I’ve written here about the urban gardens movement that I see now almost everywhere I go these days. (Our friends at MSA are tracking this movement, too). Most of the time, these gardens are being planted by the new-comers to our nation’s abandoned inner-cities. That’s certainly been the case here in Walltown. But I was delighted to visit the Hoover Garden in Little Rock, AR, earlier this year and to learn that it was started from within one of the neighborhood’s landmark churches. One of this movement’s writer/practitioners, Ragan Sutterfield, helped a group dig begs for a pizza garden while I was there. Now that the crop is in, he returned to write this report for The Everyday Awakening.

By Ragan Sutterfield

Riding my bike the few blocks to the Hoover Garden I start to think about space—how it’s used and who controls it. The neighborhood I’m riding through, called the 12th Street Corridor, is a space that’s been defined by passing through. The other neighborhoods nearby are called things like Hillcrest or Stifft Station or the Quapaw Quarter. These are the names of stable places, but the 12th Street Corridor—that’s the name for a place most people just drive right through and never stop. The result is a neighborhood that is dying; abandoned houses on every block, empty lots marking the places that have been burned down or bulldozed, never to be rebuilt again. It’s the kind of place you go through or leave, not the kind of place you stay.

But right on 12th Street, beside a house that was once abandoned and on a lot that once looked like the weed and trash filled vacant spaces dotting the neighborhood, new roots are going down and a garden is growing.

I arrive at the garden, struck by how close it is to where I live, and yet so different. There are big oaks framing the quarter acre, and two large stone lined perennial beds. On the other side there is a chain linked fence with morning glories climbing along it. The fence surrounds several large raised bed garden plots, a few of which are in the process of being torn down to accommodate a new irrigation system. Its late summer and the garden is getting ready to transition to Fall crops.

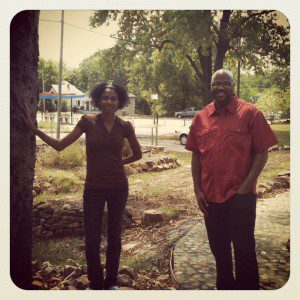

Malik Saafir pulls into the driveway, just in from teaching an ethics class at a local college. Malik is young, in his 30s, and just moved into the Senior Pastor role at Theresa Hoover UMC which sponsors the Hoover Garden a block away from the church. Malik is light hearted, yet professorial-ready to talk Tupac or Derrida in equal measure. He grew up in low income neighborhoods in Little Rock much like the 12th street corridor and found his way to education in big prestigious institutions like Vanderbilt, where he completed his M.Div. But rather than using that cache to land a job in a big city, Malik came back to Little Rock motivated by a desire to teach people in the community a holistic vision of life that emphasizes environmental justice, of which the garden is a critical part. Looking over the beds and talking about his vision for an environmental justice center out of the church, Malik says “the way this planet is headed, and the way lower income communities are going to be adversely affected by the limitation of resources, there is no doubt in my mind that we need to learn what to do to achieve the localization of food, the establishment of food sovereignty, and what we need to do to develop communal wealth.”

Saafir sees this garden, which was established through the work of his friend Gerald Cound, as a place to train people to become more self-reliant and at the same time community-reliant. The house which sits on the same property as the garden serves as work space for several local non-profit organizations and just across the street from the property is a community center. Saafir says that “With the links to both a spiritual place and a community center the garden is a kind of bridge to draw people through their faith into the green movement.”

As we talk, Adrea Coley the garden manager pulls in. She’s just finished her master’s degree in writing at a local university and created a community gardening manual utilizing her experience at Hoover to guide others into operating a community garden. Coley even designed a story board for a Sim City like garden video game to teach kids about gardening, using an apocalyptic future when oil will no longer be available, a fact that reflects the many surprises of her quiet demeanor.

Adrea jumps into the conversation with self-deprecating humor. She shares about how one of the motivations for her to join the work of the garden is independence. “Knowing how to grow your own food makes you less dependent on big systems to grow your own food and also provides a way to make income with your own hands,” she says. For both Coley and Saafir, an important aspect of getting people of color involved in gardening is the opportunity for self-reliance. As Saafir says, “For people who have a cultural history of farming for other people on other people’s land it is important to create a way for people to enjoy the fruits of their labor.”

In the August heat those fruits are hard to come by, but slowly, people are being drawn into the garden and learning the necessary skills for a more abundant future. Two kids jump a fence and run down to Adrea. “These are my watch dogs,” she says smiling at the boys, “they watch out for the garden and make sure no one messes with it.” The boys grin back and run around the plots. We look over the rows and talk about irrigation, the possibility of adding some rabbits, and dream dreams that we all hope will take root and claim this little patch for a new kind of kingdom.

Ragan Sutterfield is a writer and agrarian in Little Rock, Arkansas. He is author of Farming as a Spiritual Discipline and writes Soul W.O.D., a blog of daily spiritual exercises.