Source and License

Liliana Cavani’s The Skin (1981) only has 13 user reviews on IMDb, three of which are from American soldiers who played extras in the film (or their children). None of the military once-overs deal with its content, and at least one recounts how grunts who saw the movie upon release spent its runtime Where’s Waldoing themselves. I cannot imagine a more powerful indication of the film’s success. It sets out to show the realities of Neapolitan life under Allied occupation during World War Two, and it does so with unrelenting humor, horror, and attention to detail.

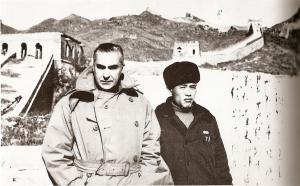

Based on a 1949 autobiographical novel by Curzio Malaparte, the film’s narrative is impressionistic. There is no one single protagonist but rather a variety of points of view: an American general (Burt Lancaster) obsessed with positive media coverage, a cynical Italian liaison (Marcello Mastroianni), an American aviatrix and senator’s wife who comes to Italy to get her picture in the papers pretending at a a goodwill mission (Alexandra King), and a hapless American officer (Ken Marshall). The liaison, based on and named after Malaparte, is weary with his American allies. Previously a fascist, he mocks his new comrades’ disgust: “20 years ago, Winston Churchill came here and said, ‘If I were an Italian, I would join the Fascist Party.’ Well, I am Italian!” Seeing the suffering of his people and how little the invaders do to help, he spends much of the film wandering around, showing Alexandra King’s character the unbelievable cruelties that could be brought to an end, if only the Americans would give the people bread, rather than bargain for Nazi prisoners of war with gangsters.

These cruelties define the movie and make it an incredibly difficult watch. People are meat, skin over flesh for consumption. We witness prostitutes wearing blonde pubic wigs to attract Black soldiers (we are assured that Black soldiers prefer blonde women). We see mothers selling their children to grunts. Hints of cannibalism suffuse the entire tale, even as the wealthy guests of Burt Lancaster’s character eat delicacies from waiters in powdered wigs (a sign of the American’s misconceptions about European etiquette—outdated by a few centuries). Even these sumptuous dishes are not always what they appear. In one scene, Malaparte lets slip to some American soldiers that his oxtail tastes off. He thinks it impolite to say anything but then reveals bones in the shape of a human hand. Is he kidding? He insists he is not. We cannot be sure. But if this is the state of the occupiers, how much worse must things be for ordinary people?

Very bad. Much of The Skin displays decaying (though beautiful) old slums filled with weary, hungry people. Dead bodies litter the streets. There simply aren’t enough wagons to take away all the corpses. Mines explode and kill anyone dumb or desperate enough to venture outside approved areas. Soldiers rape and extort at every opportunity and are themselves mugged by gangsters, victims of their own intoxication in victory. Late in the film, Mt. Vesuvius erupts, giving us a fantastic set piece, one that makes plain what the movie has been saying all along: living like this is like living in the apocalypse. Indeed, for these people, fascism followed by war and Allied occupation may as well be the end of days. What else can you call it when people drop dead like flies?

I’d feel bad giving too much away. The Skin works so well precisely because of how shocking it is, how powerfully it combines the ordinary and the extraordinary, blending the dull limestone palate of everyday life with gore and off-kilter comedy only possible under conditions of near hopelessness. I am reminded, in leaving off, of Jimmy Wren (the American officer’s) late-in-the-film encounter with a starving prostitute as the volcano’s ash spills across Naples. “Come on! We’ve got to go!” “Go where?” she retorts. “Go where? This is my home. I have nowhere else to go.” Such is the movie in miniature: to be a tourist in war, a spectator comes with privileges—escape, freedom. For the people of Naples, there is no escape. Liberation means freedom only ironically. Starvation, plague, and violence will continue even as the Allied troops march on (like Mussolini) to Rome.