In Defense of Priest-Penitent Privilege

*Bibliography at the end of the article.

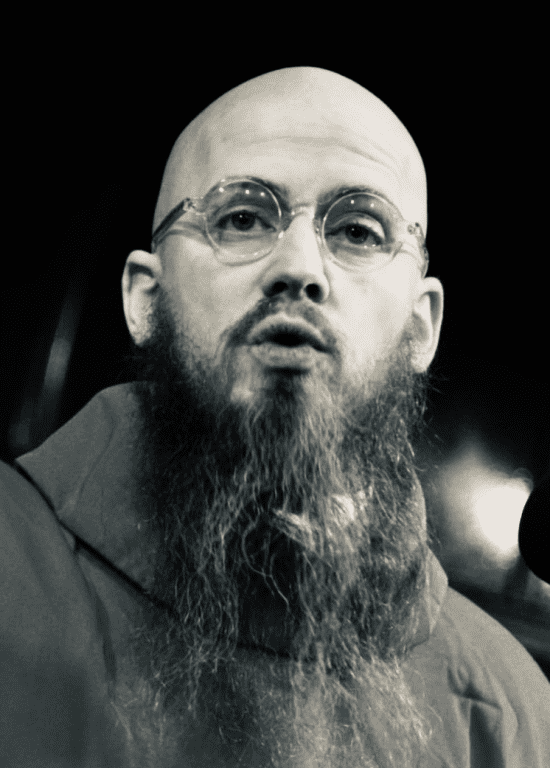

Death row represents the ultimate moral, spiritual and ethical crucible. Inmates in extremely confined spaces daily face the final reckoning of their lives. Yet, even in the shadow of execution…fundamental rights and moral duties endure. Central to this is priest-penitent privilege…the inviolable protection of confidential communications between a priest (spiritual advisor) and penitent. For those condemned to die, such interactions are essential for moral reflection, reconciliation with God among others and preparation for death.

Priest-penitent privilege sits at the intersection of theology, morality, practicality, ethics and law.

Roman Catholic canon law mandates the absolute inviolability of the confessional seal (Canon 983 §1, 1983), a standard also followed by Old Catholic bishops who also emphasize freedom of conscience and pastoral autonomy (Utrecht Declaration, 1889). Eastern Orthodox theology frames confession as a spiritual encounter in which the priest acts as a healer of the soul (John Chrysostom, On the Priesthood, 4.9). These three traditions combine to speak widely to the historical teachings of Christianity.

Priest-penitent privilege serves a profound moral purpose. By ensuring confidentiality, it allows inmates to confront guilt honestly, engage in true ethical reflection and seek reconciliation with both God and others. This moral safeguard preserves human dignity and agency, a principle recognized not only in domestic law but also in international human rights standards. For example, Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948), which affirms the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Privilege between a priest and penitent enables death row inmates to approach the end of life with integrity, remorse and the possibility of spiritual restoration.

Legally, confidentiality is protected under Federal Rule of Evidence 501, as interpreted alongside constitutional guarantees under the First Amendment, Equal Protection Clause and statutory protections such as the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA, 42 U.S.C. §2000cc-1(a)). RLUIPA explicitly safeguards the religious exercise of institutionalized persons, including death row inmates…prohibiting substantial burdens unless justified by a compelling state interest pursued in the least restrictive means.

The protection of priest-penitent communications has long been reinforced through legal precedent. Early 19th-century cases, including People v. Phillips (1813) and People v. Smith (1817), recognized that compelling disclosure would undermine both moral accountability and societal interests…affirming the sacred and confidential nature of confession. In modern contexts, federal courts and statutory frameworks continue this protection…Mockaitis v. Harcleroad (1997) upheld clergy privilege even in capital cases…while Ramirez v. Collier (2022) extended these principles to executions, ensuring that final sacramental rites are legally safeguarded. Together, these cases create a continuous line of authority demonstrating that priest-penitent communications are inviolable, providing death row inmates with essential protection for spiritual guidance, moral reconciliation and the exercise of conscience. This essay argues that priest-penitent privilege is essential on death row.

By integrating moral, theological and legal reasoning, it demonstrates that confidentiality in spiritual counseling preserves human dignity, moral agency and religious liberty even at the point of death.

Theological Foundations of Priest-Penitent Privilege

Roman Catholic Perspective

In Roman Catholic theology, confession is a sacramental encounter by which the penitent reconciles with God. The priest acts in persona Christi, facilitating repentance and spiritual healing (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1993, §1467). Canon 983 §1 affirms: “The sacramental seal is inviolable; therefore, it is absolutely forbidden for a confessor to betray in any way a penitent” (Code of Canon Law, 1983).

Breaking this seal would not only violate canon law but would deprive the penitent of moral agency and the opportunity for genuine repentance. Confidentiality ensures that the condemned can confront guilt honestly, reconcile internally with victims and approach death with spiritual integrity. Morally, the seal enables inmates to engage in true ethical reflection, accept responsibility and seek reconciliation with God and humanity.

Further, the Catholic theological framework asserts that sacramental confession is an encounter with divine mercy and the priest serves as a conduit of grace. The penitent’s honest articulation of sin…paired with the priest’s guidance…allows for both moral and spiritual restoration. On death row, where the stakes are ultimate and irretrievable. The sacramental encounter provides a critical avenue for facing past wrongdoing and confronting mortality.

Old Catholic Perspective

The Old Catholic Church, in addition to regularly following the Roman canon, also emphasizes freedom of conscience. The Utrecht Declaration (1889) asserts that confession must be approached freely, without coercion from church or state. This aligns with moral and legal reasoning…the state cannot impose on the penitent’s religious exercise without violating conscience, ethics and statutory protections.

For inmates, Old Catholic priests provide a confidential space in which repentance is free from fear of civil or institutional reprisal. Ethical guidance is paired with the assurance of confidentiality…enabling penitents to engage in honest self-reflection and moral reckoning. The Old Catholic perspective complements Roman practice by highlighting conscience as a moral touchstone…ensuring that penitents’ engagement with God remains uncompromised by external pressures.

Old Catholic theology is also informed by Eastern Orthodox tradition of priests serving as moral and spiritual guides.

Eastern Orthodox Perspective

Eastern Orthodox theology portrays confession as spiritual therapy. St. John Chrysostom stresses that betrayal of a penitent’s trust harms both the individual and the Church (On the Priesthood, 4.9). Orthodox canon law emphasizes confidentiality as a mechanism for moral and spiritual healing (Guidelines for Clergy, 6 (Orthodox Church in America, 1998)) (Statute of the Russian Orthodox Church (as adopted by the Jubilee Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, August 2000).

A death row inmate revealing decades of violent conduct and deep remorse relies on confidential guidance to achieve moral clarity and spiritual reconciliation. Breach of this confidentiality would cause profound moral harm, demonstrating the convergence of ethical, theological and legal imperatives. Orthodox teaching also emphasizes the therapeutic aspect of confession, guiding penitents toward ethical realignment, preparation for death, and restoration of spiritual balance…critical outcomes for those facing execution.

Ethical and Human Rights Foundations of Priest-Penitent Privilege

Denying priest-penitent privilege fundamentally undermines human dignity, moral agency and the ability of condemned inmates to engage in reconciliation. Even individuals facing execution retain fundamental human rights under both domestic law and international law. The First Amendment guarantees freedom of religion (U.S. Const. amend. I), and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment ensures all inmates are treated equitably under the law (Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319, 1972; Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 1987). These protections are complemented by international standards, particularly Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which affirms the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, including the right to practice one’s faith both publicly and privately (UDHR, 1948). Compelling spiritual advisors (priests/clergy) to disclose confessions or limiting confidential spiritual counseling reduces inmates to mere objects of punishment, depriving them of the moral agency that underpins repentance and reconciliation (Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022)).

Priest-penitent privilege fosters authentic moral reflection. Inmates assured of confidentiality are more likely to fully disclose past wrongs, confront the consequences of their actions and articulate genuine remorse. Confession provides a structured framework for ethical introspection, enabling penitents to align conscience with both divine moral law and societal ethical norms (Canon Law Society of America, 1983; Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1993, §1467). Confidentiality ensures that this process is unhindered by fear of state intrusion…supporting both spiritual reconciliation and internalized ethical accountability.

Clergy, too, bear ethical responsibilities that are protected by privilege. Without legal recognition, priests risk moral compromise if compelled to violate the confessional seal…undermining both canon law and theological mandates. Protecting confidentiality allows clergy to provide spiritual guidance faithfully and to uphold moral integrity…even under the pressures inherent in death row contexts (Utrecht Declaration, 1889; Chrysostom, On the Priesthood, 4.9). Here, ethical, legal and theological reasoning converge…safeguarding the seal protects both the conscience of the penitent and the integrity of the confessor.

The ethical imperative extends to society as a whole. Confidential sacramental reconciliation encourages acknowledgment of wrongdoing, moral reflection and contrition…even among those condemned for severe crimes. By facilitating genuine ethical engagement, society indirectly fosters moral rehabilitation and reinforces recognition of human dignity (UDHR, 1948; Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319, 1972). Such engagement also reinforces broader societal norms around accountability, forgiveness and ethical responsibility…demonstrating that the protection of religious exercise benefits both individuals and the moral fabric of the community.

From a practical perspective, priest-penitent privilege supports psychological, spiritual and ethical well-being. Inmates who can confess honestly and receive absolution often experience reduced anxiety, greater emotional stability and a stronger capacity for ethical reflection. Even imminent execution does not diminish the significance of these practices…they provide moral closure, mitigate despair and enable inmates to confront their final accountability in accordance with conscience (Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022); Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1993, §1467).

Legal recognition of priest-penitent privilege is therefore both a moral and human rights obligation. It ensures that inmates can engage in final acts of repentance and moral reconciliation, while clergy are able to minister without coercion. Privilege represents a unique intersection of religious liberty, ethical responsibility and human rights, affirming the inherent worth of every human being, including those condemned to death. By protecting this confidentiality, society demonstrates respect for conscience, religious freedom and universal human dignity…aligning domestic legal protections with international human rights standards (UDHR, 1948; RLUIPA, 42 U.S.C. §2000cc-1(a), 2000).

Practical Examples of Priest-Penitent Privilege on Death Row

Confidential spiritual guidance is critical. Inmates confront fear, guilt and existential despair. Priest-penitent interactions allow them to confront these realities and move forward with moral closure. Consider these examples…

Reconciliation with Family

A condemned inmate estranged from his children sought moral reconciliation. In private confession, he recounted past neglect and abuse of loved ones. The priest provided absolution, declaring that God forgives sins through the sacrament of reconciliation when the penitent demonstrates sincere contrition and resolution to amend their life. Over several sessions, the priest guided him to articulate remorse and prepare letters of apology. Though he was prohibited from sending the letters by his attorneys (who were afraid that it might influence his final appeals), the sacramental act of confession allowed the inmate to confront guilt and achieve internal peace. Confidentiality was essential…without it…he would have withheld truth…denying himself the grace of spiritual reconciliation.

Confronting Past Violence

Another inmate…guilty of multiple violent crimes…faced fear of divine judgment. Through confession, he recounted each act of violence and its moral consequences. The priest instructed him in penance, provided counsel and granted forgiveness, emphasizing that God’s pardon is available to those who repent sincerely. The sacramental experience allowed the inmate to feel morally reconciled and spiritually prepared for death. Without the inviolability of the confessional seal…he might have concealed truths in fear that others (maybe even family) might find out and judge him for…depriving himself of moral and spiritual restoration.

Emotional Healing and Moral Preparation

An inmate experiencing severe anxiety about execution engaged in repeated sessions of confession and spiritual reflection. Each session involved examining conscience, confessing sins, performing penance and receiving absolution, which provided profound moral relief. The priest guided him to reconcile with his conscience, accept responsibility and achieve spiritual readiness. Confidentiality allowed full honesty, ethical growth and reconciliation with both God and self.

Reconciliation with Victims’ Families

A condemned inmate sought to reconcile spiritually with victims’ families. Through confession, he admitted wrongdoing and expressed remorse. The priest guided him in spiritual penance and pronounced forgiveness, affirming God’s absolution. Even though he was not allowed direct contact with victims’ families by law, the sacramental encounter allowed the inmate to experience profound moral and spiritual closure without harming anyone else.

Spiritual Guidance at Execution

In a situation akin to Ramirez v. Collier, a condemned individual requested his pastor’s presence during execution. The inmate received final confession and absolution, verbally recounting sins, acknowledging remorse and accepting responsibility. The priest prayed aloud, laid hands on him and pronounced forgiveness. The Supreme Court recognized such spiritual guidance as protected under RLUIPA, highlighting that confidential sacramental acts are legally safeguarded and morally necessary (Ramirez v. Collier, 2022).

The examples are limitless. Confidentiality and spirituality are by their nature intimately intertwined. Priest-penitent privilege is necessary for any remotely spiritual society to function.

Legal Foundations of Priest-Penitent Privilege

The protection of priest-penitent privilege on death row is deeply rooted in constitutional principles, particularly the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and is further reinforced by statutory safeguards such as RLUIPA. For incarcerated individuals…including those facing execution…these protections ensure that religious exercise is not subordinated to administrative convenience or penal objectives.

First Amendment Protections

The First Amendment guarantees the free exercise of religion, prohibiting the government from interfering with an individual’s right to practice faith (U.S. Const. amend. I). For prisoners, this includes access to religious counsel and confidential communication with clergy (Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319, 1972). The Supreme Court has emphasized that incarceration does not eliminate the fundamental right to religious exercise, even under highly controlled or security-sensitive conditions. Confidential spiritual communication is an integral part of faith practice…confession, absolution and pastoral counseling are not merely symbolic but essential for moral and spiritual reconciliation…especially for inmates confronting death (Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319, 1972; Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 2005).

Requiring priests to disclose confessions or limiting access to private spiritual counseling constitutes a substantial burden on religious exercise…undermining the inmate’s ability to practice faith according to conscience. The denial of confidentiality disrupts the moral and ethical dimensions of religious practice…particularly in capital cases, where the opportunity for genuine repentance and spiritual reconciliation is often the last available chance. Courts have repeatedly recognized that even in high-security environments, inmates retain a protected right to confidential interaction with clergy, reflecting the constitutional understanding that faith and conscience are not suspended behind prison walls (Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022)).

The First Amendment also safeguards clergy as intermediaries of moral and spiritual guidance. Forcing a priest to violate the sacramental seal would not only infringe on the inmate’s rights but also impinge on the ministerial freedom of religious advisors, creating a conflict between conscience and state authority (Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319, 1972). By protecting priest-penitent communications, the law ensures that faith practices are respected and clergy are empowered to provide guidance without fear of reprisal, fulfilling both constitutional and theological imperatives.

Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (U.S. Const. amend. XIV) complements First Amendment protections by guaranteeing that all inmates, regardless of faith tradition, have equal access to confidential clergy counseling. This clause prevents arbitrary distinctions that would allow one inmate to receive sacramental guidance while denying it to another based solely on denomination, administrative policy or institutional discretion (Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 1987).

Denying access to priest-penitent communications disproportionately affects faith traditions that rely heavily on sacramental practice…including Catholic, Old Catholic, and Orthodox Christians…as well as other faiths with confidential spiritual guidance rituals. The Equal Protection Clause ensures that institutional rules do not privilege or disadvantage any religious group. This is particularly critical on death row…where unequal access to spiritual guidance can mean the difference between moral and spiritual reconciliation and existential despair. Courts have recognized that failure to provide equitable access to clergy counseling violates both legal and moral imperatives, as it creates unequal treatment of inmates with sincere religious needs (Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 1987; Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022)).

Moreover, the Equal Protection Clause serves to reinforce the First Amendment by requiring that prison regulations are applied consistently. Even if the state asserts a compelling interest in maintaining security or order, those regulations cannot selectively burden one religious practice while accommodating another. In practical terms, this means that a Catholic or Old Catholic or Orthodox inmate must have the same access to confidential spiritual advisement and sacramental guidance as an inmate from any other faith tradition. Ensuring equal access protects both conscience and spiritual integrity…which is especially consequential for inmates confronting the finality of execution (Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319, 1972).

RLUIPA Protections

The Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA, 2000) further strengthens these protections, explicitly forbidding any substantial burden on religious exercise of institutionalized persons unless justified by a compelling government interest applied in the least restrictive manner (42 U.S.C. §2000cc-1(a), 2000). On death row, RLUIPA ensures that inmates’ access to confession and sacramental guidance cannot be denied merely for administrative convenience or institutional policy. The statute codifies the principle that religious exercise…including priest-penitent communication…is a fundamental human and legal right that persists even under the most controlled circumstances.

RLUIPA also highlights the cumulative importance of constitutional and statutory protections. It integrates First Amendment safeguards with practical prison administration by requiring courts to scrutinize any policies that substantially burden religious exercise. In capital cases, where the ability to confess, receive absolution and engage in penance may be the inmate’s last opportunity for moral reconciliation, RLUIPA reinforces both the ethical necessity and legal entitlement of priest-penitent privilege (Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022)).

Synthesis

Together, the First Amendment, Equal Protection Clause and RLUIPA create a robust legal framework ensuring that priest-penitent privilege on death row is protected. The First Amendment guarantees the freedom to practice religion, including confidential spiritual guidance. The Equal Protection Clause ensures that all inmates are treated equally, preventing arbitrary discrimination based on faith. RLUIPA codifies these protections into enforceable statutory law, prohibiting substantial burdens unless absolutely necessary.

In practice, this triad of protections ensures that death row inmates can confess sins and receive forgiveness without fear that their communications will be disclosed. It guarantees that clergy can minister without compromising conscience, preserving the moral and theological integrity of the sacramental encounter. These protections demonstrate that religious liberty and human dignity are paramount, even in the context of the state’s interest in security, order, and capital punishment.

By emphasizing equal access and non-interference, these legal provisions align with both moral imperatives and constitutional mandates. Denial of priest-penitent privilege would violate the First Amendment, undermine the Equal Protection Clause and contravene RLUIPA, stripping inmates of spiritual guidance at the most critical moment of life. Protecting these rights ensures that faith, conscience, and moral agency remain inviolate, even in the shadow of execution.

Legal Precedence for Priest-Penitent Privilege

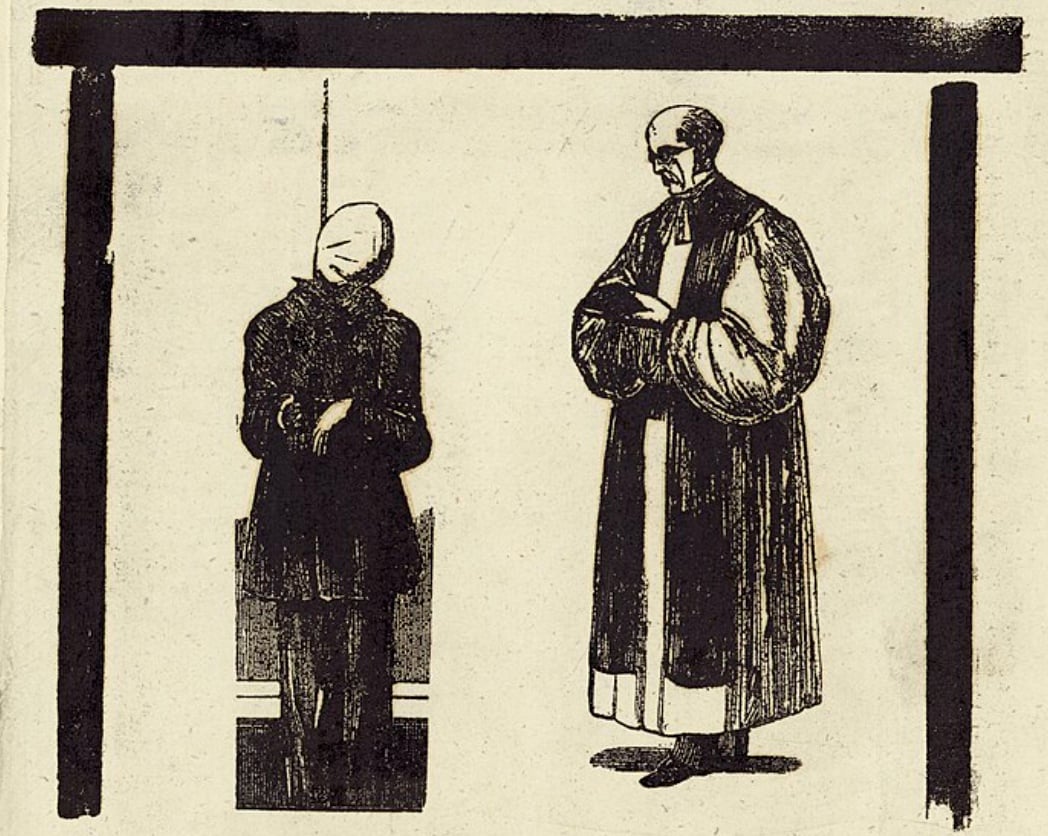

Priest-penitent privilege occupies a unique space, offering protection to communications made during confession. Across centuries and jurisdictions, courts have consistently recognized that these communications are not ordinary speech but sacred encounters, essential to moral reflection, spiritual reconciliation and ethical accountability. For death row inmates, the privilege takes on heightened significance…it safeguards their ability to confront guilt, perform penance and seek absolution without fear of secular reprisal. From early American cases like People v. Phillips (1813) and People v. Smith (1817) to modern federal and Supreme Court rulings such as Mockaitis v. Harcleroad (1997) and Ramirez v. Collier (2022), the legal system has affirmed that confession is protected by law, morality and religious principle. This section examines these precedents, demonstrating that priest-penitent privilege is both legally enforceable and ethically indispensable, particularly for those facing the ultimate sanction of death.

People v. Phillips (New York Supreme Court, 1813)

In People v. Phillips, the New York Supreme Court considered whether a Catholic priest could be compelled to testify regarding a confession made by a defendant accused of theft (People v. Phillips, 1813). The case arose when the prosecution subpoenaed a priest to disclose statements made during confession, aiming to use them as evidence against the defendant. The priest refused, invoking the absolute inviolability of the sacramental seal as recognized in Catholic canon law.

The Court carefully analyzed the nature of confession, emphasizing that it is a sacred encounter between penitent and priest, not merely a private conversation. The court recognized that compelling testimony would chill penitential practice…undermining both the individual’s moral development and broader societal interests in ethical accountability (People v. Phillips, 1813). The decision highlighted the importance of protecting religious conscience, establishing that certain communications cannot be subordinated to procedural demands even in criminal proceedings.

Importantly, Phillips demonstrated an early recognition of the unique moral and theological significance of confession. The court noted that requiring disclosure would discourage penitents from fully confronting wrongdoing…compromising opportunities for repentance and moral restoration. This precedent is particularly relevant to death row inmates, who confront ultimate accountability and rely on confidential confession to seek spiritual reconciliation, perform penance and receive absolution before execution. By protecting priest-penitentcommunications, the court ensured that religious practice could continue unimpeded…preserving both spiritual integrity and societal moral order.

The ruling also implicitly recognized that confession serves more than evidentiary purposes…it is a moral instrument that facilitates internalized justice, ethical reflection and personal transformation. For death row inmates, this aspect is critical…the seal allows them to confront crimes honestly without fear that candid admissions will be used against them, reinforcing the notion that religious liberty intersects directly with moral rehabilitation.

People v. Smith (New York Supreme Court, 1817)

People v. Smith built on the foundation laid in Phillips, clarifying the boundaries of clergy privilege (People v. Smith, 1817). In this case, the defendant had confessed to a serious crime, and the prosecution again attempted to compel the priest to testify. The Court was faced with balancing the needs of justice against the moral and spiritual protection of the confessional.

The Court reaffirmed that confession to clergy is protected, emphasizing that compelling disclosure would not only undermine the penitent’s moral development but also violate societal interests in internalized justice and ethical accountability. The ruling underscored that the law must respect the sanctity of religious exercise…even in cases involving grave offenses…including potential capital crimes (People v. Smith, 1817).

In its reasoning, the Court highlighted that sacramental confidentiality serves both moral and legal ends. Morally, it allows penitents to engage in truthful self-examination, experience contrition and seek forgiveness. Legally, it ensures that the judicial system does not interfere with constitutionally and socially recognized rights to religious practice. For death row inmates, Smith has profound implications…it establishes that even in the most high-stakes circumstances, the state cannot compel disclosure of penitential communications, preserving opportunities for spiritual reconciliation, moral closure and absolution.

The decision also illustrated a nuanced understanding of the role of clergy in society. The Court recognized priests not merely as witnesses but as moral mediators whose guidance has societal and individual importance. In denying the subpoena, the Court affirmed the principle that faith and conscience are protected even when weighed against evidentiary interests, a principle that continues to safeguard spiritual counseling in modern capital punishment contexts.

Cruz v. Beto (1972)

The Supreme Court’s decision in Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319 (1972), is a landmark case for religious freedom in prisons and provides important context for the recognition of priest–penitent privilege. The case involved a Buddhist inmate in Texas who was denied access to a place of worship and prohibited from sharing his religious literature with other prisoners…even as Christian inmates enjoyed full access to chapels and ministers. The Court held that the First Amendment guarantees of religious freedom apply within prisons and that inmates must be given “reasonable opportunities” to exercise their faith comparable to those afforded to adherents of other religions.

The significance of Cruz for priest-penitent privilege lies in its affirmation that incarceration does not extinguish constitutional rights, particularly those rooted in the free exercise of religion. Just as Buddhist inmates must be afforded the opportunity to practice their faith on equal footing with Christians, so too must all inmates be ensured confidential access to clergy for confession and spiritual counsel. The Court’s reasoning underscores that religious practice is not a privilege granted at the discretion of prison authorities…but a fundamental right protected by the Constitution.

Applied to the death penalty context, Cruz v. Beto reinforces that condemned inmates retain the right to sacramental practices, including confession. Denying access to confidential clergy…penitent communication would replicate the constitutional violation at issue in Cruz…favoring state authority over the free exercise rights of inmates. Thus, the case strengthens the claim that priest–penitent privilege must remain inviolate even on death row, protecting the moral and spiritual integrity of the incarcerated at life’s end.

Federal Rule of Evidence 501 (Federal Courts, 1975)

Federal Rule of Evidence 501 provides the modern statutory framework for recognizing privileges…including clergy-penitent privilege…in federal courts (Fed. R. Evid. 501, 1975). The Rule codifies that privileges are governed by common law, interpreted by courts in light of reason and experience. This allows courts to adapt longstanding protections…like the priest-penitent privilege…to contemporary legal challenges, including those involving death row inmates.

The rule emerged to reconcile competing interests…the need for reliable evidence in criminal proceedings and the moral, ethical and religious imperatives that underlie confidential communications. Courts interpreting Rule 501 have emphasized that clergy-penitent communications are fundamentally different from ordinary conversations. They are not made for social convenience or personal benefit but for spiritual formation, repentance and moral realignment (Fed. R. Evid. 501, 1975).

For death row inmates, Rule 501 serves as a crucial safeguard. Confidential confession allows inmates to articulate past wrongs, experience genuine contrition and receive absolution without fear of secular repercussions. The Rule affirms that these communications are legally protected and that any attempt to compel disclosure would constitute a substantial burden on religious exercise, contravening both constitutional and statutory protections.

Additionally, Rule 501 reflects an understanding that clergy-penitent privilege protects the integrity of moral and spiritual guidance. By recognizing the privilege under common law, federal courts acknowledge that sacred communications serve both personal and societal moral interests. This is especially relevant for death row inmates, for whom the opportunity to confess and seek absolution is often their last chance for spiritual reconciliation. Without this legal protection, penitents might conceal sins, undermining both personal moral responsibility and the ethical objectives of justice.

Turner v. Safley (1987)

The Supreme Court’s decision in Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987), established the standard for evaluating prison regulations that burden constitutional rights. The case addressed two issues: restrictions on inmate-to-inmate correspondence and prohibitions on prisoner marriages without warden approval. The Court held that while prisoners do not forfeit all constitutional protections upon incarceration, those rights may be limited by regulations that are “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.” The Turner test thus balances the constitutional rights of inmates against the state’s interest in security, order and administration.

Though not directly about religion, Turner is central to understanding how courts evaluate claims involving priest-penitent privilege in prison. The decision makes clear that any restriction on religious rights must have a reasonable legitimate connection to penological objectives. Generalized fears or administrative inconvenience are insufficient to justify burdening fundamental freedoms.

For death row inmates, Turner means that attempts to restrict confidential access to clergy must withstand exacting scrutiny. A prison cannot deny sacramental confession or compromise its confidentiality simply for administrative ease or speculative security concerns. Instead, prison authorities must show that restrictions are narrowly tailored and truly necessary for safety or order. In practice, this standard has bolstered judicial recognition that confidentiality in confession is not only morally and theologically essential but also constitutionally protected against unwarranted intrusion.

Mockaitis v. Harcleroad (U.S.C.A. 9th Ct, Oregon, 1997)

Mockaitis v. Harcleroad involved a capital murder case in Oregon in which the State sought to compel a Roman Catholic priest to testify regarding a confession made by the defendant, William Mockaitis. The confession took place in private within the prison, following the traditional sacramental format…the inmate disclosed specific acts of criminal conduct, expressed genuine contrition and requested spiritual guidance and absolution. The priest, bound by the sacramental seal, refused to reveal any content of the confession, asserting that disclosure would violate both canon law (Canon 983 §1) and his ethical obligations.

The District Court had to weigh the competing interests…on one side, the state’s interest in fully prosecuting a serious criminal offense…on the other, the penitent’s constitutional and religious rights. The court engaged in an exhaustive analysis, recognizing that the penitent-priest relationship is not merely confidential but sacred, serving a moral and spiritual purpose essential to human conscience. The court observed that compelling testimony could undermine the penitent’s ability to engage fully in moral reconciliation…thus inflicting irreparable spiritual and ethical harm.

The court’s ruling emphasized several key principles. It affirmed that the priest-penitent privilege is not conditional on the gravity of the crime or the public interest in prosecution. Even in capital cases, the moral and theological imperatives of sacramental confession cannot be discarded. Compelling testimony would force clergy to violate a fundamental moral and spiritual duty…creating a direct ethical conflict between obedience to civil authority and adherence to sacred law. The court also noted that forcing disclosure could erode public confidence in religious institutions. If penitents feared that their confessions could be used against them in court…the confessional would lose its moral efficacy…diminishing society’s access to the moral benefits of spiritual guidance. Finally, the ruling recognizes that for those facing execution, confession and absolution are not auxiliary rites but essential opportunities to confront guilt, seek forgiveness and prepare spiritually for death. Without full confidentiality…penitents may withhold critical moral truths…undermining both the sacramental act and their own moral agency.

Cutter v. Wilkinson (2005)

In Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005), the Supreme Court addressed the scope of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) as it applied to inmates’ religious rights. The case arose when Ohio prisoners who practiced non-mainstream religions…including Wicca, Satanism, and Asatru…claimed they were denied access to religious literature, ceremonial items and group worship opportunities afforded to more conventional faiths. The State argued that enforcing RLUIPA in favor of minority religions violated the Establishment Clause by advancing religion.

The Court unanimously rejected this argument, holding that RLUIPA is a permissible accommodation of religious exercise in institutional settings. Importantly, the Court emphasized that protecting inmates’ rights to practice their faith…even in restrictive prison environments…is consistent with the First Amendment and does not improperly privilege religion. Instead, it ensures that religious freedom is meaningfully preserved, even behind prison walls.

For priest-penitent privilege, Cutter demonstrates that constitutional and statutory protections extend beyond mainstream practices to encompass the deeply personal and sacramental needs of all faith traditions. The ruling affirms that prisons must actively accommodate religious exercise rather than merely avoid overt discrimination. In the context of death row, this precedent underscores that absolute confidentiality in sacramental confession is not a dispensable courtesy but a protected form of religious exercise. Denying such access would directly contravene the constitutional and statutory mandates affirmed in Cutter, undermining both the integrity of religious practice and the moral rights of the condemned.

Ramirez v. Collier (U.S. Supreme Court, 2022)

Ramirez v. Collier represents one of the most significant modern affirmations of religious liberty for death row inmates. In this case, John Henry Ramirez…a Texas death row inmate…requested that his pastor be allowed to lay hands on him and pray aloud during his execution, as part of his final sacramental rites. The State initially denied this request, citing security and procedural concerns. Ramirez’s counsel argued that such denial imposed a substantial burden on his religious exercise under RLUIPA and violated First Amendment protections.

The Supreme Court’s analysis was meticulous and far-reaching. It considered the centrality of religious exercise, emphasizing that the requested pastoral acts…laying on of hands, audible prayer, and final confession…were not ancillary but central to Ramirez’s faith and preparation for death, and that preventing these acts would undermine the very core of his religious practice. It also addressed the substantial burden under RLUIPA, recognizing that RLUIPA prohibits any substantial burden on the religious exercise of institutionalized persons unless justified by a compelling government interest in the least restrictive manner, and that denying Ramirez’s requests placed a direct and substantial burden on his ability to engage in sacred rituals that provide moral clarity, absolution, and reconciliation. The Court further acknowledged the moral and theological significance of these practices, noting that the laying on of hands is a sacramental act that allows the penitent to approach death in alignment with conscience and religious duty, and that denial would interfere with moral agency and spiritual integrity, which the Court recognized as critical even in the final moments of life. Finally, the Court considered the implications for future cases, with Ramirez establishing a precedent that death row inmates’ religious exercise must be respected even in the context of execution procedures, reinforcing priest-penitent privilege and extending protection to ritual acts essential to confession and absolution.

The Court ultimately granted relief, permitting Ramirez’s pastor to perform the requested sacramental acts. In doing so, the ruling highlighted the convergence of constitutional, statutory, and ethical imperatives: RLUIPA, the First Amendment and centuries of moral and theological tradition converge to protect spiritual guidance at the moment of death (Ramirez v. Collier, 2022).

This case underscores several critical points for death row ministry. Confidentiality is essential, as the priest’s role in final confession and absolution cannot be compromised. The moral agency of the penitent is protected, since the condemned retains the right to fully engage in religious practice that reconciles conscience and prepares for death. Institutional obligations must also accommodate faith, meaning that even administrative and security concerns must yield to the compelling interest in religious exercise. Finally, Ramirez integrates with broader legal precedent, aligning modern law with Mockaitis, Phillips, Smith, and federal rules governing clergy privilege, thereby reinforcing the doctrinal and legal continuity of priest-penitent protections.

In effect, Ramirez v. Collier not only safeguards Ramirez’s spiritual rights but also sets a binding standard for the treatment of all death row inmates seeking priestly guidance, ensuring that their final sacramental encounters…including confession and absolution…are legally protected, morally affirmed and spiritually respected.

Synthesis

The jurisprudence surrounding priest-penitent privilege illustrates a consistent commitment to preserving the moral and spiritual integrity of confession. Cases like Phillips and Smith establish foundational protections, affirming that compelling disclosure undermines both personal moral development and societal ethical interests. Federal Rule of Evidence 501 and decisions such as Mockaitis v. Harcleroad further codify these protections, emphasizing that clergy privilege is absolute, even in capital cases. Ramirez v. Collier demonstrates that modern courts continue to uphold these principles, recognizing the profound moral and theological significance of sacramental acts for death row inmates. Collectively, these cases underscore that priest-penitent privilege is not merely a procedural formality but a critical safeguard of conscience, religious liberty, and human dignity. For inmates facing execution, it ensures that their final opportunities for confession, absolution, and reconciliation remain fully protected, honoring both the letter of the law and the deepest moral imperatives of justice.

Religious Liberty, The Sacredness of Confession and Priest-Penitent Privilege

Priest-penitent privilege on death row is morally, theologically and legally indispensable. Catholic, Old Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions converge on the inviolability of confession. Ethical reasoning emphasizes human dignity, moral agency and clergy responsibility. Practical experience demonstrates that confidential spiritual guidance facilitates repentance, reconciliation and emotional preparation for death.

Legally, cases from People v. Phillips (1813) to Ramirez v. Collier (2022), alongside Federal Rule of Evidence 501 and RLUIPA, give evidence of the protection of this privilege across centuries and jurisdictions. First Amendment protections and the Equal Protection Clause further bolster claims that all inmates…regardless of denomination or circumstance…should be able to access confidential clergy guidance.

To deny priest-penitent privilege would subordinate conscience to procedure, strip the condemned of essential spiritual guidance and diminish human dignity at life’s end. Upholding it affirms that faith, conscience and moral agency remain inviolable, even in the shadow of execution.

Religious liberty is not an abstract concept…it is the very lifeline of the soul. On death row, where fear, guilt and mortality converge the freedom to confess, receive absolution and reconcile with God must be protected…because if it is not protected there then it is not protected anywhere. Protecting priest-penitent privilege is therefore not merely legal compliance…it is a profound affirmation that even at the edge of death…the religious practice of every person is sacred, untouchable and inviolable.

Bibliography

- Canon Law Society of America. Code of Canon Law, Latin-English Edition. Washington, D.C.: CLSA, 1983.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. Vatican: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1993.

- Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319 (1972).

- Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709 (2005).

- Declaration of Utrecht. Old Catholic Churches of the Union of Utrecht, 1889.

- Federal Rule of Evidence 501. Pub. L. 93-595, 88 Stat. 1926 (1975), codified at 28 U.S.C. app.

- Guidelines for Clergy. Orthodox Church in America, 1998.

- Mockaitis v. Harcleroad, 938 F. Supp. 1516 (D. Or. 1996), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 104 F.3d 1522 (9th Cir. 1997).

- People v. Phillips. N.Y. Ct. Gen. Sess. 1813. Reprinted in John H. Langbein, The Privilege of the Confessional in Anglo-American Law. University of Chicago, 1991.

- People v. Smith. 2 City Hall Recorder 77 (N.Y. Ct. Gen. Sess. 1817).

- Ramirez v. Collier, 142 S. Ct. 1264 (2022).

- Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA). Pub. L. No. 106-274, 114 Stat. 803, codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000cc et seq.

- Statute of the Russian Orthodox Church. Adopted by the Jubilee Bishops’ Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, August 2000.

- Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987).

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights. G.A. Res. 217 A (III), U.N. Doc. A/810 (1948).