Answer: whatever the heck they want to do.

I know that many of us outside observers, and Christians in particular, have been worrying about proposals that the French government (which indeed does own the cathedral, as it does all cathedrals and any church built before 1905, and how that impacts the restoration is anyone’s guess) transform the fire-damaged cathedral into some sort of multicultural museum or meditation space, for instance the soundly derided Rolling Stone article claiming that

any rebuilding should be a reflection not of an old France, or the France that never was — a non-secular, white European France — but a reflection of the France of today, a France that is currently in the making

or the proposal to replace the fallen spire with a minaret, or suggestions by British architects that view the restoration as a work of art with, if needed, a “smaller church inside the ruins,” or the latest proposal, reported in the Daily Mail, of a rooftop greenhouse.

But none of us, neither those making these proposals nor the audience objecting to them, are actually French (well, except for the latest of these, by the French firm Studio NAB), and, while I’ll be the first to admit that I have a weak grasp of French culture, one thing that’s pretty clear to me is that it is not simply Anglo-American culture with lots of extra consonants at the end of their words. (The very fact that they persist in using “four-twenties and nineteen” is itself an indicator of this.) So long as we have no grounds to believe they’re going to do a Taliban (or Wahabi)-style destruction of the building, the rest of us do need to suck it up and let the French work it out, and, while I’d feel a heck of a lot more comfortable if the Catholic Church in France actually held title to the building, it’s also the case that, a proposed international competition notwithstanding, the French government seems to have no more interest in directly funding (and controlling) the restoration now than it did the work underway at the time of the fire.

And here’s a key point that we observers are forgetting:

Medieval cathedrals are houses of worship, yes.

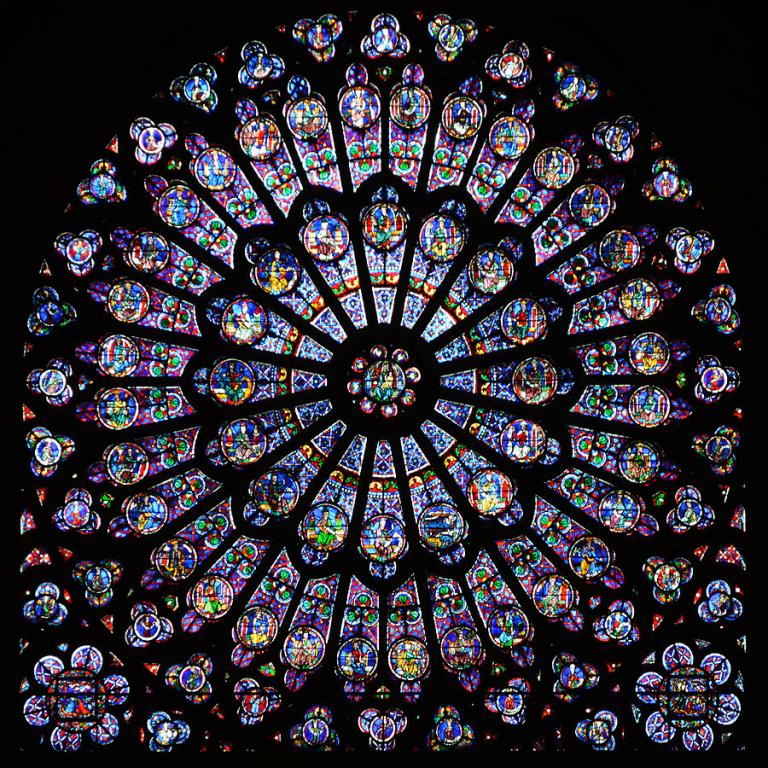

But they were also, even when they were constructed, monuments to the glory of their cities’ economic prosperity, and a celebration of the new technology the people of those cities had attained that began in what is called the “Renaissance of the Twelfth Century,” a period of economic development, revitalized trade, the development of the university, translations of Greek and Arabic texts in science, philosophy, and mathematics, and consequently the growth of cities and the beginning of the period of Gothic cathedral-building, with developments in building technology such as the flying arch allowing for greater use of windows, particularly stained glass windows, which we now take for granted but were extraordinary at the time. Notre Dame de Paris (built from 1163 – 1345), Chatres Cathedral (1194 – 1220), Reims Cathedral (1211 – 1345), and Metz Cathedral (1220 – 1550) were all on this author’s checklist during grad school travels.

Were they primarily about devotion to God? Civic showpieces? How do you differentiate when the archbishop of a medieval city governs the city, and when kings and nobility use cathedral-building to demonstrate their piety?

Here’s a useful example: the Italian cities of Siena and Florence, both wealthy and powerful at the time, had a rivalry that, well, rivals that of any American college football match-up. Siena’s Duomo (cathedral) was begun in 1196, and it’s a feast for the eyes, both inside and out, with less emphasis on stained glass than the Gothic cathedrals of France, but more interior artwork and more color in the exterior stonework.

Not to be outdone, the city fathers of Florence started building a replacement to their existing fifth-century cathedral in 1296, bequeathing to us the Duomo with its famous dome. And the city fathers of Siena, in turn, wouldn’t stand for being outdone in cathedral-building, and began to plan an addition in 1339, which would have doubled the size of the already-massive building; construction was halted with the coming of the Black Death in 1348 and never resumed, as the city lost much of its wealth along with its population, and tourists can now view the unfinished building presiding over a parking lot.

Or consider the cathedral in Augsburg, Germany.

Never heard of it? Not a prime destination? Neither the exterior nor the interior will knock your socks off, and it’s of secondary interest to tourists relative to the Basilica of Saints Ulrich and Afra, with its typically Bavarian onion dome.

The cathedral itself was initially built in Romanesque style from 1043 to 1054. As Wikipedia then says,

From 1331 to 1431 numerous Gothic elements were added, including the eastern choir.

During the Protestant Reformation, the church lost most of its religious artworks, although some were later restored. The interior, which was turned into a Baroque one during the 17th century, was partially restored to its late medieval appearance in the 19th century, with the addition of some neo-Gothic elements.

Or, as the website Sacred-Destinations.com reports,

The interior is not very harmonious due to its combination of styles and various additions, but is interesting in its details.

The German Wikipidia site further details the history of the building’s expansions, with numerous phases to the Gothic additions during the 1300s and 1400s, not following a single strategic plan but with multiple changes over time. Rather than leaving well enough alone, the city and the bishops of Augsburg were engaged in the cathedral version of “keeping up with the Joneses,” and in particular with the cathedral in Cologne, under construction at the time (though ironically the latter building, though the largest Gothic church in Northern Europe, was not completed until the 19th century).

I’m sure that experts in art history can list yet more examples, but my point is this:

We simply can’t take our modern notions of Separation of Church and State and expect them to make any sense in terms of understanding a cathedral like Notre Dame. Like so many buildings, it is a tourist destination. It is a way of looking at pretty things – windows, sculpture, soaring facades. It is a place for contemplation (though maybe necessarily in a side chapel tucked away from the crowds as in these Strasbourg cathedral photos). And it is a house of worship, which welcomes worshippers from across the globe and tries its best to encourage spiritual contemplation even among those whose intention was merely to marvel at art and architecture — and, yes, I still have my worship aid with the readings in multiple languages tucked away in the basement with other mementoes.

But I think (or at least hope) that the French get this, even if Americans don’t.