Here we can see something of the problem with contemporary Christian art, especially Christian rock (though not just Christian rock, and we ought keep that in mind). It takes as its content something religious, but it is directed outward (even if mostly at Christians, one imagines it is also intended evangelically). Formally, however, it adopts the kitschiest of contemporary tropes without attempting to understand what actually makes something attractive to someone in a given historical moment, i.e. how beauty is manifesting itself. By merely appropriate kitsch, it fails to innovate, reverse trends, or in any meaningful sense play with what it has been given; as such it is unlikely to endure (let alone seize anyone’s attention now).

The culture is no longer Christian in the way it once was; as a result, the Lydgate approach simply is not very effective. If it worked for Lydgate, that’s because he was speaking to a largely, if not nearly entirely, Catholic community that couldn’t get enough of what he was doing. Yet now he’s rarely heard about, because his work does not transcend its own moment (though one must give him credit for speaking to the tastes of the day). In sum, such art retains too much of the overt didacticism of church art without realizing that the context for contemporary reception is very different than it once was.

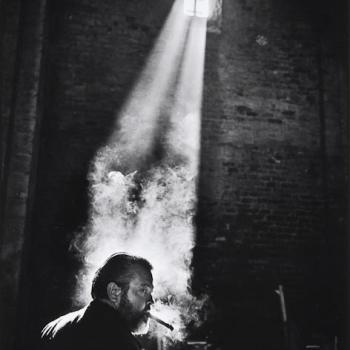

The other form of “religious” art, however, helps to bridge this gap. On the one hand, Bacon’s piece (available above) does the important work of continuing to explore a tradition. By looking at earlier form and playing with it (specifically the form of a pope’s body and head) he (implicitly) keeps religious symbolism in the popular consciousness even as he seeks ways to (for his own purposes) transform existing generic conventions. On the other, Tolkien and Warhol are doing the important work of showcasing a Christian worldview through their art; formally (and even in terms of content) there is nothing overtly didactic going on. The symbols in use do not require knowledge of the entire tradition; rather, symbols from the popular consciousness are appropriated, retouched, and, in a sense, baptized, allowing for limitless commentary on the state of things, and, one hopes, a revitalization of artistic evangelism.

To be clear: I don’t promise to be absolutely correct about any of the above. Tolkien and Warhol have been chosen because of my familiarity with them—I’d need to flesh my point out further (and think about it more deeply) before I could make stronger, more specific claims. But it seems to me that the point is simple: part of the function of the religious artist today is to bring the lessons of the Faith to the world outside. It’s a meaningful form of evangelism that allows for a deeper exploration of artistic traditions within a next context. Even the hallowed religious forms of yesteryear (many of which are still central to the Faith; don’t get me wrong—I don’t want horrid, plain cathedrals) came into existence within specific social conditions, social conditions now dominated by nonbelievers. Should we then be afraid to create religious art that can speak to a secular world?