As a kid, I watched the History Channel special on the American Revolution every year. I loved learning about the origins of my country. Coming as I do from a patriotic family, a family in which both grandfathers fought in World War Two, one of them at D-Day and Bastogne, the whole ritual was imbued with filial significance. I brought a book about the 101st Airborne, my grandpa’s division, to my high school for a grown-up show-and-tell. I would look at his uniform, at the various goodies he had brought back from Europe, mostly—he is supposed to have said—from Nazis he had killed. This interest went beyond military history: on Presidents’ Day, I took in the annual History Channel special—little TV index cards displaying “presidential stats” and all.

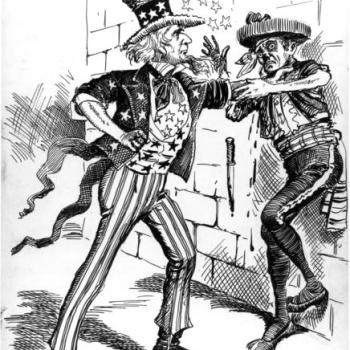

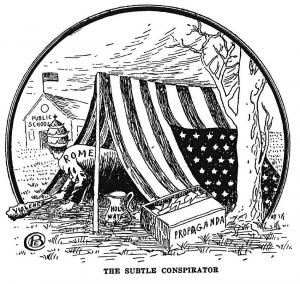

When I was older—and as I became more religious—this relationship became more ambiguous. I still loved history, but my obsession with American itself cooled, even soured a bit. I learned about the anti-Catholicism of many Americans up through the twentieth century, about rage-filled political cartoons and the propaganda of all sorts directed at my Slovak forefathers. I began to explore the history of Catholic Social Thought. However one reads Rerum Novarum, whether through the lens of someone like de Maistre or from the viewpoint of Herbert McCabe, it’s hard to see our history as entirely consonant with American constitutionalism. Being a medievalist only deepened my conviction that there was something afoot; take a gander at Unam Sanctam or the work of John of Salisbury and tell me with a straight face that they prefigure America’s Founding Fathers.

Matters were only made harder by my coming of age at a very peculiar moment in American Catholicism. There’s the Integralist revival, the burgeoning of post-Liberal theology, and, of course, there were the Tradinistas. The election of Trump, the cracking of the Religious Right, the recent crises in the Church—all of these have played a role in what is shaping up to be our age’s general reevaluation of the relationship between Catholicism and the US. Being young, Catholic, and American has become, for many, a problem to be interrogated, rather than an identity to be taken for granted, let alone celebrated.

With this in mind, I would like to examine two arguments often offered in defense of the US from a Catholic perspective: first, that here we found freedom of religion, and second that this nation’s long history of anti-Catholicism is mostly left behind, that in a post-JFK world, remembering those times is dredging up memories better forgotten. From there, I will offer my thoughts on this identity, “Catholic American,” and how it sits with me on this Fourth of July.

Sometimes I have heard it said that we display American flags in our churches because this is a place where we are allowed to express ourselves freely; we ought to show our appreciation for the fact that we are not persecuted, that we can live as we wish to. Further, some might say, nationalism and Catholicism have long gone hand in hand—look at the post-Constantinian Roman Empire, the Gallicans in France, or modern Poland. This second group, of course, is not generally well-remembered, putting nation before Church as they often did. Modern Poland, while its Catholicism is admirable, its politics (which might be moderated by a closer adherence to Church teaching) are not always so. The empire introduced us to the risk of caesaropapism.

The risk seems all the greater in a country that demands great love from its citizens. We display our national flag in a way unknown in most of the rest of the world (at least when it comes to display by individuals). Europeans think the Pledge of Allegiance is just plain weird (fun historical fact: we owe the Pledge to a socialist and Baptist minister, Francis Bellamy). On top of all this, there is a special danger in nationalism for Catholics. Simone Weil picks up this strand of the tradition:

Our patriotism comes straight from the Romans. This is why French children are encouraged to seek inspiration for it in Corneille. It is a pagan virtue, if these two words are compatible. The word pagan, when applied to Rome, early possesses the significance charged with horror which the early Christian controversialists gave it. The Romans really were an atheistic and idolatrous people; not idolatrous with regard to images made of stone or bronze, but idolatrous with regard to themselves. It is this idolatry of self which they have bequeathed to us in the form of patriotism. (The Need for Roots 220)