“The Holy Spirit is no skeptic…. a man must delight in assertions or he will be no Christian.” — Martin Luther to Erasmus

Post by Nathan Rinne

Recently, in an interesting First Thoughts piece on the current debates about Karl Barth, the name of Immanuel Kant was invoked.

The author of the article, Philip Cary, stated that for Kant: “The intelligibility of the world lies not in the substance of things [i.e. “their formal being or essence”] but in the a priori categories imposed on it by our active, conceptualizing minds.” As Cary states, Kant came up with this idea because “we have no intellectual faculty for knowing the essence of things in themselves.” (to have Kant’s view explained in some detail in layman’s terms, give this fine podcast a listen)*

On one level, I submit that Immanuel Kant’s fight was real: for him, he was fighting to preserve the reality of free will for humans vs what he saw as the reductionism and determinism of the natural sciences (a focus of mine to), whose clout was increasing due to piling up success after unending experimental (and practical!) success. And yet, whether he intended to do so or not, Kant created a system of thought where there was no need for Divine revelation – where Divine revelation was something that could just be “tacked on”, but didn’t really fit into the overall picture. In this sense, he was not all that different than any other philosopher who has come to capture the hearts and minds of elite men and women (I also find it fascinating that he was evidently sufficiently vague [British: “shifty”] that scholars today actually argue over whether he was atheistic, theistic, panentheistic, or pantheistic, but I’ll leave that important observation alone for now). And to say this, of course, is not to insist that he may not have had some good ideas, (“denying knowledge to make room for faith”, and saying that the “world of appearances”, or “phenomena”, counted as knowledge were not these…) gotten some things right, etc. – only that his focus was not where it should have been (see Acts 17 to get some focus).

Cary’s piece put me in mind of something I had read recently in liberal theologian Gary Dorrein’s recent and ambitious revisionist work Kantian Reason and Hegelian Spirit: the Idealistic Logic of Modern Theology.

Dorrein begins by speaking about classical political liberalism (all bold are mine):

Historically and theoretically, the cornerstone of liberalism is the assertion of the supreme value and universal rights of the individual. The liberal tradition of Benedict de Spinoza, John Locke, Charles Louis de Sceondat Motesquieu, Immanuel Kant and Thomas Jefferson taught that the universal goal of human beings is to realize their freedom and that state power is justified only to the extent that it enables and protects individual liberty….

…and then goes on to say about liberal theology:

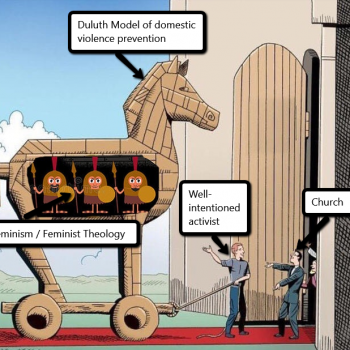

The founding of modern theology is an aspect of this story. Liberal theology, in my definition, was and is a three-layered phenomenon: Firstly it is the idea that all claims to truth, in theology and other disciplines, must be made on the basis of reason and experience, not by appeal to external authority. From a liberal standpoint, Christian scripture or ecclesiastical doctrine may still be authoritative for theology and faith, but its authority operates within Christian experience, not as an outside word that establishes or compels truth claims about particular matters of fact.

Secondly, liberal theology argues for the viability and necessity of an alternative to orthodox over-belief and secular disbelief. In Germany, the liberal movement called itself “mediating theology” because it took so seriously the challenge of a rising culture of aggressive deism and atheism. Liberal religious thinkers, unavoidably, had to battle with conservatives for the right to liberalize Christian doctrine. But usually they worried more about the critical challenges to belief from outsiders. The agenda of modern theology was to develop a credible form of Christianity before the “cultured despisers of religion” routed Christian faith from intellectual and cultural respectability. This agenda was expressed in the title of the founding work of modern theology, Schleiermacher’s Uber die Religion: Reden an die Gebildeten unter ihren Verachtern (On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers). Here, Britain was ahead of the curve, as there was an ample tradition of aggressive British deism and skepticism by the time that Schleiermacher wrote. British critics ransacked the Bible for unbelievable things: in Germany, a deceased anonymous deist (Hermann Samuel Reimarus) caused a stir in the mid-1770s by portraying Jesus as a misguided political messiah lacking any idea of being divine; Schleiermacher, surrounded by cultured scoffers in Berlin, contended that true religion and the divinity of Jesus were fully credible on modern terms.

The third layer consists of specific things that go with overthrowing the principle of external authority and adopting a mediating perspective between authority religion and disbelief. The liberal tradition reconceptualizes the meaning of Christianity in the light of modern knowledge and values. It is reformist in spirit and substance, not revolutionary. It is open to the verdicts of modern intellectual inquiry, especially historical criticism and the natural sciences. It conceives Christianity as an ethical way of life, it advocates moral concepts of atonement and reconciliation, and it is committed to making progressive religion credible and socially relevant.

This definition is calibrated to describe the entire tradition of liberal theology from Kant and Schleiermacher to the present day….. The key to the ascendency of liberal theology in the nineteenth century is that it outgrew its origins as an ideology of freethinking criticism to become a theology in, and at home with, the Christian church. (pp. 4-5, 6).

Of course, this is where traditional orthodox theologians must disagree with Dorrien, however right his diagnosis to this point. This goes back to the main argument of J. Gresham Machen, who asserted – rightly, I think – that liberal Christianity and biblical Christianity were two different religions. Theologically freethinking criticism and the Household of God don’t really go together (I think the late confessional Lutheran theologian Kurt Marquart had a deep grasp of the issues, and made this argument quite effectively – see here).

The difference, of course, is that the biblical theologian stands with the earliest theologians of the Christian church: he states that the very Word of God, as put forth in the written Scriptures, is true, and that it speaks of purposeful, discernible realities that exist outside of us. This makes it relevant and incapable of becoming irrelevant – whatever the “Spirit of the Age” may think – and all else follows from this simple point.

And not only this, but Christians are those who make assertions not only about what is true about God and man, but the rest of His creation and the personal intentions discerned within. This means, among other things, that ancient metaphysical ideas of “substance”, for example, align more closely with the teachings of the Bible*** than does the Kantian alternative, still in vogue today in a myriad of different forms (underlying a whole spectrum of “mediating theologies”). To say this does not mean that man can, with or without the Scriptures, accurately discern and assert the intrinsic purposes of all the things in the cosmos. It does mean however, that even without taking the Scriptures to be God’s word, man is able to accurately discern and assert some of the intrinsic purposes of some of the things within it (which should not be surprising, since the latest and greatest theories of smarter skeptics are moving in this direction anyways, as I pointed out in the last post on my personal blog here).

After all, as the Psalms say repeatedly: “the fool says in his heart: ‘there is no God'”. And as Paul writes “[the] divine nature… [has] been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.” Even if one thinks that Paul is only talking about conclusions made from the deductions of our sensory experience or that he only says this by virtue of our having innate knowledge due to our “intellectual apparatus” (in Kantian terms, “synthetic apriori” stuff, the “metaphysic of experience”), Kant (we can have “strong convictions” about but not knowledge of free will, morals, rational agency, good and evil, the soul, God, etc.) gets decidedly left behind by these revealed assertions of God through His apostle – and some classical philosophers, on the other hand,**** perhaps get our grudging respect…

FIN

Notes

* More from that quote:

“It is not the mark of a Christian mind to take no delight in assertions. On the contrary, a man must delight in assertions or he will be no Christian.

And by assertion– in order that we may not be misled by words– I mean a constant adhering, affirming, confessing, maintaining, and an invincible persevering. Nor, I think, does the word mean anything else either as used by the Latins or by us in our time.

I am speaking, moreover, about the assertion of those things which have been divinely transmitted to us in the sacred writings… Nothing is better known or more common among Christians than assertion. Take away assertions and you take away Christianity.”

–Martin Luther, The Bondage of the Will, in Luther and Erasmus: Free Will and Salvation, Eds. E. Gordon Rupp and Philip Watson (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969), 105-106.

** Cary goes on: “*But we can make scientific sense of the world because its conceptual structure and intelligibility come from us, from the activity of our minds as we conceptualize the data of our sense experience”

*** While most all of modern academia shuns notions of essence/substance, a notable exception is this quote from Hans Ulrich Bumbrecht, professor of Romance languages at Stanford University, from his 2004 book “Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey”:

What I want to say….is that there is probably no way to end the exclusive dominance of interpretation, to abandon hermeneutics… in the humanities without using concepts that potential intellectual opponents may polemically characterize as “substantialist,” that is concepts such as “substance” itself, “presence,” and perhaps even “reality” and “Being”. To use such concepts, however, has long been a symptom of despicably bad intellectual taste in the humanities; indeed, to believe in the possibility of referring to the world other than by meaning has become anonymous with the utmost degree of philosophical naivete – and until recently, few humanists have been courageous enough to deliberately draw such potentially devastating and embarrassing criticism upon themselves. We all know only too well that saying whatever it takes to confute the charge of being “substantialist” is the humanities on autopilot (bold mine, quoted in Armin Wenz, Biblical Hermeneutics in a Postmodern World: Sacramental Hermeneutics versus Spiritualistic Constructivism, LOGIA, 2013)

As I noted in the past: “In other words, almost no one today in the academic world is a “substantialist”, or we might say “essentialist” – to suggest that there are things in the cosmos that have firm categories of being, or essence, or substance, is anathema, for the universe is in flux. To suggest that some of these things have an objective meaning or purpose we can discern takes even greater hutzpa. Now, it is likely that some in the fields of the humanities see what has become their arch-nemesis, science, as being “essentialist”, however one notes the primacy (and difficulty) of interpretation in the modern sciences as well: to speak of essences is to speak of atomic particles, and not things we regularly see and experience in the cosmos, like males and females, and marriages and children, for example. More importantly, the particles and assemblies of particles might “mean something” in a purely material sense – showing themselves to have a certain order and predictability – but a greater purpose in those things that contain them can only be a total mystery (I talked about the despair this creates here).”

**** Very interesting and helpful listening on Aristotle’s notion of the four causes: http://www.historyofphilosophy.net/aristotle-four-causes