Recently, a student, who has taken multiple courses from me, told me that when evangelical students take my courses they assume I’m an atheist. In fact, in my graduate student orientation this week, a student said the same thing to me, “You sound like an atheist.”

Now it’s true I teach comparative religion at a “secular” university. Our university was sued when the college first tried to bring religious studies into the curriculum. So, in part, to appease these concerns, they put comparative religion into the school of international studies and they promised that they would not teach theology, but only teach about religion. Now, for me, this was a fortunate decision all around.

I love teaching religion in a school of international studies because religion is ever relevant not only for present day political conflicts but also to understand the wide stretch of world history. I also like studying religion as a cultural phenomenon. It makes me move around various faith systems like they are precious, foreign objects that must be treated with respect but also with an intense radically empirical perspective. This perspective, as William James said so well, must comprehend a “full fact.” This full fact involves “A conscious field plus its object as felt or thought of plus an attitude towards the object plus the sense of a self to whom the attitude belongs….”

James did not have the European attitude (read Durkheim and Weber) that one’s personal perspective was somehow an illegitimate aspect of one’s study. In fact, I often tell students, as a bow to the school of hermeneutics, that the heart of education is to test one’s pre-understandings or prejudices toward an object as one studies that object. And, of course, that object may be a subject, a “living human document.” This is the case in my own radically empirical sociological perspective. I study people being Christian, how they feel, act and organize themselves in relation to the objects that they worship and love.

But I still wonder whether I should be more upfront about my own religious inclinations. I’ve been teaching for more than a decade at my university and I’m well established and secure. I’ve recently thought, “Well, why not say who I am and then go ahead and teach as I always have using methods and theories from relevant scholars in the study of religion?”

But I still wonder whether I should be more upfront about my own religious inclinations. I’ve been teaching for more than a decade at my university and I’m well established and secure. I’ve recently thought, “Well, why not say who I am and then go ahead and teach as I always have using methods and theories from relevant scholars in the study of religion?”

But what rings in my ear is Max Weber’s tortured and authoritative voice. If you have not read Weber’s “Science as a Vocation,” you must. As he says, the spirit of our times is the “disenchantment of the world,” and if one cannot make that “intellectual sacrifice… then the arms of the old churches are opened widely… after all they do not make it hard….” Weber takes no prisoners, science demands disenchantment and this means, for him, the assumption that culture is a human construction, including religion. At times, I find this kind of analysis stultifying and even deceptive or deceiving. Like I said, James argued that we must include our own perspective in what one is studying.

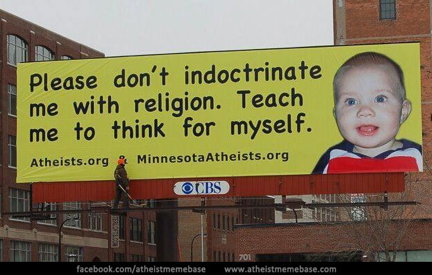

And yet, as someone else told me, “No, don’t say anything. You challenge them to think for themselves by forcing them to make up their own minds, regardless of what you think.” Some walk away from my class actually hating me for my “objectivity” and my unwillingness to share my religious perspective. Perhaps this is the price that one pays. But I remain somewhat dubious that this is my “duty.”

Still other religious scholars would say, “It makes no difference what your personal religious inclinations are, just do your work.” And I think they are right to a point. But I wonder if today’s students are different. To be sure, students today can track down a professor’s biographical record and find out where she or he stands on issues. But they also seem to need to know where the teacher is personally, or at least it seems to me. This helps them decide whether the teacher can be trusted.

Plus, and this may be most important, it shows them that as a “believer” one can stand outside oneself and examine a religion from an outsider perspective. That is, there is nothing to fear to look at Christianity, my own religion, from a Marxist, psychoanalytic, or sociological perspective. These are all simply viewpoints that may or may not reveal and illumine aspects of a religion that might otherwise be hidden from view when only looking at religion as a believer or insider.

Sometimes when I teach Western Religions (I realize a misnomer, I didn’t choose the name), in which we study Judaism, Christianity and Islam, I begin by arguing that each religion exhibits a distinct construction of God. Students occasionally gasp, “Constructions of God, aren’t these given by God?”

And I say, I don’t think so. The constructions are just that, attempts to read ancient texts and sketch pictures of God that are offered, often in quite diverse ways within these texts, in each of these traditions. And so I argue that these religions are just that, approximations of what humans have thought, imagined and experienced in light of their experiences with this “ultimate reality.” And, of course, as to how close these constructions are to “God” remains debatable and interesting but in the end a matter of faith.

My thinking also echoes my favorite University of Chicago teacher, Jonathan Z. Smith. Smith argued, “Religions are forms of human creativity.” Creativity is the quintessential human capacity, to make something new from the forms and thoughts that we are given.

So, maybe just maybe, by saying that I’m religious and showing that religion is human creativity in action, it frees students to think critically, and frees them to see its beauty and its problems. I sense that if people are free than they will discover what is true about religions for themselves.

These are my immediate conclusions. I really haven’t made up my mind. I begin teaching Thursday. I’m wondering what you all think?