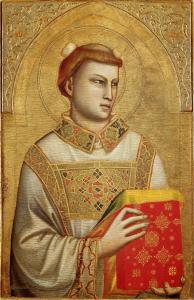

In the West, today marks the Feast of St. Stephen, deacon and first-recorded martyr. Tomorrow, for those Eastern Churches using the Gregorian or Revised Julian calendars (including my own Ruthenian Church), will bring the same celebration, a day to reflect on the first man to “fight the good fight,” to win the stephanos, the crown of martyrdom. December 26th is a state holiday in many countries, especially in Europe, a day to mark the ongoing joy of the Christmas Season, even as it provides time for reflection upon what we all might—theoretically—be called to do.

In thinking about St. Stephen this year, however, I felt especially moved by some of the shorter passages describing him and his speech. His martyrdom is glorious, his almsgiving as a deacon more than admirable, but this deacon attests to something too often forgotten by Christians today—our religion’s inherent universalism.

What do I mean by “universalism?” Certainly I don’t mean “universal salvation” as reputedly espoused by George MacDonald. Rather, I mean the idea that Christ’s message is necessarily a universal one, for all peoples at all times. Universalisms are evangelical by nature; these religions or philosophies seek to bring other groups into their fold. Whatever my dislike of it, Liberalism is certainly a universalism (a point the Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt never tired of attacking). Islam too counts, as does socialism. Their “opposites” might be called “particularisms,” positions like fascism, Nazism, and tribalism, in which specific groups are either privileged as “intrinsically best” or otherwise said to have necessary forms of organization inherent in their own ways of being in the world.

The issue is, of course, more complicated than this. Hegel, for example, thought that where there was a particular, there must also be the universal—the two could not, in any true formulation, be divorced:

Hegel’s Concept has three moments: universality (Allgemeinheit), particularity (Besonderheit), and singularity (Einzeinheit) (sometimes translated as individuality). The precise logical order of explanation is the following: The starting point of the Concept is the universal, which is the essence or substance that has already been identified in the logic of Essence. The Concept then proceeds to an explanation of the particulars, which presupposes the nature of the universal, and adds additional determinations in order to differentiate the presupposed universal into its particular forms. In other words, the particulars are explained as particular forms of the universal itself, as ‘self-particularizations’ of the presupposed universal. It is in this sense that the universal substance is also a ‘subject’ that creates its own particular forms. Finally, the Concept proceeds to singularity, in which the universal achieves concrete existence and the perfect embodiment in a particular form. (Fred Moseley)

As with most any writing about Hegel (or by him), that all sounds very confusing, but the basic idea is that some universal idea (say, Christianity) is what it is only insofar as it is made up of particular forms (say, various rites: Roman, Byzantine, Syriac, and so on). Universalism is thus not merely some homogenizing idea that requires subordination of all existing groups and ideas to it; rather, it finds its fullest expression precisely in that diversity—a unitary diversity, a diverse unity. This is effectively what being catholic means; it is what being Catholic should mean.

What does all of this have to do with St. Stephen? The Acts of the Apostles implies that Stephen was a Greek-speaking Jew, who was appointed by the Twelve to help ensure an equitable distribution of resources between the Hellenistic widows and the Hebrew ones:

At that time, as the number of disciples continued to grow, the Hellenists complained against the Hebrews because their widows were being neglected in the daily distribution. So the Twelve called together the community of the disciples and said, “It is not right for us to neglect the word of God to serve at table. Brothers, select from among you seven reputable men, filled with the Spirit and wisdom, whom we shall appoint to this task, whereas we shall devote ourselves to prayer and to the ministry of the word.” The proposal was acceptable to the whole community, so they chose Stephen, a man filled with faith and the holy Spirit, also Philip, Prochorus, Nicanor, Timon, Parmenas, and Nicholas of Antioch, a convert to Judaism. (Acts 6:1-5)