I asked my Jackson School International Studies class called, “Cultural Interactions in an Interdependent World,” to give their tribal descriptions and share them with each other. The results, from 200+ student versions, were breath-taking. I can’t disclose those, but I do offer you my own below. I suppose, I would wonder in return, what is your tribe?

I grew up unaware of my race or ethnicity, and with the privilege of being a white male in America, an objective observer, a strange, opaque blank spot on the page. The unmarked group. We didn’t self-identify; no one really thought about it much, other than, white bread Bellevue boy—at once an invisible mark and at the same time, the most powerful position in the world—a white male with the world at his feet.

But then, into my upper middle class neighborhood, two black families moved in, an NBA basketball family, and a President of a Community College. The teens from each family joined our neighborhood gang. Yes, we called ourselves a gang. We talked and became friends.  I read Black Like Me in Junior High; I observed but barely noticed the Civil Rights movement on TV. And I thought—I have friends who are black. I like them. In school, we ‘studied’ Native peoples, and I was fascinated, but there was no Native near me, they were strangely blank too, but their stories, their lives, intrigued me. But of course, we lived on their land. Where are they? Natives, for us, were pictured in popular culture as a part of the natural world—a world that was frozen in time—but in my world, in the 1960’s we could not swim in Lake Washington because there was too much of our shit in the water—and even more alarming, Lake Erie was literally catching on fire—something was very wrong. A popular commercial on TV was an “apparent” native person* looking at a pile of litter, and a tear coming down his face—us white

I read Black Like Me in Junior High; I observed but barely noticed the Civil Rights movement on TV. And I thought—I have friends who are black. I like them. In school, we ‘studied’ Native peoples, and I was fascinated, but there was no Native near me, they were strangely blank too, but their stories, their lives, intrigued me. But of course, we lived on their land. Where are they? Natives, for us, were pictured in popular culture as a part of the natural world—a world that was frozen in time—but in my world, in the 1960’s we could not swim in Lake Washington because there was too much of our shit in the water—and even more alarming, Lake Erie was literally catching on fire—something was very wrong. A popular commercial on TV was an “apparent” native person* looking at a pile of litter, and a tear coming down his face—us white s needed to save the planet—from ourselves. I walked to school on the inaugural Earth Day on April 22, 1970, thinking I’m going to save the planet.

s needed to save the planet—from ourselves. I walked to school on the inaugural Earth Day on April 22, 1970, thinking I’m going to save the planet.

I grew up in the white tribe called the Lutherans. My dad and my mom’s family all emigrated from Germany in the nineteenth century—as my brother said to me not long ago, “I think we have Jewish relatives—our names could have gone either way, Wellmann, Brandt and Wolfe—names that could be traced to a Jewish heritage. But we don’t know.” If I am honest I sometimes wish I was Jewish. My dad was a World War II veteran, an officer who fought the Nazis, who literally dodged bullets in battles in Germany. As he led his men in the battle for the Elbe River, he wrote about how a mortar shell hit the ground right in front of him and failed to discharge. He spoke German in his family and because of it was made a captain of a G erman POW camp, following the Allied victory. He carried the scars and trauma of those battles throughout his life.

erman POW camp, following the Allied victory. He carried the scars and trauma of those battles throughout his life.

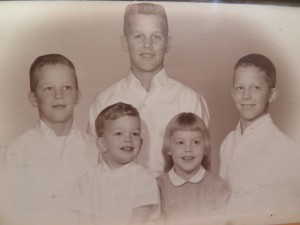

But my dad and mom’s families also rejected the Jews, Catholics and Blacks—anyone but that small tribe of Missouri Synod Lutherans. My dad and mom did not share these prejudices. They left Chicago and moved to Seattle. As a General Manager of his company my dad sought to integrate his company, to bring blacks into management. I saw my mom argue with my Chicago aunt on why they were still so racist in the Midwest. I saw the development of the Anti-Vietnam war protests in battles between my father, a Republican, and my oldest brother who became a conscientious objector and went to Canada to protest the war. It took many years for my father and brother to reconcile. I saw my three older brothers and sister experience the 60’s—becoming hip pies, turning on to drugs, communes, hitchhiking, protesting, experiencing the Jesus Freaks, Mormons, Nixon (for and against), Buddhism, and peace protests. In the 1950’s our white tribal family looked like the Beavers on TV; in the 1960s, we were unrecognizable.

pies, turning on to drugs, communes, hitchhiking, protesting, experiencing the Jesus Freaks, Mormons, Nixon (for and against), Buddhism, and peace protests. In the 1950’s our white tribal family looked like the Beavers on TV; in the 1960s, we were unrecognizable.

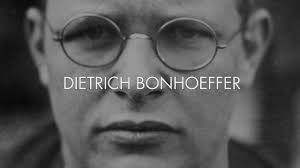

In the midst of this chaos, I read the whole Bible in Jr. High; I studied Dietrich Bonhoeffer in High School. Bonhoeffer was the great German theologian who was one of the few German Lutherans who  stood up to the Nazis; Bonhoeffer became a conspirator against Hitler and he was hung for it. He taught me to resist unjust leaders, and to resist prejudice.

stood up to the Nazis; Bonhoeffer became a conspirator against Hitler and he was hung for it. He taught me to resist unjust leaders, and to resist prejudice.

To pay for college, I worked in the summers at Gai’s Bakery. I joined the bakers union. I experienced the Italian working tribe of Seattle. I learned that one could use curse words to communicate nearly every imaginable idea. I liked the Italians; I ate in their homes. They taught me about working class people, about hard work, also about despair.

I went to Princeton Seminary—a conventional choice in practice, except for the fact that my first friend group at Seminary was the gay tribe; about half way through the year someone said to me, “You’re gay, right? You hang out with the gay community.” I didn’t know. I was truly an innocent straight, white Bellevue boy. I became friends with a gay African American young seminarian; I went to his ordination in Trenton, New Jersey—a white face in a church of a thousand African Americans, singing, praying, preaching as the minister shouted, “Teach your fish to fly.” It felt good to be there in that tribe.

I met and argued with the Seminary’s leading feminist on my first bus ride into Princeton. I had no idea what I was doing, other than standing up for prejudices I learned from my family. Following graduation from Princeton, I married a feminist and had two daughters; they both attend the University of Washington. I had three women in my family—all feminists of a kind, and I made my amends.

At the University of Chicago Divinity School my dissertation was on a large Presbyterian Church in downtown Chicago, studying how it negotiated race, class and religion in the twentieth century. Did that white tribe resist the ghettoization of Chicago’s Western neighborhoods? It didn’t. I sat with my friends, the African American staff at that church, watching the OJ Simpson trial and I cheered with them when OJ was pronounced not guilty in the  murder of his white girlfriend. I became best friends with a white South African, who was a PhD in theology at Chicago, and heard the stories of his Anti-Apartheid resistance in South Africa in the 1980’s; how he was jailed, and how his family suffered for that cause. We’ve visited our friends in South Africa twice in the last several years.

murder of his white girlfriend. I became best friends with a white South African, who was a PhD in theology at Chicago, and heard the stories of his Anti-Apartheid resistance in South Africa in the 1980’s; how he was jailed, and how his family suffered for that cause. We’ve visited our friends in South Africa twice in the last several years.

I became the Chair of the Comparative Religion Program in the Jackson School of International Studies—an unimagined possibility when I received my undergraduate degree from the UW in the 1980’s. Nonetheless, because of it, I started studying religion, violence and peace internationally. September 11, 2001 changed everything for me as a scholar. I experienced what Sherman Alexie talks about—the “results of black and white thinking are people running planes into buildings.”

I remain a part of the Christian tribe—as a Christian, I am in-between–between the kingdom of God and a country that does not live up to taking care of the orphan, the poor, the invisible ones. A country that has done great damage to other cultures and yet one that claims over and over again to be exceptional. So I live with the guilt of being in this country and accepting its privilege and knowing how much damage a dominate Christian culture has done to native people, gay people, black people, Iraqi’s, women — it makes me repent. Christ called his followers to serve the least, the last and lonely. This is an ethic that Christianity inherited from that great tribe of Hebrews, the Jewish tribe. This Hebrew and Christian ethic drives me to pursue peace, and to resist unjust authority wherever it is.

My personal existential borders were crossed more than two years ago, when my then wife of 28 years, Annette, died from a type of malignant tumor that spread to her kidneys, something her doctors had never seen. I watched her die. My tribe was cut in two. Grief is trauma. Since then I’ve read the Book of Job and I know that it is true.

I recently got married to Brooke Lucas-Roberts, an Irish woman with French Huguenot roots—she’s a resistor too, who studies psychology and theology. Through her I’ve tasted what resurrection is like in the flesh. Coming to know her and more importantly coming to be known by her has been, well, a revelation.

This is a long way to travel for a white boy from the Bellevue tribe—a blank spot at the center of the world. So today, to what what tribe do I belong? In many ways I’ve walked away from my white tribe, even as I’ve benefited from it. I no longer feel like a blank spot, in part because I’ve crossed a lot of boundaries. I recently traveled to Italy, Israel, Africa and India—it de-centers and makes me understand that there are many ways to live and love—tribal ways that inspire and provoke me. And so for now, I try to live in the in-between, the cross-tribal zone, maybe I can and maybe I can’t.

This is the water I swim in—these are the tribes to whom I visit and sometimes belong.

*By the way I was just informed that this commercial had an Italian actor “playing an Native person,” which, of course, makes it all the more colonizing and duplicitous … an American actor Espera Oscar di Corti, better known as Iron Eyes Cody (Indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2012/12/26/wheres-morality-advertising-ethics).