Source: Wikimedia

Public Domain

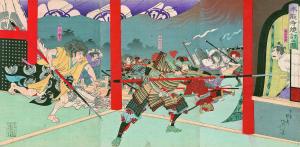

Based on a novel of the same name by the director, Takeshi Kitano’s latest film Kubi (2023) assumes substantial historical foreknowledge. The events it depicts are, I assume, famous enough in Japan to merit little exposition. Covering the Honnō-ji Incident is a bit like staging Benedict Arnold’s betrayal or depicting the Battle of Gettysburg—most people interested enough to see the film will have a basic grasp of the context. Given my longtime fascination with this period in Japanese history, I did not need the background, but it bears saying that, as much as I enjoyed the film, I cannot recommend it to anyone without sufficient contextual understanding. Without that, Beat Takeshi’s latest is little more than a breakneck parade of scheming balding men with topknots and katanas.

At the film’s center lies betrayal. Hideyoshi Hashiba (Beat Takeshi), Akechi Mitsuhide (Hidetoshi Nishjima), and Tokugawa Ieyasu (Kaoru Kobayashi) compete to become Oda Nobunaga’s (Ryo Kase) successor. Late sixteenth century Japan saw the end of stable central authority. Nobunaga represented the possibility of unity. Announcing he thinks his sons too incompetent to succeed him, he lets it be known that he will choose an heir from among his generals. Kubi amounts to a retelling of those events—samurai jockeying for power.

As with all Kitano films, comedy pokes through otherwise serious circumstances. Each of these prospective heirs is either older than Nobunaga or about his age. He is a cruel man, who, we learn early on, has no intention of handing any of his subordinates the reins of power. In his heart, sex and violence are inseparable. He will just as soon force a man to eat an apple off the tip of a sword as he will kiss the man’s scarred and bloody mouth. Liberated by power, he sexually and physically assaults his subordinates. No one, in a word, likes him. And yet, they go to absurd lengths to flatter and please him. Kitano finds this situation funny. I do too.

In each case, the director transposes this revisionist set of ideas onto more popular historiography, sometimes resurrecting Edo Period theories to do so. Often depicted as a traitorous man of ambition, here Akechi Mitsuhide oozes a species of gullible romanticism. His initial betrayal involves sheltering his lover, another general of Nobunaga’s who rises in rebellion. While he eventually turns on this lover (likely on account of having found a new one), he never seems to be in charge. Beat Takeshi’s Hideyoshi “Monkey” Hashiba tricks him into attacking Nobunaga at Honnō-ji. As in more typical portrayals, the former peasant turned warlord Hideyoshi is cunning and funny. Unlike in these versions, however, Beat Takeshi’s Monkey becomes the classic Kitano Yakuza boss: a man who can (and does) laugh at suffering.

That comedy arises from such unflinching bloodiness puts Kubi squarely in the typical Kitano Yakuza film mold. The Outrage trilogy (2010-2017) especially showcases unending betrayals, a violent nihilism that drains anyone who touches it of the will to live. And yet, what else is there to do? How else to sate your lust or greed or hunger? All one can do is laugh.

The movie’s title is a kind of sick joke. Kubi means “head.” Beheadings dot the film, another instance of Kitano’s interest in sudden, horrific violence. One peasant character spends the entire runtime trying to find a dead samurai to behead so that he can, like Hideyoshi, transcend his class. He’s smart enough to know he can’t take a living one. Thinking himself cunning, he tries to behead a dead ally, only for his superiors to laugh at his folly. You think one of our guy’s heads counts? Try again. Such go jokes in Hideyoshi’s camp.

The final shot of the film involves (not to give too much away) a severed head getting kicked directly into the camera while the, uh, kicker announces the ridiculousness of all this business. Who cares if we have the head? Sure, they can be used for identifying a dead enemy. Or for honor or something. But we know he’s dead; we’re looking at these things for fun! Earlier in the film and setting the tone for this last scene, an honorable samurai commits seppuku on a boat, only for his head to tumble into the water because he realizes, with his short sword deep in his own guts, that he has been betrayed. His retainer jumps in screaming “my lord! My lord!” Hideyoshi chuckles.

On the one hand, there’s a classic resonance here. Alexander and the pirate, Augustine’s states as bands of thieves. War is a bloodthirsty business, and the great men we venerate are as often venal little monsters bent on little more than gratifying their own desires. We are ants to them. And yet, there’s a troubling undercurrent apparent in Kubi. Isn’t it reassuring, almost a pleasure, to imagine that they laugh?

Our leaders being cynical psychopaths affords a certain comfort. Isn’t that the root of Trump’s “I’m grifting; we both know it” routine? Picturing Hideyoshi laughing as he outsmarts the serious Mitsuhide expresses a desire for human leaders, warlords who, yes, are bloody, but who can exist at an ironic remove. They know they’re ridiculous. That puts them in on the joke, as it does us. We’re brought together in this way, smiling amidst the smoldering ruins. Our leaders, I fear, are rarely so jovial; they refuse to admit their own cynicism, perhaps even to themselves. They are all seriousness and ratiocination. They are Decision-Makers. Kitano’s refusal of this grim reality makes Kubi a comedy above all else, which is great as far as these things go. Right now, I could use a laugh.