Source: Flickr user 九间

License

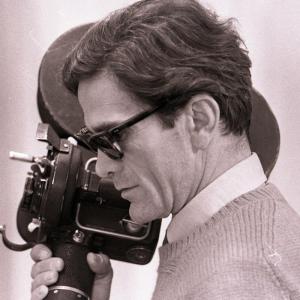

Salò, or the Circles of Hell

During a break from a graduate seminar, I once expressed an interest in watching Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). My professor snickered nervously. It’s not that I wasn’t aware of its reputation. I knew to expect graphic violence, constant nudity, and general perversion. But I have never been one for moralism in filmmaking. As long the film wasn’t merely exploitative, what was there to laugh at or avoid? Ironically, Pasolini’s film is one of the most moralistic—one of the most effective in its didacticism—that I’ve ever seen.

The movie follows a mass of nigh anonymous boys and girls as they are systematically selected, captured, and transported to a mansion somewhere in the fascist Italian rump state based at Salò. Once inside, they are manhandled by a group of fascist paramilitaries, soldiers, and four eminent leaders—all older men, each disgusting in their own way. The President (Aldo Viletti) is cross eyed and constantly cracks obscene jokes. The Duke (Paolo Bonacalli) wears a carapace-like beard and drones on about how fascism is the anarchy of power, the only true way to rule. These men subject the teens to acts too graphic for this sort of public blog post. But imagine what might have made my professor raise an eyebrow. Now double the intensity.

Libertine Impulses

In the world of the manor, chaos reigns. That is by our standards anyway. The four rulers bark orders and promulgate strict rules. The teens will get naked, bark like dogs, and eat scraps or their names will go in a book and they will be punished. Each day everyone will gather in the “orgy room” or “justice” will be meted out. In these ways, Pasolini takes the hedonistic pleasures of the Marquis de Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage (1785; 1904), which praises libertine impulses and reveals them as extensions of fascist dominance.

Desire to Dominate

Above all, this insight shines forth and is (for lack of a better term) the “point” in watching something so unabashedly depraved. Most often, we imagine fascism as at best a lurid form of extreme conservatism, one filled with repression and a kind of eugenicist dedication to sexual fecundity. But this was not true of the actual Nazis [see The Damned (1969) or Madame Kitty (1976)], nor is true of many authoritarian dictatorships (that’s what all the jeweled palaces and fancy clothes are about, after all). The desire to dominate is itself libidinal. Control is never far from pleasure. Aristotle’s tyrant is a slave to his own desire.

Powerless and Alone

Pasolini saves the film from its own potential excesses by restraining his camera. He never holds for that long. Anyone looking for prurience or fascination will not find it here. We see just enough to be disgusted, but his camera never lingers. When we cannot take it anymore, he cuts. Naked people become nothing more than bare, vulnerable commodities—they are not sexually interesting or even really “naked” in our typical meaning [“The naked and the nude / (By lexicographers construed / As synonyms that should express / the same deficiency of dress / Or shelter”)]. This world stands on consumption. Bare skin is just another way to feel powerless and alone.

Reduced to Mere Engines

Indeed, Pasolini suggests that we continue to live under the dominance of such modes of consumption. Even if Mussolini is gone, our rulers and way of being remain, he seems to think, perverse. People are bodies made for consumption—sexually, physically, economically, psychologically. Our leaders—whether the overt offenders like Epstein or more monetarily avaricious like Elon Musk—lord themselves over vast populations of nobodies. There is no obvious way to resist. We’re naked and afraid, locked in the mansion with a gang of perverts. Worst of all, even we, the writhing masses, find ourselves reduced to mere engines of further consumption. Such is life under this cycle of predation.

Pasolini also hated television, among many other things. He died three weeks before the film was released, murdered by mafiosi/fascist thugs. In this film, the victims appeal to Christ and Mary. The fascists appeal to naked power and sexual gratification. Pasolini was an atheist. So was the Marquis de Sade. Make of that what you will. We’re not done with Salò yet.