Since I’m on a Balthasarian kick these days, it’s impossible not to talk about the idea of theological aesthetics.

Much of Balthasar’s thought springs from the idea of the Beautiful as the “forgotten transcendental.” Think of the three Great Transcendentals of classical Greek philosophy: the True, the Good and the Beautiful. Both theology and philosophy place great emphasis on the first two and tend to overlook the third. Balthasar’s idea in writing a Theodramatik was precisely to give the Beautiful pride of place in our understanding of God. (In turn, this understanding of God as the Beautiful was important for the Fathers and remains important in Eastern Christianity, so this is part of the broader ressourcement of which Balthasar was such a key figure.)

There’s something very seductive about this idea. But not in the best way. A lot of theology, I fear (am I projecting?), like a lot of thinking, is driven by the drive to say something new; for orthodox theologians, this is made tricky by the necessity not to speculate “too far.” The idea of rereading theology through the lens of the Beautiful, then, is very seductive as a new “spin” to give on theology, without risking heretical speculation.

To this, I might bring in Balthasar’s sparring partner Karl Barth. The simplicity of Evangelical ecclesiology gives theology a very clear role: the Church’s job is simply to preach the Gospel; and Barth is clear: theology’s job is simply to be an aid to preaching. This has the very great virtue of making theology what I think it should be, which is a handmaid. What actually matters is to preach the Gospel, and theology is only there as a tool that makes that easier.

I had a friend in high school whose father was a very accomplished professional jazz guitarist. When he was a kid, my friend asked his father to teach him the guitar. “Sure, I’d love to,” my friend’s father told his son, “but first I want you to learn how to read sheet music, as well as the main chords and the basics of music theory.” Since my friend was a wiseass, he responded: “Well, Paul McCartney never learned any of that, and he seems to be doing fine.” And since my friend’s father was wise, he responded: “Yeah, but you’re not Paul McCartney.”

When St Francis founded his Order, he wanted to ban theology, and the teaching of theology, from the Franciscan family. It was just a distraction from preaching the Gospel and serving the poor. By the grace of God, Francis changed his mind–and if he hadn’t, it’s certain nobody today would know who he was. Francis was Paul McCartney. Most of us, Francis realized, aren’t. And because Francis changed his mind, we have two of the greatest Doctors in history, Anthony of Padua and Bonaventure.

All of Creation is a great big symphony, and we all have our part in the orchestra. Music theory is important, and necessary, and even wondrous–but the point of learning music theory is to make music. The two Great Commandments, and the Great Commission, are about doing things. I do think it is an important (the most important?) test of theology that it “cashes out as” (in one way or another, no matter how indirectly) Kingdom-work.

This was what was in the back of my mind when I added to Balthasar’s call for a “kneeling theology” a call for a “working” theology.

You might say that when it comes to the Transcendentals, I’m on Team Good. And maybe I am. It would be a caricature, but part of me wants to say that of the three Transcendentals, Western Tradition has emphasized the True, Eastern Tradition has emphasized the Beautiful–but the Gospel emphasizes the Good. I might even go as far as to say that the true “forgotten Transcendental” is the Good. Not because we don’t talk about it; we do; a lot. But very often we talk about it on the way to something else.

The Truth and the Beautiful are things we contemplate. But the Good is something we do.

It is about caritas in veritate, not veritas in caritate.

The God that we can derive from metaphysics, the prime mover, the uncaused cause, the Neoplatonist One, is (to me) almost impossible to imagine not sitting there, in the plenitude of his (its? her?) fullness of being and transcendence. This is not the God of the Bible (not that the true God does not have the attributes that metaphysics tells us any God must have; not that the metaphysical approach is wholly worthless). The God of the Bible is the hunter, relentless, never giving up, going beyond every limit to redeem his Creation. The economy of the Trinity is one of movement and action, the Father generating the Son and the Son responding, in the procession of the Spirit. God is actus purus. Creation is action, but moreover, the entire Christian love story, God’s self-revelation in Jesus Christ, is an action, an action that demands re-action.

Even the one with a purely contemplative vocation, in Saint Benedict’s great motto, must work.

How do we prevent theology from becoming a pietism for the intellectual? By calling it back to its vocation as a servant of the work of the Church. And does not a primarily aesthetic theology take a risk of distracting us from that goal?

Nonetheless… Nonetheless nonetheless nonetheless… (I swear, I’m not trying to do a dialectic.)

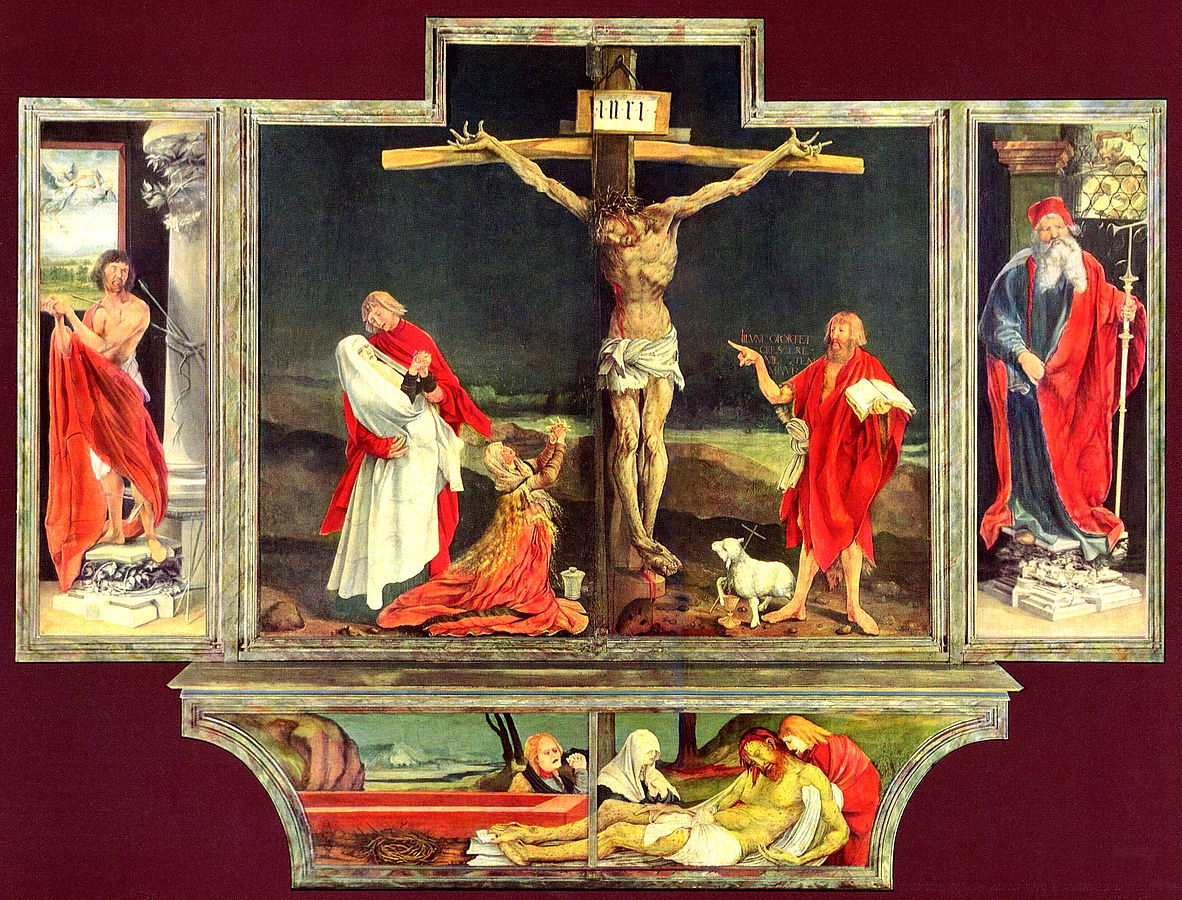

Is it not also true that a de-emphasizing of the Beautiful is one of the most depressing features of Modernity? Don’t we live in a world starved for beauty? To put the point more sharply, is not the totalitarian phenomenon to be understood at least in part as a reaction against Modernity’s de-aesthetization of the world and an attempt at re-aesthetizing it? And if so, is it not incumbent on the Church to provide a counter-program of re-aesthetization of the world so as to save Modernity from itself? And if the meaning of creaturely life, like the Son’s, is fundamentally eucharistic, and if the Eucharist is the “source and summit of all Christian life”, and if one of the ways the liturgy is the liturgy is to allow us to approach God through the Beautiful, then must not the Beautiful have a central place in our theology?

(Those are rhetorical questions. The answer is yes.)

Furthermore, is not one of our key pitfalls a theology of reciprocity, one where things are done and believed in order that something else may be accomplished? Are we not in need of ceaselessly reminding ourselves that the character of God is one of ontological generosity, unlike us sinful arch-apes who, without grace, only ever do things expecting something else in return? And if so, is not Beauty a great reminder of God’s ontological generosity? Is not the appeal of Beauty precisely that it is its own self-justification, that it serves no other purpose than itself, that it is, in and of itself and by itself, a permanent reminder of God’s permanent generosity, and of the sheer givenness and gratuity of all that exists? And, therefore, are we not then obliged to never regard Beauty as something incidental, as something extra, but on the contrary precisely because of its gratuity as something essential?

As you can tell, I have a lot more reading, and kneeling, and working to do.