Christianity is “a set of contradictions held together by grace.” The history of orthodoxy is the history of trying to hold together, and even of sharpening, seemingly contradictory truths of faith; the history of heresy, meanwhile, is the history of trying to resolve those seeming contradictions by overemphasizing one pole at the extent of the other. Thus, the Scriptures describe Jesus as both man and God; heresies have overemphasized one at the expense of the other; orthodoxy proclaims that Jesus is both fully man and fully God.

Heresy therefore always poses a tricky double challenge for orthodoxy: a heresy that affirms a thing that orthodoxy also affirms (albeit to the exclusion of other necessary truths, or drawing false consequences from it), by definition, cannot be wholly evil, and orthodoxy must affirm the good things in it; and there is always a temptation to face the overemphasis on one pole by overemphasizing the other pole and falling into the other heresy (whether formally or in practice).

It is this latter tendency that worries me when I see certain Christian discourses about Modernity.

For example, there is a certain critique of “individualism” that rejects the very notion of the importance of the individual. Historically, this is what Christianity burst into the world stage proclaiming. Christianity proclaimed that God had created Adam in order that Man be God’s viceroy over Creation, and that God held human nature of such importance that he freely chose to take it on. Man, in the traditional understanding of human nature, is destined for divinization, godhood.

David Bentley Hart relates how this “total humanism”, the belief in the infinite value of every single human life, was the totally new thing that Christianity brought to the world, and how the Christological debates of the first eight centuries of humanity provoked the greatest men of the age to engage in a sustained, powerful, unprecedented reflection on what, exactly, it means to be a human being. Christianity’s lofty vision of the individual, pinnacle of God’s good creation, and his divine destiny, was in marked contrast with a Pagan social order that saw man’s worth as dependent upon his social station.

Even though it’s a tired and hoary cliché, it’s not without reason that some people describe Augustine as “the first Modern man”, with the deep introspection and subjectivity of a work like the Confessions–to an extent that would have seemed, frankly, obscene, to many of his contemporaries.

This sustained attention, even glorification, of the individual, very much including his subjectivity, is historically a product of Christianity.

Is it really a surprise that a Messiah who said that following him could involve disowning your own family, called for setting the world on fire and, indeed, who showed that following him could involve a direct and deadly confrontation with the legitimate political and religious authorities, would, once revealed to be the Son of God, create a cultural climate friendly to individual subversion of earthly authorities and traditions?

Now, of course, Modernity can take this individualism too far. A pure expression of subjectivity unrelated to a relationship with some objective Good is, in the end, nothing but solipsism, and can all-too easily dissolve into a dangerous nihilism.

But it seems to me that many discourses that combat not just excesses of Modern individualism but individualism writ large run the risk of falling into the opposite, and equally erroneous, heresy. There are many practical reasons for respect for things like community and small-t tradition, and we should take them seriously. But prudentially wise though this may be, where it finds purchase in the Gospel I do not know.

Similarly, Modernity’s skepticism of government power finds its ultimate root in the Gospel. Bishop Ambrose of Milan could exclude the Roman emperor from communion and demand that he repent of crimes committed before entering his cathedral, just like the Pope made the German emperor take on the penitent’s robe at Canossa. The contrast with the Pagan Roman Empire, where the Roman emperor was held to be a divine being (and before that, Egypt’s Pharaoh), could not be starker: political authorities, though legitimate, are nonetheless bound by divine law and the judge of this divine law is the Church. And, of course, the separation of Church and State also finds its ultimate root in the Gospel.

The belief in the infinite dignity of human beings and the submission of human governments to divine law–and the fundamental equality of all human beings–could only naturally lead to the understanding that each human being, at the very least, in his relation towards the state, is endowed with inalienable rights.

By the same token, once Christianity burst unto the world stage proclaiming the–to Pagan ears, incredible–equal dignity in Christ of men and women, something like what we call feminism became inevitable. The medical realities of childbearing and the technological and socioeconomic realities of agrarian society dictated a patriarchal social order with women’s roles confined to the domestic. The clash with the defiantly implausible Gospel, no matter how long delayed, was inevitable. The apostles caused scandal by traveling with women ministers (bracketing the question of what type of ministry, exactly, it was), and the countercultural prominence of women in the early Christian communities is well attested historically. As social phenomena, the parallel between patriarchy and slavery seems clear: because socioeconomic realities made these institutions seem unavoidable, the Church (to our continuing shame) tolerated them even as it chafed at their yoke and, sometimes in spite of itself, developed a critique that spelled their eventual doom.

So too Modern empiricism finds it roots in a Christian understanding of the natural world as divinely ordained by a God who is also the rational logos, given to a man endowed with a rational nature as part of his divine image for him to rule as steward. The world is “disenchanted” in the sense that animist-like natural forces cannot be said to have any existence in and of themselves, but are only, at best, derivations of the One God’s sole power (or demonic forces). Animist and Pagan quasi-pantheisms become impossible, the world becomes legible and dominable. Descartes’ view of man as “a kind of master and owner of nature” is sometimes portrayed as a tragic departure from Christianity to something novel and drastically different, but how this differs from the Adamic vocation to rulership over Creation I am not sure.

While we are very understandably and very healthfully allergic to utopian versions of the myth of Progress, we must nevertheless understand that a metaphysic of human time as an arrow, launched by Providence, directed towards a better future, is also a Christian innovation. The Christian Bible will have none of the Greeks’ Golden Age: the Heavenly Jerusalem described in Revelation will be better than the Garden of Eden. Furthermore, the Resurrection of Jesus Christ with a glorious body means that the Kingdom of God is a reality in the here and now. The Kingdom of God is not, or not only, some eschatological future. New Creation has been inaugurated in the flesh of the Risen Christ, and the mission of the Church, which is his body, is to make Jesus’ reign a reality in the here and now. The early Christians did not have the quasi-Gnostic yearning of the Pietist for some disembodied Heaven where the chosen few would be lifted out of this vale of tears into a different spiritual plane; rather they announced the reality of the inauguration of the Kingdom of God and the New Creation in the glorious Body of the Risen Christ, and worked to fulfill the Adamic vocation, now fulfilled in Christ, of ruling over and divinizing God’s good Creation.

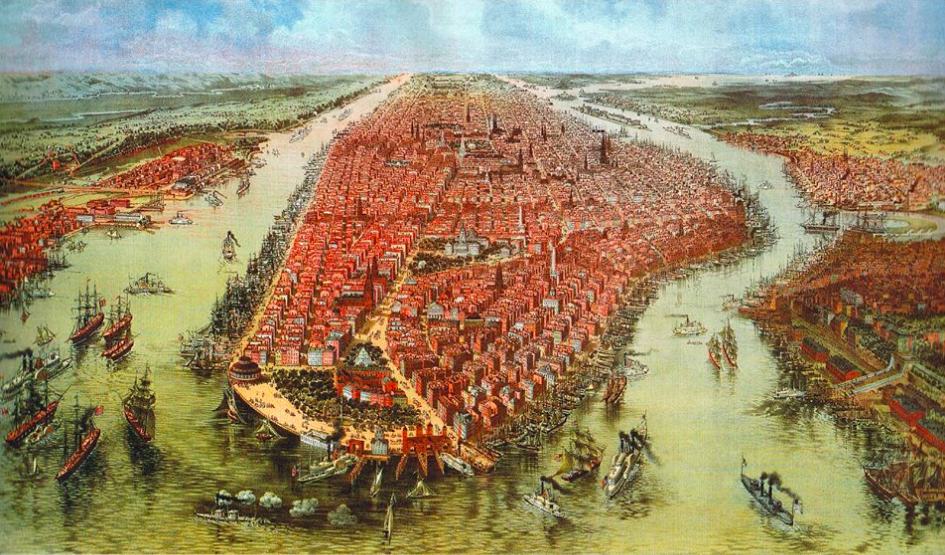

Casually repudiating pre-Christian notions of time as an endlessly repeating cycle, Christianity boasts of a before and an after, with the after being decisively better than the before. The orthodox understanding of Tradition, uniquely preserved by the Roman Catholic Church, is that of a growing understanding of the unchanging deposit of faith by the Church. The Apostles, then the Fathers and the first Eight Councils, then the Schoolmen, the Franciscans, then the Carmelite Doctors, then the Neo-Thomist and Patristic ressourcements, these together constitute progress. Furthermore–again–this progress cannot be only intellectual. Once it had the clout to be able to do so, the Church reformed the laws of the Roman Empire.

The great monks of the West who saved Western Civilization did not just produce books, they produced technology. As Hart writes, “[w]e may find it somewhat difficult now to appreciate the revolutionary implications of devices like the heavy saddle with stirrups, the wheeled plow, the rigid horse collar, heavy armor, and the nailed horseshoe, but they allowed for the cultivation of soils that had never previously been genuinely arable, helped initiate a long period of Wester military security, and did much to foster the kind of economic and demographic growth for want of which the Western Roman Empire had fallen into ruin.” No culture before the Western medievals, largely led by monasteries, “had ever boasted technological advances of such scope and variety.”

Modernity’s problem with Utopia is not ambition in the service of social progress, which was as much present among the Christian Abolitionists as among the Atheist Eugenicists. The problem is a combination of the forgetting of the other truths of Christianity, of the forgetting that Utopia can only be reached asymptotically, and of the use of state coercion in the service of the pursuit of Utopia. Note that many iterations of Christianity have also been problematic in the use of state power at the service of dubious ends. Meanwhile, our Adamic vocation is to act as king, priests and prophets in order to divinize this world, which is a temple erected to the glory of God. While we are very keenly aware that original sin means Utopia is impossible, we don’t seem to be as much aware that it equally means that the present situation can be improved. Immanentizing the Eschaton is impossible, but eschatonizing the immanent is a duty.

Perhaps the greatest utopian of the 20th century was John Paul II. What is more utopian than the vision of the Gospel of Life, whereby not only the law, but the economy, society, and culture, all join together in the welcoming and flourishing of all human life, resplendent of its divinity, at every stage? What is less pietist and gnostic than a theology of the body that invites all of us to recognize ourselves as a body and put this body at the service of our divine vocation, and the fundamental equality in dignity of men and women? What is more ambitious than a social doctrine which combines economic initiative, private ownership and mutual aid and solidarity in the service of the economic and social flourishing of all? What was more utopian than the impossible-until-it-happened drive to bring down the Soviet Empire, lock, stock and barrel?

All these things that Modernity affirms, Christianity ought alike to affirm. As Justin Martyr wrote, anything good done by anyone belongs by rights to the Church Catholic, since all good comes from God. Modernity, then, goes astray when it forgets its Christian roots, when it lets its anthropology be flattened by atheism or deism, when its utopianism becomes too utopian. Christianity’s role in relation to Modernity, then, is, first, to recognize her daughter, and then, rather than seek to oppose her wholesale or destroy her, bring her back into the family, like the Prodigal Son, and restore her to her fullness–which is also that of Christianity.

This analogy also points to something else. A child defines herself primarily in imitation of her parents. And adolescence is the process by which the child defines herself in contrast to her parents. This is a healthy process, enabling a child to grow into an independent adult. But what all too often happens is that as the child grows into a rebellious teenager, instead of channeling the rebellious energy towards the construction of the healthy adult (not an easy task, to be sure), the parent meets each act of differentiation with equal and opposite force. And typically, this behavior only serves to worsen and radicalize the rebellion of the teenager, and to deepen the fissures between the parent and the child. Very often, one finds that if the parent had listened more carefully to the child, a lot of bad blood might have been avoided–and we also very often find that the parent and teenager, even as they reject and antagonize each other are, from the outside perspective, like mirror images of each other.