Forget about history, philosophy and theology for a moment.

Think instead about people’s basic, social, everyday commonsense experience.

I step outside my front door, and I see cars. I see tall buildings. I see concrete. I have been on planes. I have been in hospitals, waiting in anxiety on a medical doctor’s judgement. I have seen loved ones receive routine treatments for ailments that would have killed them a hundred years ago. My home has heating, running water, electricity, the internet. My main problem with regard to food is trying not to get too fat. I have seen video streamed live from space.

The reason why all these things are true is because the scientific revolution happened. “Science”–I am speaking extremely generally, here–has accomplished an enormous amount. When I put my family on a plane, I am trusting science with my life and the life of those whom I love most dearly to accomplish the nearly-unthinkable feat of very reliably lifting and maintaining hundreds of tons of steel into the air at tremendous speeds. And I don’t think even twice about it. That’s how much I trust “science.”

And “science” hasn’t found evidence of God. Nevermind that it’s outside its epistemological remit–I am talking about basic, common sense experience of every day people. Science hasn’t found evidence of God, and it works just as well without the God hypothesis. And science just works. It just works, man! I flip on the light switch, and light comes on. I am writing this on a computer connected to the internet. All that stuff works. Science makes these incredible claims, and it just delivers on them, man. And while I may know that science may not require or indeed even be compatible with a doctrinaire materialism, it certainly has a tendency to lead the only-casually-thinking mind more towards immanentism than towards (say) platonism.

Now, what about Christianity? Well, it makes claims about God, and about the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, but those are pretty remote from my everyday experience. Not everyone walks around with a mystical awareness of the presence of God in them; not everyone has the time to read The Resurrection of the Son of God and Jesus and the Eyewitnesses.

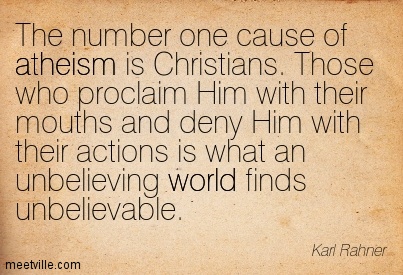

How else could I know Christianity is true, at the everyday experience level? Well, the Gospel of John gives me a standard by which to judge that: “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.”

Is the supererogatory love of Christians really that obvious? Am I bombarded by evidence the holiness of Christians and of the Holy Spirit in the same way that I am bombarded, all day, every day, everywhere I look, by the evidence of the world-bestriding success of science?

People, yes, do form beliefs on the basis of reason, and grace. But people also form beliefs on the basis of the cumulative impact of countless experiences, of the sort of “background noise” of life that gives rise to particular inclinations of common sense that make some worldviews seem more plausible than others, some more attractive than others.

Just like evidence for “science” is not just in a lecture on physics but in the fact that nobody even thinks about it when they turn on the light, the evidence for “Christianity” is not just in the Gospels and the cosmological argument, it is also in, well, actually existing Christianity. Christianity is made plausible–perhaps more than anything else–when people see in Christians the manifestation of something, well, otherworldly, something so extraordinary that it begs for a supernatural explanation. Are we really delivering on that promise? On that divine command?

Science said it can put a man on the Moon. Christianity said it could make men Christlike. Who has the better track record?

This, this, is our real challenge in apologetics. And increasingly, I fear that much of the work that is being done in apologetics and perhaps even theology generally is meant to distract us from this much more fundamental, much more arduous problem.