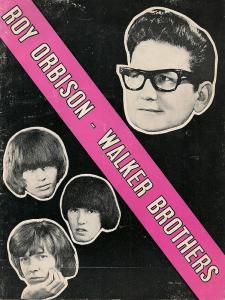

Source: Flickr user, Bradford Timeline

It was about 10 years ago that, driving a friend of mine to some late-night Jersey diner, he told me he was going to queue up something, the likes of which I had never heard before—Bisch Bosch (2012) by Scott Walker. He was right. As best I can recall, he led with “SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter).” Shrieks and instruments I could not place pierced a stochastic silence, all whirling around the near monotone of a male voice, a steady, unaffected baritone belting away:

This is my job,

I don’t come around and put out

your red light when you work.[Silence]

What’s the matter,

didn’t you get enough attention at home?

[Silence]

If sh*t were music,

you’d be a brass band.[Silence]

Know what?

You should get an agent,

why sit in the dark

handling yourself.For Lavinia

who goes like

gynozoon.IX I V

IX III V I

What was this? And who made it? Surely not the then-governor of Wisconsin. I am not typically one for self-consciously theoretical music or otherwise innovative ways of making and recording sound. My formal musical training is limited to a few days trying the trumpet before I was 10, a brief stint as a self-taught bassist (first group eliminated in the Battle of the Bands—woo hoo!), and a love of poetry. My favorite band is probably Korn! Yet somehow, I felt compelled to pursue Walker, to get to know and understand this enigmatic composer. Over the next decade I occasionally revisited his oeuvre, especially these late avant-garde songs (if that’s even the word). It’s only very recently, however, that I finally pieced together something like the whole story, a journey capped off by the discovery of the only feature-length documentary about the man, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man (2006).

The film is a bit of a disappointment, at least as the crowning achievement of my long investigation. With David Bowie, who was inspired by Walker and covered a couple of his songs, on as a producer, I assumed the movie would balance the personal and the musical, develop a connection between the two, even perhaps finally explain the American expat’s bizarre career trajectory (more on that below). Unfortunately, it never quite achieves that balance. It seems as if the filmmakers didn’t know whether this was a tale for the uninitiated or the already obsessed (most viewers were likely the latter, knowing Scott Walker fans). Interviews with the artist himself are laconic and take up very little time at all. I was left with the impression that I’d learned less about his person and vision from hearing Walker talk than I had from his inscrutable music—not because Walker wasn’t articulate in that way that so often seems to afflict artists of all stripes. Rather, my disappointment came from the questions asked, a hodgepodge of biographical queries and occasional thematic points. The choices seemed random, disjointed (even if tied to the chronology of Walker’s career). Show me the full, unedited interview and we can get talking. If the curation is lacking, then let me take what I seek from the whole.

We rehearse his major “periods” and meet some of the people who helped keep his music alive and inspiring during a more-than-a-decade break from releasing his art. Their stories paint a fascinating picture of early-80s punks repackaging 60s pop tunes because the artistry was so apparent, but no one in the scene wanted to be caught dead listening to kitsch. But even in these otherwise involving stories, the descriptions remain the same: Scott Walker was enigmatic. He did his own thing. He stretched music past the point at which it breaks and snaps back, rubber-band-like, and whips into the stars. All true. But, if the documentary is for the fans, get into the nitty-gritty. Interpret a song; create a stable narrative, a kind of line regression that lets us say something about Walker besides the obvious—that he was an enigmatic musician of immense talent who fell prey to his own singular vision.

The camera placement leaves something to be desired too; it underscores the discomforting feelings marinating in my gut during (some of) the interviews. See, for example, this bonus interview from the HMW limited release DVD; it is representative of the other ones included. We’re uncomfortably close to a quarter-profile Walker, who, shot so, seems bereft of anything related to the 1960s teenage heartthrob. At times, I thought of This Is Spinal Tap (1984). If the goal was to mirror Walker’s oddness with an askew and too-close camera angle, it misses the mark and lands in quasi-comedic territory. The good news, however, is that few, if any, of the other interviews are so distractingly presented.

At bottom, the documentary needs to decide what it is and who it’s for. Is it a formalist investigation of the man, built of strange angles that mirror Walker’s own music, a project not unlike Where In the Hell Is the Lavender House? (2019)? Is the movie for fans? Is it an introduction to this artist’s life, accessible to anyone?

I can recommend it if you fit in that last category (as, well, anyone does). It’s a solid primer and introduces his many different sorts of song in a way that makes you somewhat comfortable with the jerks and shifts. You won’t come away feeling like you know the guy’s soul, but perhaps you’ll feel happy to have expanded your artistic experience, been introduced to a new and particular mind. And the Walker fans, well, even if this isn’t really for them (us), they (we) will watch it anyway, simply because there’s so little out there on the man’s life and work.

I did, however, promise his story as best as I’ve come to understand it. My own commentary represents my ruminations on the material (much less often and much less fruitfully than for many others), that is, signifies an attempt to put meat on the bones left by 30 Century Man.

Scott Walker was born Noel Scott Engel in Hamilton, Ohio on January 9th, 1943. Eventually moving with his mother to California, the future popstar got his start in Broadway musicals and on 50s rock-and-roll LPs. On these recordings, his voice hasn’t yet broken, which makes for jarring listening when you’re used to his distinctive baritone. In 1964, however, his path changed. He began working with John Maus, a friend with whom he had previously shared a stage. Maus used the alias “Johnny Walker” to allow him to drink while performing underage in bars. Soon they added a third (Gary Leeds) and a whirlwind blew up.

They made their way to the UK where they exploded, a sort of reverse British Invasion, presenting itself just as the Beatles crossed the other way. With two hit singles and, according to Walker, concerts filled with screaming female fans who barely heard their performances, they were on top of the world. Walker, the singer, became a teen idol, the Harry Styles or K-Pop lead of his day, bigger even than the Beatles (in the UK anyway).

But the music was standard fare. Why go all out if the shrieking kids barely listen? The songs hold up in my opinion on account of the production and vocals (an example: “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore”). By 1967, our subject left the band, apparently packing off to a monastery to learn Gregorian Chant, unsure what to do next.

The cinephile Walker expected to find a more cultured audience across the Atlantic. His love for Bergman, Fellini, and Bresson convinced him that “popular cinema” in Europe was another animal altogether. Finding he was oh-so wrong, he drifted a bit until a Playboy bunny (and possible girlfriend?) introduced him to French chanson master Jacques Brel. The troubadour’s emotive performance style and strange blend of earnestness and irony, suffering and comedy, defined the early solo Walker. 1967 saw the release of Scott, an album largely composed of Brel covers. One exception, however, is “Montague Terrace (in Blue),” an ear-popping track that presaged Walker’s solo talent. Composed sparsely with angelic flutters just tinged with sorrow, the verses lure you in. The chorus arrives with a bang, shattering the previously dainty background music with a wall of sound (in both the technical and general senses) so stark that I swear I can hear a metal trash can getting hit with a bat à la Slipknot. All this as Walker belts out a simple, elegant chorus: “And we know, don’t we? / But we’ll dream, won’t we / Of Montague Terrace in blue?”

Up through 1969’s Scott IV, Walker began including more and more of his own compositions, garnering hits and seemingly building a substantial, if less frenzy-attracting, solo legacy. A problem arose, however: Scott IV flopped. What else could one expect from an album whose first track is a retelling of The Seventh Seal (1957) set to nigh Spaghetti Western instrumentation? He was clearly moving away from pop in an unwelcome way. The age of the hippy had arrived, supplanting the pop ballads of a sullen, pensive Walker.

Aside from (according to most) a 1970 mediocre concept album about the people who dwell in an apartment building, the artist’s releases became increasingly erratic. What did come out, like 1972’s The Moviegoer (entirely made up of covers of film themes), saw limited releases and a reception so poor (in his own view) that Walker disowned them and tried to have all copies destroyed.

Then came 1978, when a reunion with his old bandmates produced an entirely new sound. Knowing they were done, the Walker Brothers did whatever they wanted, breaking up the writing into sections, giving each member a place to express himself. The first four tracks were written by Scott and introduce an electronic music-fueled darkness presented with distorted vocals at a breakneck pace. Listen, for example, to “Fat Mama Kick”:

Sunfighters locked in right angle rooms

Watch their lovers sleep face down in the yellow light

Keep the balance on a back curve

‘Til the war with the night is overThe gods are gone, the air is thick

You cannot risk the fat fat mama kickArmed angels walk the city lights

Wait inside their master corpses peeled raw, betrayed

And fade and fade

As the noise goes over and overThe gods are gone, the searchlights lick

You cannot risk the fat fat mama kick

This is the album, released over a dozen years after his initial success, that would inspire the punks to look back at the singer’s career, ashamed to be drawn to a popstar.

Once again, the man entered occultation, emerging for one album in the 80s, a less-dynamic, more atmospheric extension of his last effort, suffused with the exciting new electronic sounds of that decade. Another ten plus years passed, after which his writing would shoot off into a world all its own.

1995’s Tilt introduces Walker’s “mature” sound. Gone is typical instrumentation and presentation. Gone is any affected, melodramatic singing style. Gone is the semi-coherence of his earlier lyrics in favor of encryption denser than even that of Nite Flights (1978), the album noted above. Subject matter includes Pier Paolo Pasolini’s relationship to a younger man, including tidbits of his poetry, and a transposing of excerpts from the adultery investigation into Queen Caroline into the Adolf Eichmann trial. The beginning of the song invoking regal misdeeds and national socialism, “The Cockfighter,” gets at the heart of this metamorphosis. Tearing sounds, distant screeches, and an unplaceable pitter patter introduce and then underlie a howling voice:

No, no, not my heart

Not the wrist! Not my heart!

Gone somewhere in there

I see the hairline, waking down—aroo!!!

There’s brushing along my legs

All sperm, God’s son

Click-click

Clickety, clickIt’s a beautiful night, oh yes!

From here to those stars

Feathers on the sides of my fingers

Beautiful night, oh yes!

From here to those trembling stars

And the feathers so fresh and the nerves so freshDo you swear the breastbone was bare?

I saw it, and made my escape!

Do you have any doubt he slept in that bed?

I can only repeat, I never saw him

Better listen, before you fly all over your man

You better listen, before I spill you in

If you could turn on your side, move your touch to the hip

Easy now, easy now

It’s a beautiful night

Garcia, a cigarette for the prisoner

His last several albums, including Bisch Bosch, fit this mold, getting sparser and sparser, introducing stranger instrumentation (like punching a slab of meat in a song about the hanging of Mussolini and his mistress, or fart sounds undergirding a track). Scott Walker died in 2019 at age 76, still mostly remembered as a 60s popstar, half-forgotten even by his obsessed (and now old) fans. Underground, his followers trudged on, bolstered by the outspoken support of bands like Bauhaus.

But that’s just the barebones story. I promised to connect the dots with verve. My reflections have brought me to the view that Scott Walker was a man lucky enough to pursue his dreams. His initial fame and success meant the overpowering focus on being famous that so afflicts us (now more than ever) meant nothing to him. How few people can say they became famous beyond their 15 minutes and then got to return to the shadows? This success also meant a stable foundation for his life (possibly supplemented by family money). As a result, he could take his time, fill gaps with the occasional film scoring job, and ultimately do as he pleased.

Trite as it sounds, art is always someone’s expression; even a basic pop tune drafted by a disinterested, even cynical, committee represents and extends some effort, suggests the human spirit dirty and gnarled though it may be. Scott Walker’s early career allowed him to search out the fullest audible expression of his feelings about himself and the world, decades of glum distance instantiated in a language as yet unknown. This question pushed the artist further and further. In a way, he remained (though apparently personable and cheery) that young man who came to Europe to find himself and his taste as much an outlier as back home. There is a disappointment, a darkness, that rings through his music, only intensifying as it gets more abstract and formalistic.

This feeling of desperation began to exceed the bounds of standard songwriting, beyond the pop strictures of the Walker Brothers, the lively expression of Jacques Brel, and even the haunting, halting first step in this direction, Nite Flights. It crashed through standard instrumentation, becoming more concrete (farting, punching, shrieking) and more atmospheric and conceptual (long silences, monotonous intonation, inscrutable lyrics, absurd shifts). His preferred avenue of lyrical expression became a kind of free association. So, “Jesse,” a song ostensibly about the twin Elvis absorbed in the womb also invokes the abandoned 29-storey Sterick Building in Memphis and the destroyed World Trade Center. A haunting chorus locates these homologies in the realm of a deep, breathy, delicate, yet somehow panicked, sadness:

Famine is a tall, tall tower

A building left in the night

Jesse, are you listening?

It casts its ruins in shadows

Under Memphis moonlight

Jesse are you listening?

Like his work or hate it, the central point is that he followed through into the dark corners of a mutually constituting pair: his psyche and our world. Walker felt he had to go beyond what we think of as “music” to do it. Even if a failure, that’s spectacular, a testament to what human beings can accomplish when our needs are met and a desire for fame lies far off. If only 30 Century Man had told that story.