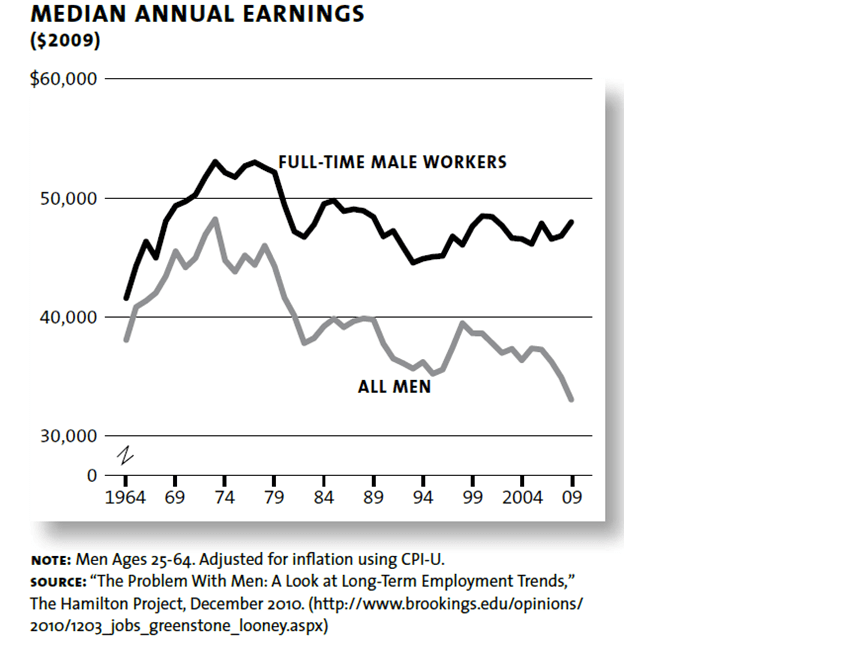

Some time ago, I wrote a number of blog posts about the troubles that boys and men were having in the U.S., that boys were struggling in school and men were struggling in the working world. Sadly, I mostly wrote these before I got into the practice of putting useful tags on the articles, and one of those that I can find, was before I transitions to Patheos, and the images didn’t make it. Nonetheless, in January of 2014, I looked at some statistics on the patterns in men’s wages over time, and the key chart is below (pulled from the Blogger editor), though the original table no longer exists at the URL listed in the caption. Even though women’s wages have been steadily growing during this time period, men’s wages have been stagnant or declining, depending on how you measure it. And, yes, this chart is a decade old (turns out, I’ve been blogging for over 10 years now!), but the trends are similar now.

Separately, in 2017, I wrote about a book on the topic of the struggles boys are having in modern-day America, Boys Adrift, which highlights struggles boys are having in school, with factors ranging from the ever-decreasing age at which children are expected to sit still and do “seatwork,” to unintended side effects of ADHD medications, to a broader “devaluation of men.” And it sure seems to me that it was here, but it may have been elsewhere, that there was a discussion around the difficulties boys were having with a shift in the way math is taught and evaluated, that just learning the mechanics isn’t enough any longer, but every problem is a “word problem” and boys are expected to be able to explain how they solved their problems.

Which brings me to my latest library book, though sadly, it was not a “library book” in the sense that I picked it up off the shelf, but instead I had to make a request for it to be purchased; the librarians didn’t seem it worthy to acquire when it first came out.

Of Boys and Men, first published in 2022, by Richard V. Reeves, tells an unfortunately too-familiar story, about the quite significant ways in which boys and men are falling behind. Boys’ grades are declining relative to girls, their graduation rates are lower, they are less likely to attend college. While men, on average, still earn more than women, there is considerable overlap, and at the lower end of the spectrum there are substantial numbers of men who are struggling, and which means that men are more likely to be unable to be the “breadwinner” in the family — which means they unable to marry in the first place because it is so rare for either men or women to consider a “role reversal” acceptable. Ethnic-minority men and poor men are struggling most of all. And there is what Reeves calls a “political stalemate” that impedes working together to solve the problems, as “the political left is in denial” and the “political right wants to turn back the clock.”

(It’s a short book and an easy read, so you, too, should request it be purchased at your library.)

But I’m going to drill down to one chapter, Chapter 6, “Non-Responders, Policies Aren’t Helping Boys and Men,” because this is where I was genuinely surprised at the key point that various programs meant to help poor/minority children, actually only helped the girls.

The Kalamazoo Promise, the first-of-its-kind promise by an anonymous benefactor to pay for tuition at in-state colleges for students attending public schools in Kalamazoo? Studies say it had a dramatic impact — on the girls, whose college completion rates increased 45%. At the same time, the men’s rates “didn’t budge.” And researchers don’t have an explanation why, though Reeves interviewed a young Kalamazooian black man who reported that he struggled to find a path in college, but observed that “females are just working harder, doing better, asking more questions,” and explained that, when he did find his path, he “always sought out female-dominated study groups because ‘you just knew they would get it done.'”

Another program, a support program called Stay the Course, at a Fort Worth community college, similarly saw great results — but only for women.

The three celebrated preschool programs, long-cited as proof of the benefits of intensive early-childhood education for poor children, the Abecedarian, Perry, and the Early Training Project, showed “no significant long-term benefits for boys.”

A special summer reading program in North Carolina? Great benefits for girls, no statistically significant effect for boys.

Urban boarding schools in Baltimore and DC? Again, benefits only for the girls.

And there were more on Reeves’ list. Perhaps he cherry-picked these, but I doubt it.

And if you turn the page, Reeves lists jobs training programs with the same pattern — significant benefits for women, not for men.

Now, Reeves is honest. He doesn’t claim to have an explanation and a “fix” for why these programs didn’t work. Although he offers some ideas of his own in the last section of the book (redshirting boys since — see above — they just aren’t ready for the demands now being placed on kindergartners; encouraging men to enter health and education fields; and encouraging more active fathers, whether or not they are married to their children’s mothers), none of these are quick-fixes, but instead can only benefit the next generation of men.