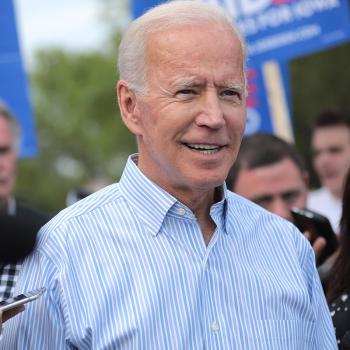

I’m no fan of Donald Trump. I wouldn’t say I’m in the #Resistance. My favorite candidates in the current primary are probably Sanders and Warren. I’ve got some love for AOC and mostly find the way the Democrats have chosen to do things over the last couple of years ineffectual, though they’ve achieved some modest successes—like their small victory in the midterms. Trump, however, tells us something about the actual nature of politics, something that the Dems have generally struggled with. Politics is a narrative art; it’s about spinning tales, myths, that people can believe in and act on. Capture a person’s mind and you mobilize him. As paradigms fail, they fade away.

It’s the art of storytelling that motivates the masses as much as anything else. The story doesn’t need to be coherent (very few are). The French Revolution was not a program, but a half-spontaneous outpouring of outrage centered on several key terms. Obama’s campaign is well known for its sloganeering. Ronald Reagan was, after all, a B-movie actor who knew how to play a crowd. Trump, for all his bumbling and basic incoherence, plays with language in a way that engages people. Call it “propaganda”; call it “mythmaking.” These can be distilled into images: the king and father God of the Middle Ages, the worker, raising hammer and sickle against a backdrop of wheat of East Germany. They can also be assortments of words and monikers: “low-energy Jeb,” “bigly,” “crisis,” “coup.”

These are the same sorts of stories that captivate us in literary texts. A book presents a certain world and asks the reader to engage it, to immerse him- or herself in it, to believe it and its parameters if only for a moment. Such tales can claim to be “realistic,” thereby informing how we think about the “real world.” They can be so patently fantastic that they, paradoxically, reveal the absurdities of our world, our lives.

Stories are, of course, thus dangerous. That’s why Plato suggested the poets be expelled from the ideal city:

And now we may fairly take him and place him by the side of the painter, for he is like him in two ways: first, inasmuch as his creations have an inferior degree of truth—in this, I say, he is like him; and he is also like him in being concerned with an inferior part of the soul; and therefore we shall be right in refusing to admit him into a well-ordered State, because he awakens and nourishes and strengthens the feelings and impairs the reason. As in a city when the evil are permitted to have authority and the good are put out of the way, so in the soul of man, as we maintain, the imitative poet implants an evil constitution, for he indulges the irrational nature which has no discernment of greater and less, but thinks the same thing at one time great and at another small; he is a manufacturer of images and is very far removed from the truth. (Republic Book X)

If one believes one way of being in the world to be true, one feels threatened by emerging, fake stories. As Aristotle tells us, these sorts of stories are the most dangerous in democracies, where the majority of people can be exposed to them, moved by them:

Again, the evil practices of the last and worst form of democracy are all found in tyrannies. Such are the power given to women in their families in the hope that they will inform against their husbands, and the license which is allowed to slaves in order that they may betray their masters; for slaves and women do not conspire against tyrants; and they are of course friendly to tyrannies and also to democracies, since under them they have a good time. For the people too would fain be a monarch, and therefore by them, as well as by the tyrant, the flatterer is held in honor; in democracies he is the demagogue; and the tyrant also has those who associate with him in a humble spirit, which is a work of flattery.(Politics V)

We don’t need to follow Aristotle’s taxonomy to see the basic point: stories can be used to flatter certain groups, convince them they’re right, and thereby mobilize them for action, perhaps ending in tyranny.