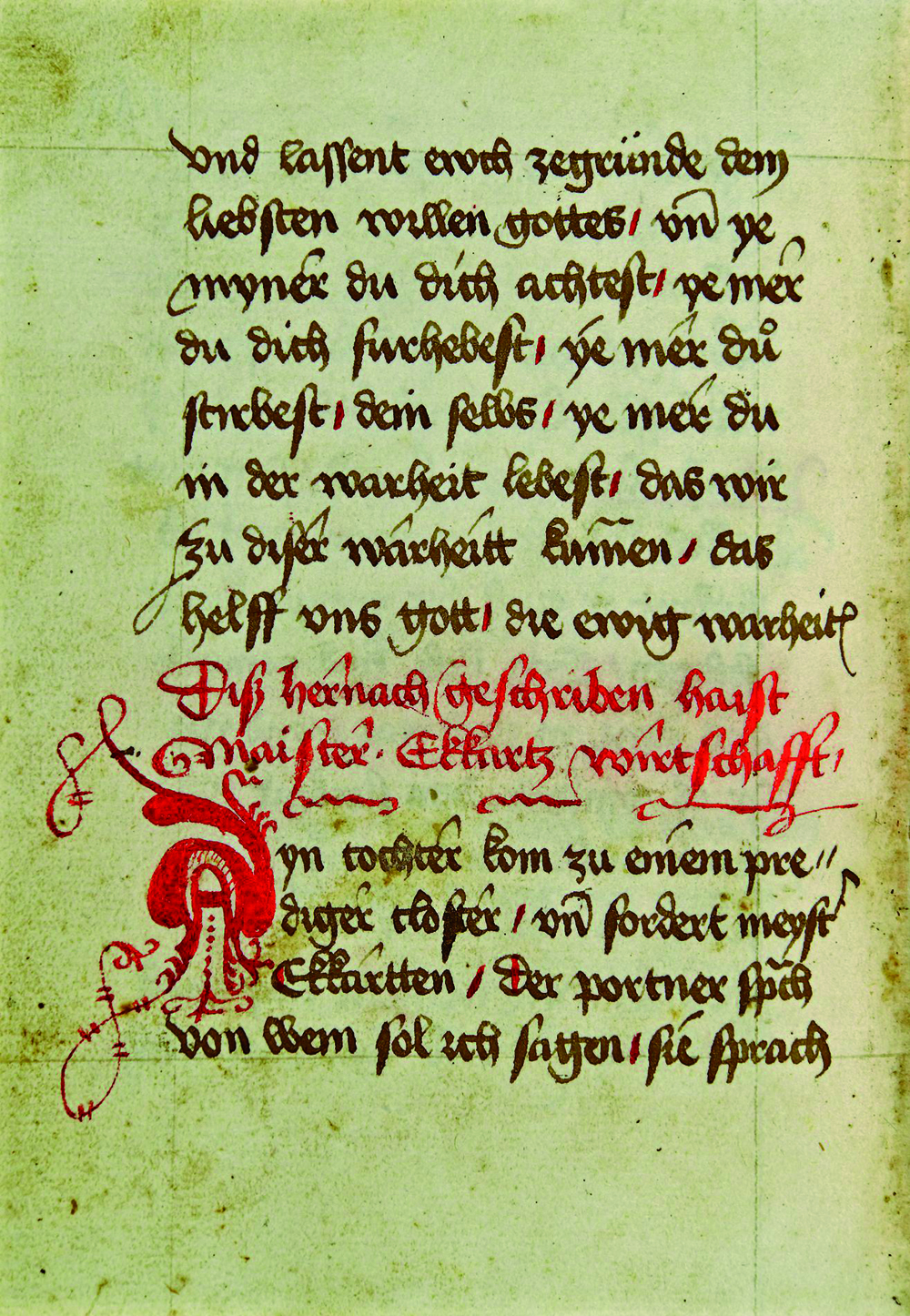

These days I am reading an anthology of sermons of Meister Eckhart. They’re wonderful.

One of the things that I’m constantly struck by is their traditionality. By this I mean not that they propound or expound traditional doctrines, or that they’re written in a traditional “style”, but rather that the way they are written represents the best of the Catholic Tradition.

These are sermons; Eckhart is expounding the readings of the particular day where he is preaching. And the way he does it is reflective of the best traditions of the Church; an instance of the Church’s Tradition, which is the life of the Spirit within the Church.

Here’s what I mean.

1. The easy fellowship with the spiritual senses of Scripture.

Tradition distinguishes between two senses of Scripture: the literal–the sense intended by the human author–and the spiritual sense–the manifold senses intended by the divine author. The Protestant Reformation was in many ways a rebellion of the literal sense against the spiritual sense (never mind that they didn’t understand the literal sense either), but the Scriptures are incomprehensible without the spiritual sense (for example, nobody until Christians came along thought that the story of Adam and Eve had something to do with a thing called original sin; and Jesus himself informs us that all the Hebrew Scriptures have an implicit christological sense).

Now, the literal sense is very important, and in many ways can help to illumine the spiritual sense (as well as the spirit of the reader).

But we live in a very literalistic age. Cultured despisers of Christianity obsess over whether one can cross a sea barefoot, or whether the prophet Daniel believed that at some point in the future a person would fly down from the sky on a literal cloud. Things can just have their surface meaning, and no more. A thing either is, or is not.

And scriptural exegesis sometimes lets itself be infected by this spirit of the age. Again, this can be beneficial, such as when it explains the sense a parable would have for its 1st century hearers; very often this reminds us of the very Judaic character of Christianity, and the dense links between the New Testament and the Old; or it reminds us of the socially subversive aspects of Jesus’ ministry.

Okay. But it’s still very refreshing, and very invigorating, to see Eckhart have a sort of easy-going contempt for the literal meaning of Scripture. When he expounds the story of the raising of the son of the widow of Nain, Eckhart plucks out this phrase: “he approached the gate of the city”, and declares: “the city is the human soul”–and off he goes, preaching about the soul, and how when Jesus approaches our soul, we are raised.

Here we see the great beauty of Medieval (and Patristic) Catholicism, which made the Scriptures so familiar, so bone-deep, that there is a perfect facility with the text, with its countless layers of meaning, with its many-colored splendor, in this prelapsarian time before the Reformation ogre came and flattened the Scriptures for most of Western Christianity. It is this same deep and easy fellowship with Scripture that we see in the great Church Fathers (especially Pseudo-Dionysius the Aeropagite, whom Eckhart admired so much).

2. The close link between Scripture and Tradition

Almost invariably, whenever Eckart cites a verse of Scripture, he follows it up immediately with a citation from a Church Father. It’s like it’s impossible for him to read Scripture apart from the Heart of the Church. The Bible cannot be read “alone.” It only comes alive where and whence it was received and is given, which is the Heart of the Church. The Tradition of the Church is like a great symphony, within which Scripture is one of the great themes, but which only comes alive with the support, and gloss, and vibrancy of the other themes. God does not write monophony.

The Fathers bring alive the spiritual senses of Scripture, both through the necessary restraint on the total speculation that the recognition of the spiritual senses opens up, and through their bringing forth of the many spiritual senses.

Eckhart doesn’t think he knows Scripture unless he knows it through the Heart of the Tradition, and shows us how to be Bible-believing Christians.

3. The voracity for knowledge

Another great thing about Eckhart’s sermons is how intellectually voracious they are. He is always citing Aristotle, Maimonides, Averroes, scientists, and others. It wasn’t just Aquinas–this is the grand sweep of the Church’s Tradition, to “take every thought prisoner and make it obey the Messiah.” The Church Fathers despoiled Greek philosophy of its useful concepts, without letting its non-Christian elements corrupt their theology.

Catholicism believes in reason; it believes in philosophy. The Protestant view of “Bible alone” and the Lutheran view that the depravity of sin has made natural reason uselessly fallible makes it heroically difficult for faith not to devolve into a biblicist fideism, whether fundamentalist, existentialist or liberal. Instead, Catholicism holds fiercely onto the Biblical view that the one through whom everything was made is the Logos, the Wisdom of God, such that, as Aquinas put it, “all knowledge is in principle noble”, and such that true faith can only exist on a solid bedrock of reason.

Whatsoever things are good, make use of them.

Again, when I read those sermons, I can only come up with the concept of the symphony to describe them: the manifold senses of Scripture, the light of Tradition, and the light of natural revelation, all of these come together in a great symphonic unity, with many instruments and many themes highlighting each other, building on each other, dialoguing with each other. This is the song of Holy Tradition; this is the wings on which man ascends towards God.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.