After all, the Shushan shenanigans feature a remarkably empowering female role model. It is hard to find a more revered example of heroism, or shall we say heroism, than Esther, the queen who valiantly saves her fellow Jews. And a decent argument can be made that Esther’s predecessor Vashti, who defies her husband King Ahashverosh, is a feminist before her time.

But reframing even a story helmed by a heroine allows us to unmask stereotypes on a holiday filled with masks. Let us begin with a reading from the pretend Book of Elmer:

* * *

Many moons ago, Queen Ashley reigned supreme in the land of Persia and held court in the ancient capital of Shushan.

At one of her many ostentatious parties, Queen Ashley drunkenly commanded her husband, King Vinny, to parade his handsome body in front of all the female guests. When Vinny refused, the queen banished Vinny as a lesson to all the husbands who might be tempted to disobey their wives. Queen Ashley followed up with an admonishment to all the wives in the queendom to rule their roosts.

After ridding herself of Vinny, Queen Ashley held a beauty pageant to find a new hubby. Virginal young men came from all around to compete for her favor, each flexing their muscles to show off their sculpted physiques. When one very attractive boy, Elmer, was brought to the palace, the queen liked what she saw and picked him from among the assembled hunks.

After getting hitched, Queen Ashley and King Elmer lived happily ever after—nope, scratch that ending. In truth, the story was just heating up.

Unbeknownst to the queen, Elmer was Jewish. On the advice of his wise cousin and foster mom Marilyn, Elmer kept his religious identity a secret.

The queen’s prime minister was an anti-Semitic witch, Hazel. When Hazel strutted through Shushan, she made all the townspeople bow down to her. But Marilyn, a Jew, refused. Infuriated, Hazel cooked up a wicked scheme to wipe out Marilyn and all the Jews throughout the provinces.

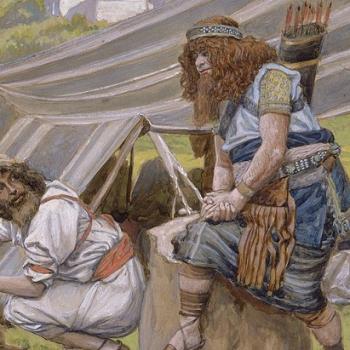

Learning of Hazel’s foul plan, Marilyn appealed to King Elmer to intercede with the queen. Though King Elmer was initially afraid to approach Queen Ashley, he agreed to do his best to save his people from annihilation.

Adorning himself in royal garments and plucking up great courage, King Elmer invited Queen Ashley along with Hazel to a feast. There he bravely revealed that he was Jewish and beseeched the queen to spare the Jews from Hazel’s vile plot.

Queen Ashley granted the king’s request and overrode Hazel’s murderous decree. Recalling that Marilyn had once foiled an assassination attempt on the throne, Queen Ashley promoted Marilyn to prime minister and sent Hazel to the very gallows that Hazel had constructed for Marilyn.

The merry holiday of Purim commemorates this miraculous survival of the Jews in the face of an existential threat.

* * *

While the leitmotif of Purim is anti-Semitism, gender is surely the lite motif.

Much of this altered version of the Purim scroll is not jarring. We do not bat an eye when a hero, King Elmer, subs in for a shero, Queen Esther. Nor do we have much trouble imagining a queen running the show or a villainess mistressminding an evil plot.

What does give some of us pause, though, are the scenes that run counter to our prevailing cultural associations.

In the #MeToo era, it is far more commonplace to hear that Vashti rather than Vinny is the victim of sexual harassment and thwarted opportunities. Likewise, when a contest hinges on appearances, we are more accustomed to a beauty queen like Esther than a beauty king like Elmer. The Bachelorette is a spinoff of The Bachelor, not the reverse.

So too, the queen’s dictate for all wives to man up as heads of their households screams fictional, while the converse sounds only too familiar. When King Elmer at first fears speaking to Queen Ashley, he is clearly not the one in the family who wears the pants—what a revealing idiom—even though both wear crowns.

But not so fast. Perhaps the presence of a strong leading lady in the Biblical account primes this modern makeover to sit more easily with us. Possibly Shebrews like Marilyn feel just about as natural as Hebrews like Mordecai. Maybe just maybe, to the extent that we can look past gendered typecasts, we can reconfigure our own stories in our own time.

As you chew over which casting changes work seamlessly and which cause you to do a double take, have a bite of hamentaschen. Only this year, let’s call it hazeltaschen.

Jan Zauzmer, a past president of a large URJ congregation, has reimagined Passover, Hanukkah, and now Purim.