A White Boy Who Did Not Understand

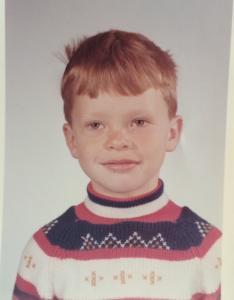

It has only been a few years ago that I came to realize the depths of the secret world of segregation in my beloved small hometown of Lebanon, Virginia. Despite this world of segregation, I LOVED growing up in Lebanon! And I remember having so much fun as a child, and all I wanted to do was play and make many friends.

Forbidden Friendships

I learned later that some friendships were discouraged and, in some cases, forbidden. These forbidden friendships were between white people and people of color.

There was a socially acceptable cap on how close these friendships could be. As a child, I had a loving mom who crossed those lines of Segregation and took me with her.

But as a socially accepted Southern boy, growing up white blinded me to the deep segregation around me. But I learned early on that a deep racial divide existed. Some ignored it. Others accepted the status quo. Some were naive to its existence.

Don’t Call Us Racists.

As a young adult, when I thought of growing up white in the Segregated South, certain images came to mind. Images of KKK rallies in Mississippi, bus boycotts in Birmingham, and the Bloody March from Selma to Montgomery. I grew up believing that Lebanon was not like those horrible places. The racism was, however, much more subtle; nonetheless, you could see it if you had the ability to look at it a little closer.

After experiencing the social pressure of racism at age 7 for becoming friends with a black student in the second grade and watching my mother courageously defend our friendship with our neighbors and my second-grade teacher back in 1969; It began to slowly dawn on me, not all was right in my world.

As an innocent seven-year-old boy, I discovered the unseen divide of segregation in my town. I was born a child of white privilege. And I was beneficiary of a systemic racist American society that in those days treated little white boys and girls very differently from black children. Exposing The Myth of White Privilege

Taking A Closer Look

So how did I start looking a little bit closer to discover the hidden racism in my beloved town? In 2016 -2017 I conducted several interviews for my upcoming book called Hidden Racists: The Dirty Little Secrets of Southern Fundamentalist Christianity. This book focuses on dealing with racism as an evangelical minister in the churches I pastored in Virginia and North Carolina for 18 years. See my blog Confessions of A Recovering Evangelical Pastor.

My journey to becoming a minister started in Lebanon when I was 14 years old. So at age 54, after being a pastor for 18 years and a peacemaker for 16 years, I thought it was time to tell my story. I interviewed African Americans from my hometown who had lived there all their lives. What I learned was both disturbing and a wake-up call. I began to hear about an unseen reality beyond my white privileged world when I was a child.

The World I Discovered

I learned about a world and narrative that was never discussed around most white dinner tables or taught in school. Remember, the integration of the public schools in Lebanon was beginning in 1969. My world would never be the same again. I have no doubt the transition was smoother in Lebanon than in other parts of the South. Why? Because the African American population was smaller than their white counterparts. Nevertheless, there was still pain and fear among our African American brothers and sisters.

I loved my childhood even though I was a bit of a wild child before becoming a follower of Jesus, and my family had their own personal struggles. Lebanon will always hold a special place in my heart, and who knows, one day, I might move back to those hills of my childhood that I love and remember so well. I was loved, nurtured, and accepted in my community. Lebanon, in many ways, reminds me of Mayberry. But there was a darker story, and I experienced it.

In Honor and Memory

I believe many white people in our town were unaware of the painful depths of the racial exclusion of its small African American community. The beautiful people of color lived quietly and kept to themselves in Lebanon before and during the Civil Rights Movement.

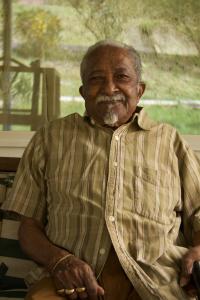

I honor and pay homage to the African American community in Lebanon by attempting to tell a small bit of their story from my perspective. In particular, I honor Mr. James Hicks. His kindness, love, and playful spirit are a testimony to me that we can all overcome and live full lives despite our difficult circumstances.

To that end, I want to share with you four shocking revelations of growing up white in the segregated South.

1st Revelation: I Thought I Lived In Paradise

Lebanon is a beautiful idyllic Southern town nestled in the

green foothills of Southwest Virginia. Back in the ‘60s and ‘70s, we had a bustling population of two thousand people. In the last fifty years, it has exploded to thirty-five hundred people. We are slowly catching up with Chicago.

As a little boy, I wanted to be outside more than I wanted to be inside. We didn’t have computer games, internet, cable TV, or Xbox to occupy our time and distract us; we were almost always outside except for having to come home reluctantly to eat, bathe and sleep.

The Game Master!

My house and yard were Grand Central Station for most of the kids in my neighborhood. Kids were always hanging out at my house because I was the game master. I was always inventing games to play or giving direction to what we would be playing for our time together; Wiffle ball, sword fighting with sticks, and using the trash can lids as shields. Catching lightning bugs when the sun went down in Mason jars, werewolf (my own invention), lost trail, hide and seek, and so much more. These games were on my list as staple activities for every boy in my neighborhood, including a few girls, dogs, and cats to mix.

I remember that my mom would often tell me to be home by supper time. I got so caught up with being in the forest with my friends, playing in our makeshift clubhouse, and letting my imagination run wild that it was long past dusk before I realized I needed to get home. It would not be until the sunset that the magical enchantment of being in the forest would suddenly let me go. It was like I was under some deep spell until the darkness fell. Then I knew I was in big trouble.

When Darkness Falls

Sometimes I would get lost in play with my friends in the woods for six or seven hours at a time. My mom gave me a lot of

freedom as a child, but there were two rules that I had to abide by, or her wrath would come upon me. 1) Be home before dark. I could usually go back and play outside after dark, but I had to be close to home. 2) Always let me know where you will be; especially, if I were in the forest or somewhere else for a long time.

I remember times making my way home from the forest in the dark. I would see flashlights coming in my direction; sometimes, it would be a family friend or my mom and my older brother Gary looking for me.

On a couple of occasions, my mom even had the police looking for me if I were particularly late getting home. I remember getting the spanking of my young life by my mother, and as she was spanking me, she would threaten to ground me for five

years! Thank God her wrath usually passed quickly, and she never kept the five-year grounding sentence she put on me. I eventually learned that I would get grounded whenever I violated her two rules and put in bed early. Often I got a spanking for getting home too late and forgetting to tell my mother where I was.

I remember one particular time seeing a police officer at the end of the flashlight coming towards me. I was climbing a fence separating a cow pasture and the gravel road I needed to get onto to go home. The officer said something like, “Boy, you better got home fast. Your mamma is so upset, and she has the town police out looking for you. You are in a heap of trouble.” I was terrified. It seemed like I was always in trouble, but I sure did have a good time.

Call Me Tom Sawyer

I lived a “Tom Sawyer” kind of existence. Frequent cane pole fishing, swimming in Mr. Calambach’s pond with my best friends and my fat little beagle Hood Doo. My dog actually taught me how to swim. I mimicked her dog paddling, and then nature took its course. It was a wondrous childhood in so many ways, especially if you were white.

2nd Revelation: I Learned Paradise Was Lost To People of Color

Curfew & Shades of Color

As I conducted my interviews with several African Americans in Lebanon, I began to see a new world. I learned that in this idyllic Southern town, my friend James Hicks (who was 93-year-old at the time of the interview ) could not even walk into the doctor’s office with his wife. Why? Because he was a dark-skinned black man and she was a very light-skinned black woman. James shared how African Americans were expected to be off the streets at 6:00 PM. They had to be back in their homes or neighborhood. There were serious consequences if you were black and violated this unwritten curfew.

He remembers one night in particular when some of his friends chose to hang out at Calvin’s corner (a shaded outside bench overlooking Mainstreet). Locals would sit on the corner during the day and white people socialized after the “curfew.” The violation of curfew led to an unpleasant fistfight with some local white residents. The white residents believed Mr. Hick’s friends should not be there at that time.

Unspoken Lines of Apartheid

In my town, African Americans could not walk up Main Street and through the white neighborhoods to visit their relatives and friends who lived on the other end of town. They had to walk a dirt trail in the woods near Quillen’s Hill that ran behind the town and linked Hick’s Circle to Church Street to visit their friends and kin safely.

This was the safest and most acceptable way for people from one black neighborhood to visit the other in Lebanon. A time or two, a few black folks decided to walk through the town and the white residential area to visit their friends. It did not go well for them. I was told white people beat them. Apparently, there were specific times and protocols for when African Americans were permitted to visit each other or come into town.

In my town that Mr. Hicks’ daughter Nancy Foster told me that she can still remember as a child seeing a huge burning cross on a hill that overlooked their neighborhood. She remembers her mother being afraid and telling her to get back in the house. Obviously, there were local Klansmen. These men wanted to frighten and intimidate the small black community in Lebanon and remind them to stay in their place.

No Singing Please

In my town, some young black girls were warned and threatened not to sing in public, “We Shall Over Come.” Black people in Lebanon were expected to step to the side of the sidewalks to let their White neighbors pass by. Black people could not eat in restaurants or sit at the local soda fountain at the drug store with white people.

You Have Your School & We Have Ours

Until recently, I did not even know that just a couple hundred yards from my house were a small schoolhouse on Church Street that African American children had to attend during Segregation. There was even a separate newspaper for the African American community in Lebanon called “The Colored News.”

In my town, Thelma House, now in her 90’s, taught at the small schoolhouse for black children during Segregation. When the racial Integration of Lebanon’s public schools began, the small schoolhouse was closed permanently. And she was transferred to the white elementary school to teach special education for thirty years. She was deeply loved and respected by all who knew her.

At the request of a local school administrator, she was asked to pick up his eight-year-old son each day on her way to school and drop him off. Yet, when she saw the boy’s father in public, he refused to shake her hand in the presence of other white men.

As I interviewed her, she told me she had no bitterness in her heart and that most white people in Lebanon were kind to her, and that her peers at the school were supportive of her as a teacher. She believes that things have definitely changed for the better despite the painful challenges of the Civil Rights Movement and the Desegregation of public schools.

A Long Way From Home

Mrs. Jennie Lee Mabry, another African American senior citizen in Lebanon, remembers how she had to leave the small schoolhouse for black students in Lebanon when she entered the eighth grade to continue her education. She had to go live in a boarding school in Dante, Virginia, which was over 30 miles away, to attend an all-black school. Jennie was not permitted to attend the school that was near her home in Lebanon. Why? Because black children were not permitted to be in the same room with white children. She had to be away from her family for days and weeks. Jennie said the hardest part was that she deeply missed her father.

The Long Journey of School Desegregation

It is important to keep in mind that the Supreme Court declared the segregation of schools unconstitutional on May 17, 1954. The case they ruled on was Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka, Kansas. It would take 62 years before every school was desegrated in the U.S. School Integration In The U.S. Why did the desegregation of the public schools take so long? Because it was a long, slow, and socially difficult process. Several Southern states resisted to the bitter end.

In Virginia, where I grew up, the desegregation of schools began on February 2nd, 1959. It continued until the 1970s when the state’s government finally got tired of the fighting and resisting the desegregation of schools.

In 1969 LC and I experienced the death heaves of the old tired monster of school segregation in Virginia. We did not know it at the time, but we celebrated the final death throws in our state with our lasting friendship. The Desegregation of Virginia Schools

It is hard to believe that the last dying gasp of the desegregation of public schools did not take place until 2016 at Cleveland High School in Cleveland, Mississippi. The Last Segregated School In Virginia

It upsets me when white people say there is no systemic racism in America or that people of color are still not denied their full rights and protections promised to them by the Constitution and the Supreme Court’s rulings. The journey has been long, but we cannot let up now.

3rd Revelation: I Lived In A Town With Two Different Realities

This was my town; Dual realities running parallel to each other, delicately co-existing and intersecting each other with clear rules of engagement and guidelines as to how white and black people would relate to each other when they had to do so.

As a child of white privilege, Lebanon was a paradise on earth, but just a few hundred yards from my house existed an entirely different universe. A world of segregation where black people were expected to keep in their place; and share in a citizenry where they were second-class citizens. I would see black people in our town, but I never understood the wall of segregation between us.

This was a hidden world from my childhood eyes until the day I met my childhood best friend Lawrence Mabry (LC), who just happened to be black. I first met LC in the second grade. In time our friendship would pull back the curtain that would expose that ugly wall of separation.

4th Revelation: I Experienced the Winds of Hope and Freedom

Martin Changed Everything

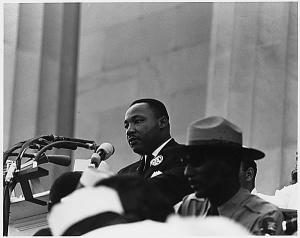

Parallel to this time, the Civil Rights movement was taking place. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated the year before I met LC. Even still, The winds of hope and freedom King inspired were blowing all across the country.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a prophetic luminary of social justice, non-violent resistance, unconditional love, and reconciliation. He inspired a generation to dream of a world where all races would cooperate with God and each other to build a just society. This new society was known as a Beloved Community. The foundation of this community was based on “loving your neighbor as yourself.”

The Winds Blew Into Lebanon

Those winds of hope and freedom had blown into the little town of Lebanon, Virginia. And nobody would be the same again.

Mr. Hicks’s daughter Florence had the wonderful privilege of working with Martin Luther King Jr. for two years. She remembers those years as times of great joy and hope. She said that Martin was a kind, playful, and good man. He always connected with the people who worked with him and was so approachable. It was such a treasure to find Florence and meet someone from the black community in Lebanon who actually knew Martin Luther King Jr. in such a special way.

The winds of hope had blown into Lebanon, and nothing would be the same again. My little town was not a violent racist town like some of these you see in movies such as Mississippi Burning, The Star Chamber, or The Ghosts of Mississippi. Lebanon was probably more like the movie Driving Miss Daisy. There were small acts or moments of violence accented over much longer periods of time. But not on the same level and magnitude of the big horrific stories in other parts of the South.

Although Lebanon did not have the deep ongoing acts of violent prejudice and oppression like the deep South or in the Northern cities such as Chicago, yet its evil poisonous tentacles reached all the way to our little town and negatively impacted the lives of our black neighbors.

Second Class Citizens

As I conducted my interviews with members of the African American community in Lebanon, it became clear that they had to learn how to cope with living as second-class citizens. When I heard their stories, I asked them how they could find pleasure or joy in life under Segregation. They knew they had to wake up every day to such frustrating and hopeless realities. Nearly every one of them would smile at me and say, “We had to learn to let it roll off of us like water on ducks back.”

I still cannot fathom the deep courage and positive self-encouragement that many of these precious folks had to do every to face the harsh realities of Segregation. I do not think I could have been so brave. The people I interviewed had a strong and deep faith in a God who restores justice to the land. They knew that one day, freedom would come.

White Fragility

Some White people in our area may deny there was ever a significant racial division in our town. Maybe they did not see it, or worse, refused to see it. As white people, we have to work a little harder and put ourselves in the shoes of our black neighbors. We need to do this to understand the deep pain and trauma they have endured. Why It Is So Hard To Talk About Racism

Currently, the church I attend is predominantly white. We spent over a year educating ourselves on white privilege and systemic racism. Our journey led our small group to a ceremony of lament and repentance as we discovered the historical racial sins committed by our white relatives and ancestors. We were shocked how much U.S. history has sanitized the stories and persecution of all people of color. Also, we came to realize that we were beneficiaries of the white privileged society they helped create for us.

Things Have Changed

As I began to research my book, I found that all I had to do was start asking black people in Lebanon questions about the days of Segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and their struggle for freedom and equality during Integration. The result of those interviews was that a new world quickly began to emerge for me. My African American friends lived in a world of white privilege that for much of their lives was underneath the surface.

Not so long ago, in this little beautiful town that I loved so much, black people were expected to stay in their place. Their place was clearly defined both socially and geographically. But as Thelma House said, “Things have definitely changed for the better.” What Would Martin Luther King Jr. Say In January of 2021?

Forbidden Friendships

As I said before, all of this prejudice was unseen by me as a child until I met LC, my first black friend. We met in the second grade in 1969. Unfortunately for some people, our friendship was a forbidden one.

It was my mother who advocated for us and strengthened our friendship. She saved me from racism. She stood up to this terrible social system with courage, a smile, and generous hospitality to all she knew. Color did not keep her from making friends outside her race, religious beliefs, or economic status. All were welcome in our home. Much of the man I am today, I owe to her. I will share her story in my next blog.

I Welcome Your Comments

Any thoughts or personal experiences on what it means to grow up white or black in the Segregated South? Or the big cities of the Northern Segregation? Why do you think so many white people are uncomfortable facing the historical pain and trauma of people of color? Any thoughts on what needs to change? What are you doing to fulfill Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream for the world?

I’d love to hear your comments!

I am a full-time peacemaker in the way of Jesus. Also, I am a Life Coach, avid bodyboarder, oceanophile, YouTube Influencer, and father of an amazing 14-year-old daughter. I love to write and try to make the world a better place.

As a peacemaker, I focus on peace and social justice activism and bridge-building between Muslims and Christians.

If you’d like to get to know me better, please follow me on social media.

My Blog: http://www.jeffburns.org

FaceBook: https://www.facebook.com/jeffrey.r.burns.1

FaceBook (Peace Page): https://www.facebook.com/IFollowThePath

Instagram: @themysticbodyboarder

Twitter: @PeaceJourney

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/c/JeffBurnsThePath

Until next time.