Jalal al-Din Rumi taught, “Ritual prayer can be different in every religion, but belief never changes” (Fihi Ma Fihi). As a Reform Rabbi who has been studying Islam for almost sixty years, I think it is vitally important for our generation to understand how much Islam and Judaism have in common. In North America and the U.K., Jews and Muslims are the two religious groups that most noticeably practice fasting. The rules about fasting are very similar in both Jewish and Muslim law.

Jalal al-Din Rumi taught, “Ritual prayer can be different in every religion, but belief never changes” (Fihi Ma Fihi). As a Reform Rabbi who has been studying Islam for almost sixty years, I think it is vitally important for our generation to understand how much Islam and Judaism have in common. In North America and the U.K., Jews and Muslims are the two religious groups that most noticeably practice fasting. The rules about fasting are very similar in both Jewish and Muslim law.

There are several religious values involved in fasting, and Muslims will see many similarities, and a few differences, in the following restrictions from the Jewish tradition about what and when we eat.

First of all, why should people restrict their culinary pleasures? More outrageous, why should we afflict ourselves by fasting? Isn’t being happy the most important thing? Isn’t eating one of the most accessible pleasures we have?

Why do Islam and Judaism restrict their adherents from the simple pleasure of food each year?

The Torah decrees a day of fasting (Leviticus 16:29, 23:27), Yom Kippur—the Day of Atonement—when for twenty-four hours adult Jews (in good health) are supposed to afflict their souls by abstaining from eating, drinking and marital relations. Also, the 9th of Av (a day of mourning like the Shi’a observance of Ashura- the 10th of Muharram.)

For the entire the month of Ramadan, Muslims fast, also abstaining from food, drink and marital relations, from first light until sundown. The Qur’an says “Oh you who believe! Fasting is prescribed to you as it was prescribed to those before you, that you may (learn) self-restraint” (Qur’an 2:183).

All animals eat, but only humans choose to not eat some foods that are both nutritious and tasty. Some people do not eat meat for religious/ethical reasons. Jews and Muslims do not eat pork for religious/spiritual reasons.

Feeding the Soul Through Fasting

Fasting differs from praying in the same way that hugging someone differs from talking to them. When I fast, I create an empty space in my body that would have been filled with food if I had eaten. This empty space helps me open myself to a personal spiritual experience. Fasting is not magic. It is only an aid to help connect me to my maker. When my belly is full of food, and my life is full of things, I have less room for God. Fasting is very different from starving. People do not choose to starve.

It is one of my religious obligations to help feed starving people. Fasting is my personal opportunity to feed my soul. Fasting results in many different outcomes that help bring us closer to God.

First of all, fasting teaches compassion. It is easy to talk about the world’s problem of hunger. We can feel sorry that millions of people go to bed hungry each day. But not until one can actually feel it in one’s own body is the impact truly there. Compassion based on empathy is much stronger and more consistent than compassion based on pity.

This feeling must lead to action. Fasting is never an end in itself; that’s why it has so many different outcomes. But all the other outcomes are of no real moral value if the fasting does not enlarge and extend compassion.

As the prophet Isaiah said, “The truth is that at the same time you fast, you pursue your own interests and oppress your workers. Your fasting makes you violent, and you quarrel and fight. The kind of fasting I want is this: remove the chains of oppression and the yoke of injustice, and let the oppressed go free. Share your food with the hungry and open your homes to the homeless poor” (Isaiah 58:3-7).

Second, fasting is an exercise in willpower. Most people think they can’t fast because it’s too hard. But actually the discomfort of hunger pangs is relatively minor. A headache, muscle pains from too much exercise, and most certainly a toothache, are all more severe than the pains hunger produces.

The reason it is so hard to fast is because it so easy to break your fast, since food is almost always in easy reach; all you have to do is take a bite. Thus the key to fasting is the willpower to decide again and again not to eat or drink. Our society has increasingly become one of self-indulgence. Almost all humans lack self-discipline.

Fasting goes in direct opposition to our increasing “softness” in life. When people exercise their willpower to fast, they affirm their self-control and celebrate their mastery over themselves. We need continually to prove that we can master ourselves, because we are aware of our frequent failures to be self-disciplined.

Fasting to Prepare to Meet Challenges

Third, fasting is also a way of preparing to meet a major challenge. People in the Bible who faced great trials and troubles often prepared themselves through prayer and fasting. Whenever special courage, wisdom, insight or strength was needed, people who trusted in God turned to prayer and fasting.

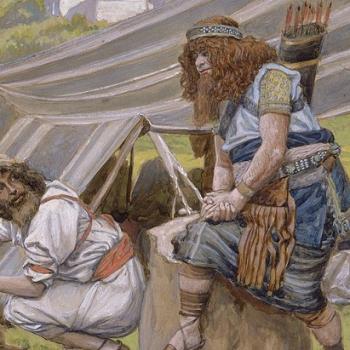

For example, the Jewish community in Persia once was threatened by a government sanctioned pogrom that resulted from a plot by the King’s evil adviser, Haman. This name is well known to Muslims because it occurs six times in the Qur’an (28:6, 8, 38; 29:39; 40:24, 36)

These ayahs portray the Egyptian, Haman, as an official close to Pharaoh, who was in charge of building projects that Banu Israel were forced to work on. The Persian Haman organized groups of his own supporters to attack and plunder Jews throughout the Persian kingdom on the appointed day.

When the plot was leaked, the queen, who was Jewish, although nobody in the court knew it, was asked to intercede. Before Queen Esther approached the king to ask him to spare the Jews from destruction, she asked her people to join her during three days of prayer and fasting.

She felt that this dangerous enterprise needed prayers fortified by fasting if her effort was to be successful. Esther said, “When this is done, I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. And if I perish, I perish” (Esther 4:16). Consequently, Esther approached the king with confidence and boldness, persuading him to reverse an edict that called for the annihilation of the Jews.

Fasting to Improve Health

The fourth outcome of fasting is improved physical health. Prolonged and regular fasting promotes health. A single twenty-four-hour fast, and even a one-month sunrise-to-sunset fast, will not have any more effect than one day or one month of exercise. But the annual fast on Yom Kippur can awaken us to the importance of “how much and how often we eat.” As people age, their intestinal stem cells begin to lose the ability to regenerate. These stem cells are the source for all new intestinal cells, so this decline can make it more difficult to recover from gastrointestinal infections or other conditions that affect the intestine. This age-related loss of stem cell function can be reversed by fasting, according to a 2018 study from MIT biologists. The researchers found that fasting dramatically improves stem cells’ ability to regenerate, in both aged and young mice.

More important, since our society has problems with overabundance, fasting provides a good lesson in the virtue of denial. Health problems caused by overeating are the most rapidly growing health problems in affluent Western countries. Thus going without all food and drink, even water, for a twenty-four-hour period challenges us to think about the benefits of the very important religious teaching: less is more. Or as the Talmud states, “Grab it all, you won’t grab it at all: but if you grasp a little, you can hold on to it” (Rosh HaShanah 4b).

Fifth in our list of outcomes; fasting is a positive struggle against our dependencies. We live in a consumer society. We are constantly bombarded by advertising telling us that we must have this or that to be healthy, happy, popular or wise.

By fasting we assert that we need not be totally dependent on external things, even such essentials as food. If our most basic need for food and drink can be suspended for twenty-four hours, how much more our needs for all the nonessentials. In our overheated consumer society, it is necessary periodically to turn off the constant pressure to consume, and remind ourselves forcefully that “man does not live by bread alone.” (Deuteronomy 8:3)