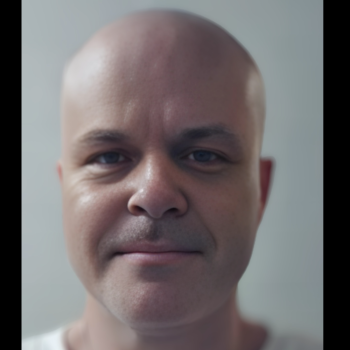

Ronson Bush was raised in Chickasha, Oklahoma, in a tight-knit family. Like most country boys, he has a special bond with his mom. He also has a younger brother and sister he was especially close to. He spent many hours of his childhood on his father’s farm, where he developed a deep love for horses—riding them, training them, and forming the kind of bond that only comes from long hours in the saddle.

His parents eventually divorced, but the relationship was amicable. His mother worked for the county court, and his stepfather was a sheriff’s deputy, giving Ronson a strong sense of structure and community early on. He was especially fond of his grandparents, often gathering around the table for his mom and grandma’s irresistible southern delicacies. Summers included days spent at the lake with his many aunts and uncles, who showered him with love and attention.

As an adult, Ronson was known for being hardworking and determined. He attended auctioneering school and, with his smooth, commanding voice, quickly found success in the field. He also worked long hours hauling freight across Oklahoma and Texas in his truck—work that demanded endurance, focus, and grit. Early on, he married and became a father, a role that brought him immense pride. Though he and his wife were young and the marriage didn’t last, they remained friends and co-parents, keeping a strong connection for the sake of their son.

Like many young men, Ronson enjoyed drinking and having a good time with his friends. But what he didn’t realize then was that the habits that felt harmless were slowly steering him down a darker path. What started as fun began to blur his judgment, leading to a pattern of decisions that would gradually spiral out of his control. Looking at that version of Ronson—the family man, the working man, the boy who loved horses and the road—it’s hard to reconcile with what would one day unfold. But life is rarely a straight line. And somewhere along the way, a mix of pain, addiction, and emotional unraveling began to take root. To understand how it all ended in tragedy, we have to explore the long, complicated path that pulled him further and further from that foundation.

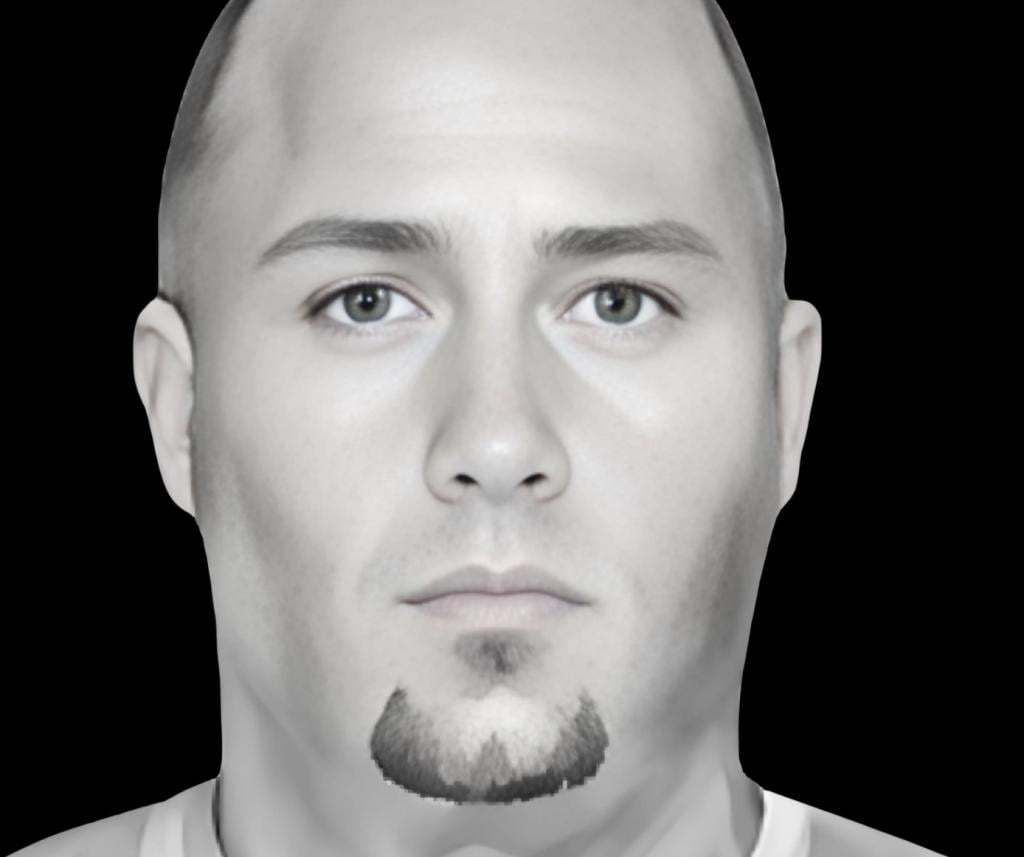

Ronson Bush is now on death row in Oklahoma. His execution date is coming up in March of 2027. On the surface, many may think he deserves to die for what he did. He admits that he killed his best friend, Billy Harrington. His friend did nothing to him that would warrant this violent act. What’s striking is what Ronson says about his state of mind during the murder. He claims he was as shocked by this as anyone else. In his words, it felt as though he had stepped outside of his own body, watching from a distance as the horror unfolded. He recalls seeing the expression on his own face in that moment—blank, with hollow eyes, as if “no one was home.” After his arrest, Ronson broke down in the back of the police car and again in his holding cell, repeating over and over, “I killed my best friend. I can’t believe it. Why would I kill my best friend?” He was so filled with remorse, that when it came time for trial, he stopped proceedings to plead guilty—refusing to drag either Billy’s family or his own through more pain. He didn’t fight the charges. He didn’t ask for mercy. And still, the court sentenced him to death…

Ronson Bush and Billy Harrington were best friends for nearly two decades. By all accounts, Billy did everything that he could to try to help Ronson, and vice versa. However, both young men were stuck in a cycle of drinking and recreational drug use that was beginning to negatively affect their lives. For example, one evening Billy was at a classy event, where he became inebriated and attempted to fight with a security guard. After his arrest, Ronson asked a family friend who was a lawyer to represent Billy. Billy had a young daughter, and Ronson didn’t want to see his friend have to serve time in jail. At the same time, Ronson’s own life was spiraling. His girlfriend, Stephanie, had just found out she was pregnant—but unable to cope with Ronson’s escalating drinking, she had moved out and ended the relationship. Both young men were on the edge, trying to hold each other up, even as the weight of their own struggles pulled them down.

On December 18 of 2008, Billy drove Ronson to Griffin Memorial Hospital in Norman, Oklahoma, where Ronson committed himself for alcohol treatment, in an attempt to get Stephanie to see he wanted to change for her and the baby. Just like he always had been, Billy was there to pick Ronson up when he called four days later. Treatment had not been what he expected, the staff had been filling him up with psychiatric medication, which made him feel weird, and numb. Ronson figured he could control his drinking on his own, or make things up to Stephanie another way. Besides, Christmas was coming, and he didn’t want to miss a holiday with his young son Brennon, from his previous marriage.

Ronson signed himself out, and then he and Billy stopped at Chili’s, where they ate lunch and each drank two lite beers. When they arrived back at Billy’s house, they drank from a bottle of vodka they’d picked up on the way home. In good spirits, Billy and Ronson shot guns, played with Billy’s dog and Billy gave Ronson a haircut. All seemed to be right in the world, until everything changed in one instant. Sometime around 7:15, things went majorly off the rails. Ronson and Billy were talking about Christmas. Ronson told Billy he bought Christmas presents for Stephanie, and his son. Ronson said at that point Billy looked at him and said “Why do you keep wasting your time with a girl like her. She has slept with so many guys, Hell, even I slept with her,” Whether such comments were true or not, one can never know. What is told by Ronson, is that he instantly felt a switch flip in his brain, and although he doesn’t remember doing so, he picked up the revolver he had just been cleaning and shot Billy with it six times.

Ronson remembers going out to the barn later that evening, and seeing Billy laying in the grass. Shocked, but beginning to realize what he had done, he headed to Stephanie’s house. In his disoriented state, he felt he needed her presence, and he hoped she might be able to help him figure out what to do next. She wasn’t home when he arrived, so he let himself in, took a few swigs from a bottle of Crown Royal, and crawled into her bed to sleep. When Stephanie returned, she found him there, asleep in the dark bedroom. She couldn’t turn on the overhead light with the switch. Apparently he was so out of it he had gotten the fan and light mixed up. He woke up and began trying to explain what had happened. In that moment, Ronson seemed so detached, so lost in shock, that he didn’t appear to realize—or care—that he was in the last place he should be. (On a previous drunk and belligerent night, Stephanie had filed a protective order against him, and his presence there violated it). Still, there was no sign that Stephanie was in any immediate danger. In fact, she was able to calmly walk him outside and get him into her car. She then called the police, who arrived shortly after and arrested him. He did not resist.

At the time of his arrest, Ronson tearfully confessed to killing Billy. But he also struggled with finding out that after the shooting, he had tied Billy’s body to the back of his pickup truck and dragged him out into the field where he later stumbled upon him in shock. He had no memory of doing this—and when he was told, he was horrified. The field was just behind Billy’s house, the body was left out in the open, not concealed. It was a senseless, impulsive act—one of many that began after Ronson was released from the hospital and seemed to snowball without logic or intention. Another of those impulsive decisions came during the legal process: Ronson abruptly stopped his trial to enter an Alford Plea—essentially pleading guilty without negotiating any deal through his attorneys. His lawyers took him aside and explained that, had the case gone to trial, there was a strong chance the charge could be reduced to heat-of-passion manslaughter rather than first-degree murder. But by entering the plea, he would be sentenced for murder. Ronson didn’t seem to grasp the consequences. He wasn’t thinking clearly and, in his dazed state, offered himself up to die.

The very next day, however, he tried to reverse the decision. He told the court he wanted to withdraw the plea. But it was too late—the court refused to allow it. As it often happens in a small town, the judge and the DA in the case knew Ronson and his family well. Ronson’s mom and stepdad both worked for the County legal system. Ronson believes he was hated by the DA for previous false and offensive comments he had made about the DA’s wife in order to anger him. Despite the conflicts of interest, Ronson’s defense team never requested a change of venue.

In the beginning, Billy’s family did not want Ronson to face the death penalty. They had known him since he was a boy, and despite the horror of what had happened, they believed his remorse was real. They saw the killing as senseless, but not calculated, and they had no reason to doubt that Ronson was devastated by what he had done. But that all changed when a jailhouse informant named Jacky Nash entered the picture. Nash had shared a cell with Ronson in the county jail while Ronson was awaiting sentencing. Facing felony charges of his own, Nash was eager for a break—hoping to secure a lighter sentence by offering information to the prosecution. He claimed that Ronson had confessed to premeditating Billy’s murder, even going so far as to plant guns at Billy’s house in the days before the killing. Ronson has always insisted that Nash’s claims were complete fabrications. Still, Nash’s statement was submitted in court and read aloud for the judge and Billy’s grieving family to hear. It changed everything.

In response, Billy’s family gave powerful, emotional victim impact statements—this time calling for the harshest possible punishment. And the tone in the courtroom shifted. The judge, who had until then appeared measured, seemed to take a harder stance. Ronson was sentenced to death.

Billy Harrington was Ronson Bush’s best friend. He felt comfortable enough around Ronson to say what he said about Stephanie, even with a gun around, because he believed Ronson would never be violent with him, even in the face of harsh truth. I believe that if not for Ronson’s struggle with alcohol, Billy would still be alive. But alcohol wasn’t the only factor. During that hospital stay, Ronson was prescribed a medication called Celexa. While this antidepressant can be effective for many, it carries serious risks for individuals with undiagnosed bipolar disorder—often triggering mania, paranoia, and distorted thinking. Ronson’s grandfather had bipolar disorder, suggesting a genetic predisposition that was never considered. No one at the hospital diagnosed Ronson with anything before giving him the medication. He was discharged without a formal diagnosis, without a prescription, and without any guidance on how to taper off the drug safely. No one warned him that mixing alcohol with Celexa could dangerously intensify its effects. By the time he left the hospital, Ronson was already in a vulnerable mental state—confused, unstable, and untreated.

Since Ronson and I’s initial conversations, I’ve grown to really love him as a friend. He is smart. He is creative. He is considerate. He is even hopeful. There is no question that Ronson must be held accountable for what happened. A life was lost. But I struggle to see how the death penalty is justice in this case. Had Ronson been in his right mind—had he been properly diagnosed, treated, and informed—Billy would still be alive. In a humane society, someone like Ronson wouldn’t be thrown into a concrete cell to await execution. He’d be receiving treatment—for his mental illness, for the trauma of what he did. Even though Ronson is in prison, his family still needs him. He wanted to stop his trial to save Billy’s family the pain of a long drawn out trial, and ended up destroying his own family in the process. Ronson was given the ultimate punishment. But punishment without care for reform is not justice. It’s barbaric. It doesn’t fix a broken mind. It doesn’t restore a stolen life.