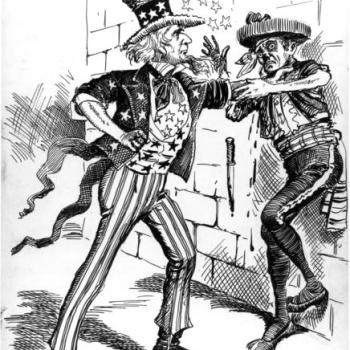

Can “religious freedom,” then, really be why we keep flags in churches? Is Simone Weil not right—at least in part? Do we not owe God and our neighbor everything, far before the abstract concept of “the nation”? It seems to me that this is especially worth stating in a time when many Catholics are using their patriotism as a way to attack (mostly) other Catholics who are trying to migrate here! Are we not, in deploying stereotypes, subjecting others to the scorn and hate that we once knew, all in the name of our love of country? It seems to me that, rather than bow before our nation, we ought delve more deeply into our tradition, working hard to see what other concepts besides “religious freedom” might mean something for 21st-century Catholic Americans.

What then of the past? Should we merely forget it, the discrimination and the prejudice? For starters, we might not want to do so because setting the past aside can blind us to our re-inscribing it. If we forget how we were treated, we risk treating others that way. I do not mean that we cannot forgive: America has been good to my family, at least on the whole; it has been bad to many others. I simply mean that repressing the truth may bring it back—this time through us—with doubled force.

Further, remembering this history might better attune us to the histories of other groups. There are points of intersection here: between Catholics and Native Americans, for example. We might better come to see how our nation has failed or been mistaken by thinking with other groups who have experienced discrimination here—a position we once knew, and, with all this in mind, perhaps can better see in the faces of our neighbors.

In this sense, remembering also puts us in a position to better live out Catholic Social Teaching, which, sometimes is effaced by American ideology. A friend of mine has written eloquently about how, in the modern US, we are taught to think of economic problems in a way counter to the tradition; we ought to move beyond this:

The only thing that makes Catholic Social Teaching, as a modern phenomenon, interesting or in any way different from what came before, is its context, which has involved the repeated necessity of responding to the novel idea, proposed by Enlightenment thinkers, that economic questions were intrinsically non-moral and ought to be evaluated on purely “objective” and “scientific” bases, rather than on the ethical basis of justice. This gradual removal of economic questions from the purview of justice and ethical development over the last centuries is now, in our day, essentially complete: the very terms “economic justice” and “social justice” have become for many simply contradictions in terms, alternately denied or else abused as signs for the merely arbitrary and unlimited extension of voluntaristic “rights” to more and more people. In the view of many “scientific” economists, the only possible sense of “justice” in economics is in the completely arbitrary terms set down in a voluntaristic legal contract, or at best the “objective” quantitative measures of monetary exchange and economic growth contained in things like GDP—any external, objective ethical norms beyond these are not only illegitimate, but absurd and self-contradictory. (“What is Catholic Social Teaching?”)

There is, to put it briefly, room for us to grow; remembering our past is one important way to do this. In not forgetting, we find an opportunity to deepen our knowledge of our traditions, something America once asked us to set aside.

Now, what does all this mean? Does it mean that we shouldn’t pray for our country? Does it mean that we should not hope for good leaders or thank God for the blessings of health, happiness, and safety? No, of course not. Sometimes praying for a nation means praying that it becomes a more moral place; sometimes hoping for our leaders means hoping they rectify their ways. Still, we ought to do these things. God, after all, places us in communities.

That, however, is just the key: communities. We are first and foremost members of the Church an the human race, God’s beloved creation. Whatever affection we may feel for our country must be tempered by these facts; such feelings of belonging should not lead us to deny the failings of our people and place. In fact, it should lead us to strive to do better, to conform our communities to the ways of the Lord, to be perfect as our Heavenly Father is perfect.

In short, I cannot say that I have immense hope in or for the United States at this point; I have many reasons to be suspicious of it, in fact. Yet I still pray for it; I still hope for it. That’s the best we can do.