Source: Wikimedia

Public Domain

War is one of our favorite abstractions. I grew up playing map-based strategy games, the kind in which you pick seneschals, set tax policy, and send figurine-stand-ins off to their deaths. How many divisions does the pope have? How long are my supply lines? Yes, I’d like to enslave the population after we take the city. We need the labor.

No one likes to think about the families annihilated or the sex crimes, the long nights spent in fear and the distant sound of explosions. Worse, when we do consider war in any detail, we find it ineluctably exciting. I love a movie with good squibs. My ears perk up at the sound of a marching drum. Half my generation lost itself in the Call of Duty games (2003-Present). The next has yet to escape Fortnite (2017).

Shoot-and-cries get us only part of the way to making war concrete. They give us the emotional toll, but they do nothing about the killing itself. Implicitly, it remains justified. The enemy remains faceless. The only real thing about war is its psychological aftermath and even then only on our countrymen.

War can only be known to those who experience it. The war reporter remains an observer. What is it like to have your whole world torn away? Everyone you love risks death. Your next meal could come from anywhere or nowhere. They have guns; you likely do not. And, if you choose to pick up a gun, your family and friends have become even bigger targets than they were before. What sort of person do you become? Who are you?

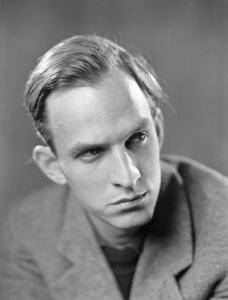

Ingmar Bergman’s Shame (1968) comes about as close as I’ve yet seen to inhabiting and exploring these questions in a way that never glamorizes or glorifies armed conflict. Jan (Max von Sydow) and Eva (Liv Ullmann) Rosenberg are former violinists who have moved from the capital to an island, in part to find peace but more importantly because of the constant risk of war. The Cold War most obviously comes to mind as Bergman’s inspiration. But that’s what makes Shame so powerful: the sides here are meaningless, the places made up. War is war.

Shame, then, is a study in the effects of conflict. No one cares that these two used to be artists. No one cares if they’re just trying to keep their heads down.

Ironically, the potential for conflict seems to hold them together. It gives them something to talk about, a conversational ball to toss around and a measuring stick by which to make sense of their future (Eva wants children before she’s 30). War’s possibility titillates, even inspires. The real thing degrades.

Shame is the simple story of the couple’s transformation, their slow breaking apart under the weight of constant terror. Bergman, in his usual way, still finds room for comedy here (think of the doctor in the internment camp or the propaganda film). How else to survive the most trying of times? But the film’s tone is mostly dour, a sad reflection on the inhumanity of war, its propensity for reducing us to barbarism.

Does that make it an “anti-war” film? I’d say so. By concentrating on a relationship rather than a conflict, Bergman keeps the humanity of his characters front and center. In this way, he avoids abstraction, forces the viewer to imagine themselves amid war, degraded, clawing, reduced.