Many years ago, I was a graduate student studying medieval history. Heck, I even got as far as doing some of the initial research on a doctoral dissertation (I didn’t make it very far), which would have been about medieval “hospital sisters,” who were unique in the religious landscape in providing active service “in the world” rather than being cloistered. Now, I never managed to really find a lot of sources, and didn’t really have a good angle on them other than “hey, they are interesting,” but one thing I recall was that among the religious literature written for them were variations of commentary on Jesus’s statement that “the poor you will always have with you” — a statement that I had always figured was a sort of throwaway line justifying the use of the precious oil, but which the medieval authors took seriously: what Jesus meant is that it will always be important for us as Christians to do good works for others, for the sake of our spiritual well-being; therefore, there will always be people who will to be cared for.

Now, as it happens, in the year 2019, there are growing numbers of people who reject the idea of “good works” — by which I mean not merely the 500 year old debate about faith vs. works vs. “faith without works is dead” but the idea of private individuals and organizations caring for the needy.

For the past week or so, I’ve had the book Pressure Cooker, Why Home Cooking Won’t Solve Our Problems and What We Can Do About It, by Sarah Bowen, Joslyn Brenton, and Sinikka Eliott, sitting on my desk. It’s the sort of book that I had thought I would write a review of, in some fashion, but fundamentally, it’s not a very good book — in part because it was a follow-up to an article and they really didn’t have enough content for a book, in part because the topic was “home cooking” but the underlying issues of the nine families they profiled were, by and large, more about poverty and joblessness. So they spent lots and lots of time detailing the conversations at these families’ meals, and describing their shopping trips, but then they discuss challenges carless families face in getting to work on time, and there’s this long drawn-out episode in which a woman is being driven to the grocery store by a family member, but the fast food paycheck isn’t released until 3 pm, but she doesn’t have much time until the family member has to go to work, so they do the shopping, then get the paycheck, then come back to the store. And their bottom line is that the poor should have access to prepared meals from such sources as their children’s schools or daycares, among other things.

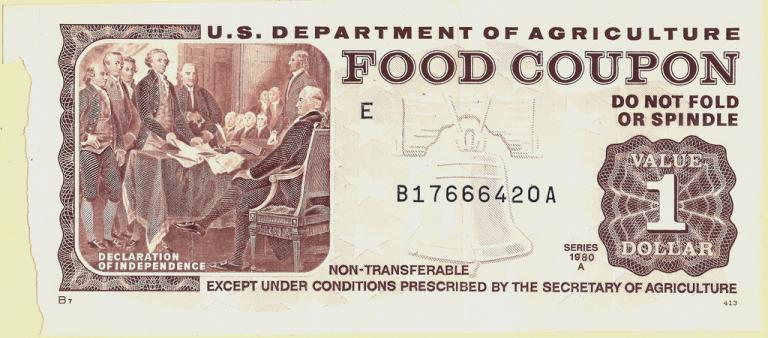

But this is what the authors say about food pantries:

But the charitable food system has also snowballed out of control . . . originally intended as a temporary stopgap to relieve suffering from relatively short-term setbacks, it has grown into “a seemingly permanent feature of the country’s landscape.”

Yet, we might ask, if these food charities are serving a need, and clearly they are, is there really a problem?

The simple answer is yes. The entrenchment of this vast system of food charities, critics point out, has negative implications: for the people who rely on food pantries and food banks, and four our ability to adequately resolve the problem of hunger in the United States.

Charitable efforts work at the individual level, by serving as a “moral safety valve,” reducing people’s discomfort with seeing visible inequality and destitution. At the governmental level, these efforts “work” by making it easier for policymakers to shed responsibility for the poor.

In other words, food pantries are bad because it allows the government to get away with not meeting 100% of the food needs of everyone living in America. (Which is easier said than done when the issue isn’t really hunger so much as low wages generally speaking, and chronic unemployment, and so on — and they acknowledge this later on in placing on their wishlist community meals sponsored by churches with sliding-scale or pay-what-you-can pricing.)

And this fits in with a larger philosophical attitude, that private charity is, in fact, not a good thing. Readers, if I had the time (and, let’s face it, the inclination), I’d find sources to cite so that you can trust that I’m not just making this up but you likely have heard these sorts of statements before:

“It is undignified and humiliating for any given individual to be dependent on charity for the necessities (or even the nicities) of life; what’s right and fair is for the government to guarantee their provision on an ongoing basis for the poor, or in a rapid and income-replacing fashion for those who lose their jobs or become disabled.”

“The wealthy should not have the privilege of donating their wealth as they see fit, because it is the community at large (through both legislators and bureaucrats making decisions on their behalf) that should be making those decisions. One billionaire might have his own ideas about education that are at odds with what the school board or the teachers or the teachers’ union believes, and it’s unfair for that billionaire to be able to decide by means of choosing to fund some things and not others. Therefore, they should be taxed to the fullest extent necessary for proper provision of services.”

“It’s simply morally wrong for billionaires to have as much money as they have, and intentions to donate that money in some nice fashion or another don’t make up for the inherent wrongness of having it in the first place.”

But let’s think about this for a minute.

Various progressives/leftists in the United States will say that they believe that they fulfill the command to care for the poor precisely by supporting at the ballot box those candidates who support extensive safety-net benefits. But look at how this plays out in the current election cycle: Elizabeth Warren, for example, is not promising to fund Medicare for All by means of a flat tax so that we all collectively care for our less fortunate neighbors. She is promising that the Billionaires and the Banks (along with a fuzzy “maintenance of effort” provision for employers) will fund healthcare for the rest of us.

And in those countries were a solid social welfare system is firmly established, where the whole wishlist of American progressives has already been met, with welfare checks large enough that no food pantry is needed, and with the fundamental lack of any concept of charity — well, I’m just not sure it’s possible to square that with the words of Jesus.

And locally, consider that local food pantries still accept your donations of nonperisable foods, but the Greater Chicago Food Depository doesn’t hesitate to say, “we prefer cash.” My local church switched to a “giving tree model” of “give cash so the head of the family can buy gifts for the children” (and now struggles to get people to take names).

Longtime readers will know that this is something that has bugged me for, well, a long time. It just doesn’t feel like “vote for the candidate most generous with social spending” counts as a Work of Mercy. And now that I’ve left a regular paying job — well, the “write the damn check” school of thought would say I really should have stuck to it in order to have more money to donate, but that hardly feels like a reasonable approach.

And here I come to the end of my comments.