraments are a method. Growth in virtue and holiness is (or, rather, should be) a method. The Rule of Benedict is a method. The first monks went into the desert without a method, under the Spirit, and they were saints. But monasticism scaled because it put together a method–very much joining empiricism and theology in its elaboration. And because monasticism had a method, it could scale, and because it scaled, monasticism saved Western civilization and rebuilt it and magnified it, and produced countless saints. Method without the Spirit; method without questioning, is no method at all (as the history of monasticism also shows). Catholicism is wealthy because of its methods–just ask a low-church Protestant convert some time. The problem with education in the Church is that it does not have a method. It has plenty of good intentions, and plenty of good people, and plenty of talented thinkers, but what it doesn’t have is a method. And it is because it does not have a method that it either copies the secular world or just muddles through. Catholic teachers in Congo, and harried Catholic parents in Peoria, do not have time to be theologians and philosophers, and the Church fails them if it expects them to do all the intellectual spadework and reinvent the wheel. The work ahead is massive. We have to light the world on fire with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Montessori is a method. Catechesis of the Good Shepherd is a method. It is a method that scales. It is a method faithful to Catholic Tradition. It is a method that works. These aspects cannot, must not be ignored.

If I was named the Church’s Minister of Education tomorrow (hint, hint, @Pontifex!), would Catholic education twenty years from now look like what Montessori looks like today? Almost certainly not. But would we start with Montessori? Absolutely, yes. Why? Because it is a method that works. From an orthodox Catholic perspective, that is absolutely a good place to start; in fact, the place to start.

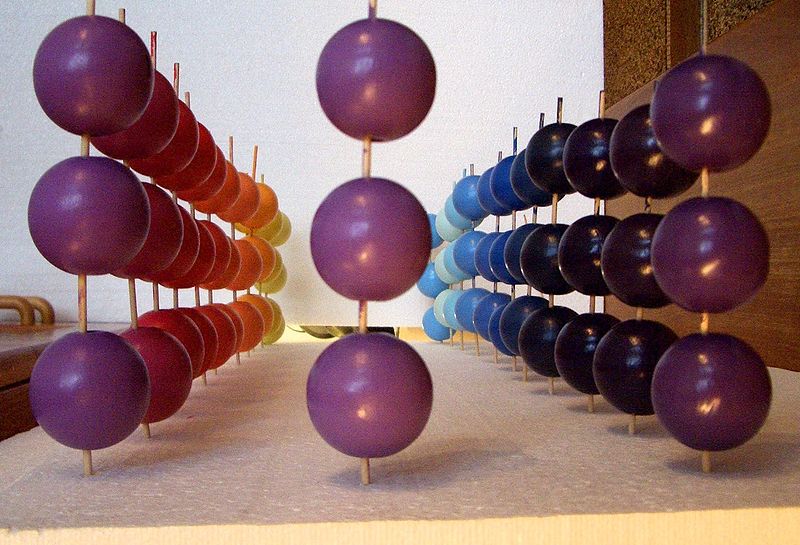

“Montessori Kugeln“. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.