By Noah Lawrence

“God bless you, my man,” the airport security official said to me.

I had just walked out of the full-body scanner, where I had put my hands above my head, waited, and undergone the metallic, robotic swipe. The first official I saw outside the chamber told me her colleague needed to pat down my arms. He did. Now he was blessing me.

He patted me on the shoulder, his face and voice smiling yet sad, sad yet smiling. He was an African-American man with a bushy salt and pepper mustache. He said these words at the precise moment when, usually, the official giving me a pat-down asks to pat down my kippah, or yarmulke. It was two days after the shooting at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Congregation.

“Thank you — you too,” I said. How do you prepare for an airport security official’s blessing you? I had only instinct: gratitude for his words, thrumming with small holiness and spontaneous fellowship; and a sense that blessing is for everyone, so as he offered it to me, I wanted to offer it to him.

He leaned his mouth to my ear and said, “You know, I hated that incident.” He said so much in saying so little. Elementary school teachers caution that “hate is a strong word.” His use of the term satisfied their criterion. As FDR might say if he were president today (and would that he were), we have nothing to hate but hate itself.

“Thank you. That means so much to me,” I said. What could I add to express specific solidarity with him as an African-American, as he had with me as a Jewish-American? Should I mention the Charleston shooting? But that happened some time ago, and I wanted to be sure not to accidentally objectify him. So I said, “We’re all brothers and sisters, right?”

He leaned his ear to my mouth. The intimacy of speaking into someone’s ear, of hearing someone speak into yours, is not something one shares with everyone. I repeated what I said, and he said, simply, an affirmative “Mm-hmm.”

I re-pocketed my 21st century clutter, picked up my bags, and — the man now in conversation with another security official — walked off toward the escalator, toward a flight from Detroit to New York City.

What did it mean that an airport security official had just wished me God’s blessing? I once heard Rabbi Nehemia Polenof the Boston area’s Hebrew College give aclass in which he grappled with how to define the word, “bless.” He examined the Priestly Blessing in the Book of Numbers:

May the Lord bless you and guard you.

May the Lord light up His face to you and grant grace to you;

May the Lord lift up His face to you and give you peace.

(Numbers 6; all translations from Robert Alter’s translations except where indicated)

Why the emphasis on face? Why no material promises? Rabbi Polen concluded that the core of the act of blessing is to see someone; in this vast cosmos, to acknowledge someone; in this too-often-lonely world, to express to someone, “I recognize your personhood.” So God does for us, and so we can do, or not do, for each other.

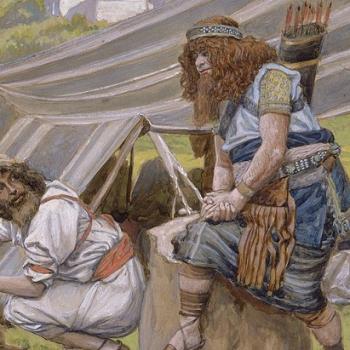

By that definition, this airport security official had surely blessed me. He had truly seen me; I felt seen. I felt, specifically, that he had seen me as a “na’ar,” a Hebrew word Robert Alter renders as “lad,” and that fathers in the Hebrew Bible frequently use for sons. (Even when King David’s son Absalom is leading an armed insurrection, David tells his commanders, “Deal gently for me with the lad Absalom” (2 Samuel 18:5).)

Tenderness and affection percolated inside me like a frosty morning’s coffee.

***

Moments like this one kept happening. As I stood in line at a coffee shop, a man said to me, “Ma shlomcha?” — the formal Hebrew expression for, “How are you?” and one that literally means: “How is your peace?” “Baruch Hashem, b’seder gamur. V’ata?” I responded — “Blessed be the Name, okay, completely. And you?” All these words and phrases are idiomatic, ordinary, in modern Hebrew. But — and this feature is the language’s most precious — the words contain within them deep ancient wellsprings, and amid the events of these times, those springs’ waters rose. “Baruch Hashem, b’seder gamur,”he said in return, smiling, adding, “That’s all the Hebrew I know.”

He and I talked so much that he almost forgot to order. He shared with me that he was searching for a way to bring more Jewish tradition into his life, but he wasn’t sure where to start. I shared with him that someone once asked the Lubavitcher Rebbe, “What’s the most important mitzvah in the Torah?” and the Lubavitcher Rebbe answered, “The next one that you do.” I asked my newfound friend if he liked to read, he said yes, and I suggested three of my favorite entry points into Judaism: the School of Hebrew at the Middlebury Language Schools, offering a way to understand Jewish prayer services; The Sabbath, a classic of modern Jewish spirituality, by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel; and Robert Alter’s translations of the Hebrew Bible, with their as-literal-as-is-feasible English and insightful, wide-ranging commentaries.

As we parted ways, he said, without mentioning the massacre, “I feel better now.” I said, “I do too.”

Once I boarded the plane and sat down, I saw a woman two rows ahead, an African-American woman about 40 years old, struggling to jam her bag into the overhead bin. I asked her, “Do you want some help with that?” As I spoke, a man under the bin reached his hand up and pushed on the bag; it fit.

“That is so good of you!” she said to me, her voice rising, eyes flashing, smile sun-wide. “Let me give you a hug.” And she gave me a hug. The other man said, “I don’t get a hug?” She gave him a hug too.

“That was so kind,” I said to her. She said to me, “No, that was so kind.”

***

Partially, these stories are about what it’s like to wear a kippah, being identifiable as Jewish by sight. But I wear a kippah every day, and other days are not like this one. Partially, this story is about kindness among strangers. But I try to offer people help with their bags as often as I can, and none of them has ever hugged me. Nor did the woman who hugged me plan on hugging the man who ultimately helped her.

People are seeing me differently today, I thought. In that moment, I saw myself differently. People are seeing me as vulnerable. I saw how vulnerable I was. I realized that by putting on a kippah that morning, I had taken my life in my hands. The events of the past week testify that this viscera-twisting fact is now part of life in Trump’s America — as has been true for Jews of numberless epochs, from Moses amid the bulrushes to my grandfather who survived the pogroms; and as is true for too many people of too many backgrounds, from President Obama, George Soros, and those who work at CNN, to African-Americans in Kentucky, and all who could be in their shoes. (I wrote an op-ed about the more socio-political dimension of the recent violence in The New York Daily News on October 31, published here.)

People saw me differently — and they reached out their hands, literally, in kindness. I reached out in return. We fought for those moments, like cavemen scraping stones furiously to spark flame. We fought for them, and we won, reliving Jacob’s wrestling and seeking to live by the name his divine challenger spoke: “Not Jacob shall your name hence be said, but Israel, for you have striven with God and men, and won out” (Genesis 32:29).

In the Talmud, Rabbi Yitzhak quotes Rabbi Yohanan’s statement, “Jacob our forefather did not die,” and adds, “Just as his seed is alive, so is he alive” (Babylonian Talmud, Volume Ta’anit (Fast Days) 5b, my translation). On that day at the Detroit airport, we shared those moments of kindness precisely because of the loss of the victims, and thus in their memory. By doing so, we were in spirit their seed. As we lived, so did they. In the presence we shared, we kept their presences alive in this world. We gave them “a memorial and a name,” in the words of the Book of Isaiah (56:5 — from this verse the Israeli Holocaust memorial and museum Yad Vashemtakes its name).

I felt, in our shared kindness and presence, a deep light, a light we created amid darkness. We helped God to fulfill the line from the Jewish evening prayer service: “Blessed are You, Lord … Who creates day and night, Who rolls away light before darkness … ” — that is the part that we, and God, wish humans would not do; that is the part that “grieved [God] to the heart” (Genesis 6:6) — followed by the part that God needs our help to do: “ … and [Who rolls away] darkness before light.”

The cast of characters in these stories is significant: a Black man and a Black woman, who did not identify their religion to me; and, including myself, two Jewish men. The people who talked with me, who comforted and were comforted, either were among the group the shooter targeted, or knew too well how being targeted feels, and, it seems, drew on their suffering to empathize with mine. In that sense, we strove to live out the commandment repeated in various phrasings most often in the Torah: “Love the stranger … for you know the soul of the stranger … for strangers you were in the land of Egypt” (Deuteronomy 10:19;Exodus 23:9; my translations). More than one darkness haunted that day. More than one light shined from it.

***

The story includes one final element: why I was traveling from Detroit to New York City. I live in New York City, and I had been in Ann Arbor, Michigan for a cousin’s wedding. It felt in one sense surreal to celebrate in this time. How can one celebrate amid grief; how can one dance in darkness? Yet it felt in another sense profoundly replenishing, and utterly necessary, to celebrate in this time, to endure darkness and dance. We ensured — despite eleven murders by a man who hates Jews, and many others — that life would still flourish, that our family would still congregate, that we would still celebrate my cousin and her now-husband. In that sense, too, I felt my family was puncturing darkness with light.

My cousin’s brother, a cantor, officiated the wedding. Just before the groom broke the glass, my cousin the cantor mentioned the Tree of Life massacre. He spoke about the undying brokenness of this world, and the persistent need to heal it.

After the ceremony, as I talked with an older couple, both white Christians, the wife of the couple said that my cousin’s mention of the massacre made her feel relieved. She had warned her husband not to mention it, thinking it would be an elephant in the room.

As she spoke, I realized that acknowledging darkness can begin the creation of light. I feel that Judaism’s ability to acknowledge darkness is one of its great strengths — thus the Passover Seder, with its green vegetables of renewal dipped in salt water of tears, with its recounting of slavery mixed with songs of praising life and God; thus Shabbat, with its blessing over the wine that joyfully celebrates Creation, then swerves to the phrase, “a remembrance of the going out of Egypt,” then back to gratitude for a day of rest given by God with love.

When we acknowledge darkness, we free ourselves from the fear of what cannot be said, a fear that blackens darkness with further shadow. When we acknowledge darkness, we clutch our candles tighter, and feel in that tightness uncanny fond gratitude. When we acknowledge darkness, we feel the urgent impetus to spark more light. We marvel at the stubborn, gracious fact that light survives.

***

The Tree of Life Congregation takes its name both from the Eden story and from a pair of verses from the Book of Proverbs, in their original context describing wisdom, and sung in synagogue to describe the Torah following the public reading from it: “Her ways are ways of pleasantness / and all her paths are peace. / A tree of life is she to those who hold strong to her / and her upholders are happy” (Proverbs 3:17-18, my translation).

We can respond to this darkness by, amid it, creating light. We can respond by showing one another, in the names and the memories of the victims, precisely these values: pleasantness and peace, life and happiness, “kindness and truth” (3:3), and the ultimate, “Love your fellow as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18; my translation).

If it is possible in the airport, it is possible anywhere.

Noah Lawrence is a legal scholar and a student at New York City’s Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT) Rabbinical School; its mission is to train Orthodox rabbis who are “open, non-judgmental, knowledgeable, empathetic,” and committed to “the larger Jewish community and the world.” Previously, he worked in law and politics, including for Senator Richard Blumenthal, at the Israeli Supreme Court, and at the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague.