Nixon won in part because Liberalism was in the midst of a transformation. Lyndon Johnson had finally allied the Democratic Party to a post-New Deal technocracy, alienating Southerners in the process. The GOP was fraying at the seams, caught between its Liberal wing and the conservatives. Nixon split the difference and the rest is history.

What if Trump means something similar? He’s not unlike Nixon. In a way, he’s splitting the difference found in his own party. On the one hand, there’s the libertarian strain—Ron Paul, (at one time anyway) Rand Paul. Then there’s the corporate strain, best represented by the descendants of Rockefeller Republicans—Mitt Romney, George Bush, Lincoln Chafee. Last, we have the semi-populists. This group looks a bit different depending on who you ask: at times they seem to be the Tea Party. But they like tariffs? They want manufacturing jobs, but they don’t want the ones brought by renewable energy investments. The last wing is the most Trumpian; in fact, it’s as amorphous as he is.

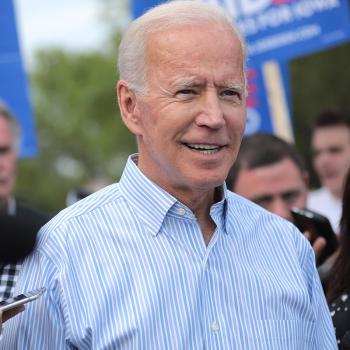

Trump has come to dominate his party in the way Nixon seemed to—he did demand loyalty after all. So what happens to the GOP after Trump? I don’t know if Trump will be impeached (let’s not forget your party can control Congress and you can still get impeached, especially if there’s material evidence of a crime, as in Nixon’s case). I don’t even know if he’s done anything wrong. But even if nothing happens to him, I find it hard to believe that the GOP can remain wedded to his principles (in part because they seem invisible to anyone but his most ardent supporters). All the “RINOs” have been slain or have converted. If Nixon teaches us anything, it’s that something must give.

Some seem to think this means a new shot for the Rockefeller Republicans; “bring back the party of pragmatism,” they yell. This, however, seems very unlikely. They fell apart once as a result of material circumstances (the weakening of WASP power bases, the influx of Southern Republicans, shifts in urban demographics, etc.). Plus, if Paul Ryan is a RINO, I don’t see Margaret Chase Smith riding into Washington, D.C. in triumph any time soon.

I see it this way: one scenario has Trump impeached, in which case we’re likely to see the resurgence of the Paul Ryan types. They fell at Trump’s feet, but with him defeated, they can recant, find some absolution, and hammer the Democrats. This is possible, but not, I think, the most likely version of events. More likely is something like the atrophying (and possible destruction of) Liberalism within the GOP. The fall of the Rockefeller Republicans gave us neoliberalism, a shove to the Right. The only think Right of neoliberalism (but still at all Liberal) is Libertarianism. But what’s been happening to lots of Libertarians these days?

Libertarianism has an alt-right problem. Many prominent leaders of the alt-right have, at some point, identified as libertarian. I am curious as to… why?

Milo Yiannopoulos has billed himself (and has been billed by others) as libertarian. About a year ago, he came clean about that. According to Business Insider, the alt-right troll Tim Gionet (aka “Baked Alaska”) formerly “identified as a carefree, easygoing libertarian” who “supported Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul’s bid for the White House, firmly opposed the war on drugs, and championed the cause of Black Lives Matter…”

Gavin McInnes bills himself as a libertarian, but he founded the Proud Boys―a men’s rights group that is considered part of the alt-right. Augustus Invictus, a Florida attorney who literally drank goat’s blood as part of an animal sacrifice, ran for senate in the 2016 Libertarian Party primary and spoke at Liberty Fest. Recently popular among college libertarians, Stefan Molyneux evolved into a pro-Trump alt-righter. And Richard Spencer was thrown out of the International Students for Liberty conference this year after crashing the event.

It is also true that many of today’s alt-righters are disaffected conservatives. However, there are many more conservatives in this country than there are libertarians, which suggests a disproportionate number of today’s prominent alt-righters began as libertarians.

“It’s ironic that some of these people start off calling themselves libertarian, but they are the antithesis of everything that the libertarian project stands for—which is cosmopolitanism versus parochialism, individualism vs. group identity, and libertarianism or autonomy versus authoritarianism,” Nick Gillespie, editor in chief of Reason.com tells me. (The Daily Beast)

I’m not espousing anything new here. The Frankfurt School saw fascism (and it’s not much important to me whether we call Trump a fascist or not—what matters is his pragmatic illiberalism) as the death gasp of Liberalism. The New Yorker published this in 2016:

Humans think in stories rather than in facts, numbers, or tables, and the simpler the story, the better. The story that has ruled our world in the past few decades is what we might call the Liberal Story. It was a simple and attractive tale, but it is now collapsing, and so far no new story has emerged to fill the vacuum. Instead, we get Donald Trump.

The Liberal Story says that if we only liberalize and globalize our political and economic systems, we will produce paradise on earth, or at least peace and prosperity for all. According to this story—accepted, in slight variations, by George W. Bush and Barack Obama alike—humankind is inevitably marching toward a global society of free markets and democratic politics.

So why bother repeating this? The answer is in the quote above—because it matters what we do with the corpse of Liberalism. If it’s gone, which way will we go. There are plenty illiberal or anti-liberal ideologies out there. Take your pick: Marxism, Anarchism, Mutualism, Fascism, Nazism, Titoism, Distributism, Integralism, etc. These imagine wildly different worlds—unimaginably disparate futures. We have to ask ourselves which we, as Christians, would most likely to imagine. Too often we think merely in terms of policy proposals (abortion, gay marriage, taxes, unions, whatever). But each of these proposals, each of these ideas, is ultimately rooted in a story we tell ourselves, a story about what the past means and what the future can be. We live in a strange moment, if only because it’s deeply unclear which story we will choose to tell ourselves; it’s unclear which narrative (which will set the parameters for policy debates) will guide us.

We have to ask this now. Otherwise, we’ll end up like the Rockefeller Republicans—full of good ideas, but hopelessly lost to the never-ending tides of history.