What could this title even mean? In our day and age, “the medieval” is most often made to confront modernity. That’s when Catholics were Catholic, when Protestants didn’t even exist. By contrast, socialism is a modern pan-heresy that exalts the State over and above everything else. The pairing seems unthinkable.

And yet, it’s not, according to Fr. Bede Jarrett, O.P. In 1914, he wrote a book entitled Medieval Socialism. I’ve been reading it, and, while it’s filled with some of the prejudices you might expect from an early-twentieth century British Dominican (he, for example, thinks that English revolutionaries were reasonable moderates, not like the French and Italians!), it’s also a lucid challenge to so much of what passes for Christian political theology in 2019.

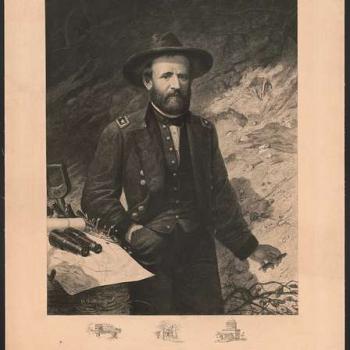

Fr. Jarrett wasn’t much of a radical; he was no Fr. Herbert McCabe or Terry Eagleton. The first Dominican to study at Oxford since the Reformation, he helped found Blackfriars at that same university and became a prior at the age of 33. Fr. Jarrett spent most of his life writing books (after receiving a lectorate in theology) and administering the order. He was so successful and well liked, in fact, that he was the English provincial for the Dominicans from 1914 until his death in 1934—meaning he was elected to the position three times! Authoring such books as The Abiding Presence of the Holy Ghost in the Soul, Our Lady of Lourdes: Meditations on the Salve Regina, and Purity, he wasn’t exactly Shelby Spong or even Gustavo Gutiérrez. Pictures, I’d say, make him look like lawful-good Oscar Wilde, swathed in the robes of a black friar, apparently, advocating (and here is the surprise) socialism.

The book is mostly a historical survey. Jarrett examines how medieval theorists of various sorts thought about property, most specifically private property. He draws on early communists (like the Fraticelli, though including orthodox monastics), the schoolmen (centrally Aquinas), the lawyers (e.g. Bracton and Innocent IV), and many others in order to investigate why and how private property became an absolute and inalienable right, as it has now.

He starts, however, with the obvious question: how can these terms even go together? The very first sentence cuts to the chase:

The title of this book may not unnaturally provoke suspicion. After all, howsoever we define it, socialism is a modern thing, and dependent almost wholly on modern conditions. It is an economic theory which has been evolved under pressure of circumstances which are admittedly of no very long standing. How then, it may be asked, is it possible to find any real correspondence between theories of old time and those which have grown out of present-day conditions of life? Surely whatever analogy may be drawn between them must be based on likenesses which cannot be more than superficial. (Medieval Socialism 9).

But, Jarrett says, the issue is not so simple. Times change. The material conditions in society do not remain the same; these help to determine how we organize ourselves. This idea is actually controversial among many Christians today, who date capitalism to the beginning of time, and who argue that, if truth is “objective,” then its manifestations can never change [his rejoinder: “Man’s life differs, yet are the categories which mould his ideas eternally the same” (Medieval Socialism 11)]. On this point, Jarrett’s dry, direct, English prose requires quotation:

For with man’s life, social, political, or economic, we are in contact with forces which are of necessity always in a state of flux. For example, the predominance of agriculture, or of manufacture, or of commerce in the life of the social group must materially alter the attitude of the statesman who is responsible for its fortunes; and the progress of the nation from one to another stage of her development often entails (by altering from one class to another the dominant position of power) the complete reversal of her traditional maxims of government. Human life is not static, but dynamic. Hence the theories weaved round it must themselves be subject to the law of continuous development. (Medieval Socialism 10)