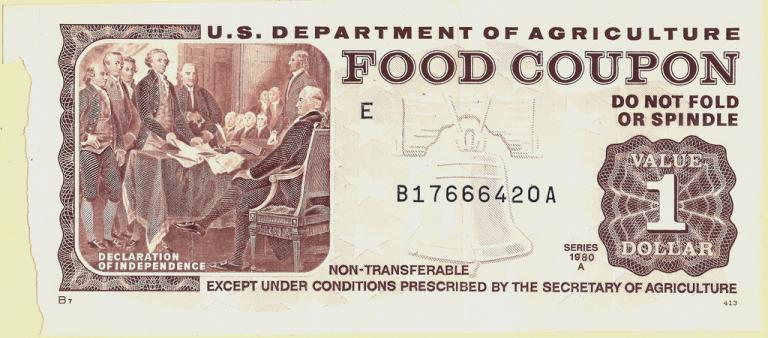

So in the last two posts I’ve mentioned the book Pressure Cooker, which wants to talk about such issues as the challenges the poor have using their food stamps to shop, and the pressures (some) middle class women perceive to put from-scratch meals on the table every night, but can’t really pull this together into a coherent whole. The book bops back and forth from one family to the next, of the 9 women and their families which it profiles, mostly, but not all, poor women.

But in light of my prior blogposts on food stamps, I wanted to look closer at these families. Some of these families are among the “working poor” and would clearly meet the SNAP work requirement. In another instance, a grandmother cares for her preschool grandchildren, so she’d qualify as a caregiver even if she’s not old enough to be waived from work due to age. A husband has Parkinson’s. And so on.

But what about Latrell?

Following one of the families as they are profiled through the book, he is Leanne’s husband (the book uses pseudonyms throughout). Leanne is, in the summer of 2013, working part-time as a McDonald’s cashier, and attends a technical college part-time as well. Latrell is unemployed, attributed to the 2007 recession.

No, the stock photo above is not of Leanne and Latrell. But I bet Leanne wishes it were.

Leanne, in addition to work and school, cooks for her family. She is the one who does the shopping, who goes to the food pantry when the food stamps run out, three kids in tow. She is the one who sometimes skips meals to ensure the kids and her husband have enough to eat. She puts up with her mother’s harangues as the cost of getting rides to the grocery store, since only more-expensive corner stores are in walking distance. She manages the family finances, signs the school permission slip, supervises the homework, cuddles the youngest, a one year old.

In another chapter (chapter 10), Leanne is hosting a July 4th cookout. We learn that her sons are seven and eight years old, and as the chapter begins, Leanne is on her way to the corner store to buy a treat for the oldest because Latrell took the middle one for a treat earlier, so it’s only fair. When she returns from the story, having bought treats for both boys and the other tag-along children, she enlists Latrell in glazing the ribs. Then Latrell’s brother calls; he wants him to go with him to a city an hour’s drive away, but Leanne says no. Later the baby wakes up from her nap and Leanne changes her diaper. Latrell’s brother calls again another time and, as the chapter ends, Latrell is still talking about making the trip with his brother. (What’s in Rocky Mount? We never find out.)

Later (chapter 18), we observe Leanne trying to manage grocery-shopping when the food stamps were not replenished as expected. Fortunately, it’s payday, and Leanne’s mother will take her to get her paycheck, then to the grocery store. (We’re now told that she “manages Leanne’s money” — what this means is not clear.) Latrell “looks on” while the women make the plan, then his role is to install the car seat so that they can take the baby with them, though the boys stay at home with Latrell.

They proceed with the shopping trip, then return home and Latrell helps unload the groceries, then he fumes that the Oodles of Noodles packages she got were shrimp rather than chicken-flavored. Then Leanne gets ready for her 5:00 work shift, when “Latrell will be ‘babysitting’ again” (the authors put “babysitting” in quotation marks).

In chapter 22, we follow Leanne, her mother, one of the boys and the baby to a trip to the food pantry, where they’re also able to pick up clothes for the children. When they return home, Latrell is playing basketball (by himself? with the other boy?), but he stops to help unload the food pantry bags, but wanders off again before all the food is put away. Leanne complains to her mother about Latrell, and her mother says, “You a single parent, basically.”

And that’s the last we hear of Latrell.

So is he a good-for-nothing lout who does nothing to contribute to the welfare of his family, leaving Leanne to support the family on Food Stamps and a half-time McDonald’s income? Would a full-enforced work requirement get him off his lazy a**? Did he have a “regular” job before the recession and his pride won’t let him work at McDonalds, or are the authors charitably attributing his lack of work to the economy when he doesn’t actually look for a job in the first place?

That’s plausible.

But there are holes. The biggest of these is simply – who is taking care of the baby? (Sure, the baby is in fact a baby, so that doesn’t explain what he may have been doing before the baby was born, after the older boys had started school.) Is Latrell the baby’s caregiver when Leanne is at work or school, or does she cobble together caregiving from a whole slew of friends and neighbors, or does she have the baby in a daycare program during daytime hours? (You’d think the latter would get some sort of mention for its impact on the family budget, every bit as much as the conversation about whether using the paycheck on groceries instead of utility bills will cause problems causes a lament about the need families face to prioritize spending in one way or another, but, then again, in the whole exchange around using her paycheck for groceries, they don’t talk about the need to pay rent, either.)

Now, again, this is a book about women, and in one respect it seems unreasonable to chide the authors for spending insufficient time talking about men that are not the topic of the book. But the men do actually matter. If Latrell is actually providing childcare, that’s important to acknowledge. And if, as he’s portrayed, he truly does nothing to contribute to the family’s well-being other than instances of caregiving that are so infrequent and reluctantly taken-on as to be deemed “babysitting,” then that also matters. This is not the way it should be. If a work requirement for food stamps can nudge him into doing something, even for just 20 hours a week, that’s a win, isn’t it? And if it wouldn’t work, if he’d say, “fine, cut off my food stamps, I’ll just take from my wife and kids,” that’s a problem the answer to which isn’t “give everyone food stamps (or rent or whatever) unconditionally.”