+++

Post by Nathan Rinne

+++

Hi.

My name is Nathan and I’m out to kill Jack Kevorkian’s World, aka the Culture of Death.

I spent a good amount of time on this post because there are very weighty things at stake. If you pay attention to the right places, you’ll see that the themes are now persistent, suffocatingly so.

Sometimes, it seems to me like one side came to play and the other didn’t.

And really, it’s a bit personal for me.

In fact, I wrote this longer post, supplemented by detailed footnotes at the end, largely to inform and inspire myself. And to give me a place to refer to when the gaslighting gets really bad.

I will admit that at this point my mind is pretty much made up. In sum, any argument about morals and ethics can’t not come from the conviction that killing innocent life is always wrong.

And so frankly, at this point, I mostly identify with those who are inclined to mock the Culture of Death.

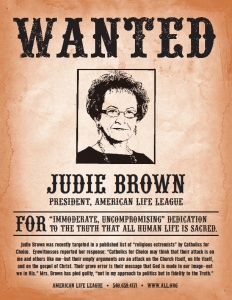

— Canadian journalist Andrew Coyne (note: all such pictures, unless otherwise noted, found via CCS)

All that said, I hope that you might [nevertheless?] give me your ear about what is quick becoming the duty to die by dehydration — and why you should fight it.

Still, even before we dive into that, it needs to be made clear in no uncertain terms that culture of death increasingly gains influence and surrounds us.

Sometimes, it seems like nothing can stop it:

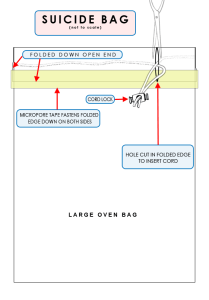

- Up to 25% of assisted suicides fail, leading Derek Humphry to recommend death by bag (suffocation) in this instance and other medical professionals to recommend doctors be trained to kill more effectively when typical means fail. (Smith, Culture of Death, 135 [all numbered Smith references are to this book])

- Hollywood produces a film called You Don’t Know Jack, starring Al Pacino as the late “Dr. Death” Jack Kevorkian, and it either does not know Jack itself or hides the true motivations for his work, clearly revealed in his own writings.

- Parents in Washington state who get a lawyer to fight the hospital that discontinues dialysis on their very premature baby are reported to child protective services, and accused of “physical abuse” and “physical neglect”. (Smith, 141)

- “Futile care” isn’t refused because its “useless”, but because it does or may work (extending life) (Smith, 175)

- “Medical discrimination based on age or state of health and disability is promoted in the name of an alleged need for health care rationing in our most notable professional journals.” (Smith, 253)

- The main thing driving the futile care theory (FCT) in the world of bioethics is utilitarian notions of “distributive justice” (vs. the “Hippocratic ethic”, Smith, 170) and the major rationale for this attempted policy change is cost-cutting and control. (Smith, 165-166)

Dutch “doctor,” Bert Keizer, depicts “the love of frail and dying people” as “pointless, useless, ugly” and “grotesque” and those who want to care for them as “selfish, greedy, stupid, and unloving”. (Smith, 136, 137)

“Sustainability [means t]he aim is to overcome the present assumption that health care should be tailored to individual needs… a sustainable medicine can do no other than accept this unpleasant reality…” (Daniel Callahan, quoted in Smith, 170)

+++

Do we yawn? Or do we say “we must fight this! As for me and my house…”?

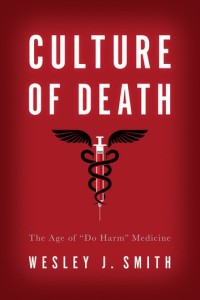

I pray the latter. For as Wesley J. Smith, the author of the exceedingly sad but honest 2016 book Culture of Death, puts it,“The lure of death is becoming like a black hole from which little light escapes.”

In such an environment, it only makes sense that the duty to die by dehydration increases daily for some who find themselves in particular circumstances.

In America, no one can legally do this against your will yet – though, strengthened by the short-sighted and ultimately selfish decisions of those who do willingly choose forms of assisted suicide – that kind of tyranny is undoubtedly coming.

If you don’t believe this, spend just a little bit of time reading or listening to men like Wesley J. Smith or speaking with groups such as the Coalition of Concerned Medical Professionals, Western Service Worker Associations, or basically any group serving the disabled.

So — maybe you’ve had an experience where this happened in your family or with a friend you know?: someone you loved was basically dehydrated to death, with or without their consent?

Perhaps you had been told by them…

- I don’t want any machines at all to keep me alive.

- You just need to let me go.

- It’s my “right” to choose this. Its my “right” to die.

- We all have to die sometime. And it’s really all about the soul, not the body.

Or their doctors…

- We don’t even let animals die such a horrible death! And you want to, for the sake of your arbitrary rules?

- She’s not responsive. What you are seeing there is just a reflex at this point.

- Any second opinions you get at this point will most likely tell you what I’ve told you…

- Maybe what you want to do—prolong life—is standing in the way of God…

- Don’t think for a minute this is murder. This is a “good death” (euthanasia)[i] “Mercy killing”!

Really now — don’t you know you do not have the right to demand care doctors do not believe should be rendered? As one put it: “Doctors have to maintain their professional integrity…they are not to be likened to plumbers…” (Smith, 163)

So then, maybe it is alright to dehydrate a person to death sometimes? Maybe the real question is not whether some lives are beyond saving but whether they are worth saving?

No. Never. Don’t let yourself be lied to by those who ignore God or even have no regard for Him. Food and water cannot be considered medical treatment because all persons, regardless of who they might be or what their circumstances, always need these things.

The church of the Lord Jesus Christ has always been clear on this. And, any of those practicing medicine have quite a historical legacy as well, even if now, increasingly “wise,” they spit in its face.

And believe it or not—you’d never know it from the way doctors speak today!—American culture was also basically clear on this too, up until the 1980s that is,[ii] when the Reagan administration’s “Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research” suggested the contrary…

First, artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) became a “medical treatment”. And now, people are regularly dehydrated in all fifty states of the union. Not only this, but bioethicists increasingly argue that spoon-feeding should be removed from dementia patients who willingly eat but who before their dementia said they would not want life-sustaining treatment (Smith, Culture of Death, 2016, 62, 65, 85)

One might think we would just know that starving and dehydrating people to death is wrong!

So, what happened? Well, no great discovery was made which ushered in this New Age. On the contrary, human beings have just become that much more individualistic, blind, callous, heartless, and selfish.

The ways the most sophisticated among us deceive ourselves increases and our sin piles up, especially in a Westernized Enlightenment context eager to snuff out remaining Christian light.

So, who will call out the deception? Who will resist and demand things change? Who will say “Repent!”?

Who will demand that persons created in the image of God and bought with the blood of Jesus Christ be truly honored as they should be—even if that means by not having their own wishes honored?

I have been heartened by the clear and firm words found in the LC-MS document by John Pless “Mercy at Life’s End – The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod” (p. 10-11):

Suffering is not to be confused with evil. Here Luther’s theology of the cross is helpful. Note Thesis 21 of the Heidelberg Disputation: “A theology of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theology of the cross calls the thing what it actually is.” Our vocation in serving those who suffer is to provide merciful care even when there is no cure. We are never to purposefully use death as a means to terminate suffering in the name of compassion. “The principle that governs Christian compassion, however, is not ‘minimize suffering.’ It is ‘maximize care.’ Were our goal only to minimize suffering, no doubt we could sometimes achieve it by eliminating sufferers. … Always care, never kill.” This guiding principle also is reflected in a statement produced by the Ramsey Colloquium, a group of Christian and Jewish theologians, philosophers, legal scholars and ethicists, in a 1991 document titled Always to Care, Never to Kill: A Declaration on Euthanasia. It says: “In relating to the sick, the suffering, the incompetent, the disabled, and the dying, we must learn again the wisdom that teaches us always to care, never to kill. Although it may sometimes appear to be an act of compassion, killing is never a means of caring.” (bold mine, for the very practical nitty-gritty stuff in this document, see especially pp. 12-15, looking carefully at the questions on page 15 [and see pages 20 and 21 as well for key questions]).

Amen!

+++

At the same time, sadly, Dr. Pless’ convictions are not monolithic in a church body like the LC-MS either. And some, while speaking clearly to the issues in an academic context, would no doubt find a post like this one to be counter-productive.

In truth, I must confess that it is my impression that the Christians who understand this issue and this spiraling-out-of-all-control process the best today–and/or are the most concerned and cautious about it–come from the Roman Catholic communion.[iii]

This is a communion, which, of course, also has a very strong reputation for being pro-life on the other end of life’s spectrum as well. Many of us know that it was Pope John Paul II who coined the term “the culture of death.”

As best I can tell, even those from the more liberal quarters of the Roman Catholic Church appear to be more anti-euthanasia than, for example, most all conservative Protestant Christians!

After all, they generally frame the main issue in such a way, that, on the face of it, their more conservative Roman Catholic counterparts can agree with them!

For example, the more liberal Daniel Sulmasy writes that “The Church has always taught that suicide and euthanasia are morally wrong. The Church, however, has never required that a person do everything medically possible to prolong life.”[iv]

That is true. It is possible, for example, that a person might be able to be weaned off a respirator and be able to breath on their own, but this will not always occur. Here, the Roman Catholic church, according to a long church tradition, has said that there are situations where it might make sense for individuals to decide (it should definitely be their choice, given they are able to make it) to no longer be kept alive indefinitely in such a state.[v]

At the same time, this is also where more liberal Catholics in the vein of Sulmasy might make the case that in particular situations there is “no moral difference between removing a respirator, antibiotics or artificial feeding.”[vi]

This seems like a convincing line of argument because if food and water can’t be considered medicine or treatment, but basic care, isn’t that also true about air (oxygen)?

There are in fact a number of reasons why this is not really an analogous situation.

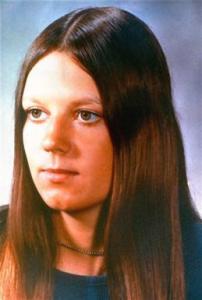

First of all, as with the Karen Ann Quinlan case in the 1970s, if you turn off a ventilator/respirator, you don’t know for a fact whether the person it is helping will not be able to continue to breathe or not. When you withhold food and water, you can be 100% assured that even the patient most determined to live will die. Here, it hard not to conclude that death is the aim, even if some are not fully conscious of this intention. As one man, writing in First Things, put it “if I decide not to treat because it seems a burden just to have the life this person has, then I am taking aim not at the burdensome treatment but at the life.”[vii]

Second, Eugene Diamond, M.D. points out, providing food and water can’t be considered a medical procedure, since it is possible that—other than something like the initial insertion of a nasogastric tube—this act can be “performed by family members in a domestic environment.”

Third, when it comes to what human beings are designed to do, there is a big difference between how we breathe and how we eat and drink. According to the more liberal Roman Catholic ethicist John Collins Harvey, there are some incidents of comas—where cells have died in the cerebral cortex—where individuals “have no voluntary motor power,” and therefore “the physiological mode of death for such a patient is dehydration…” (“Sampling of Responses to the CDF Statement on Nutrition and Hydration”).

This is simply not true. Generally speaking, human beings always need to be able to breathe by themselves in order to function in this world. We can’t and don’t breath for other persons. It is not something that others need to help them with, or, for that matter, could, for any extended length of time. On the contrary, we often do feed one another, and this is nothing extraordinary.

In its earliest days, a human child can’t feed itself for up to a year.[viii] Many who have situations like cerebral palsy consistently need assistance when it comes to eating and drinking. And my mother-in-law, increasing in age and a form of dementia, needs much help being fed these days! Is feeding in these cases something optional (or “extraordinary”[ix] as some might say?)?

“Wait,” some interject here. What if a person is having trouble swallowing though? Well, these days it is well-known that therapy can often be used to help many patients to manage this and improve (as neurologists and physical therapists work together).[x] And if that is failing there are other options.

The objections continue to come though, fast and furious. John Collins Harvey, for example, mentioned above, goes on to state that “the physiological mode death for [certain comatose] patient[s] is dehydration [because] they do not have the abilities to bring food and fluid to their mouth, nor, if such is put into the mouth, to chew and move it to the posterior part of the tongue nor to swallow it into the esophagus.”

So, hearing this, persons might just feel compelled to ask, “What about these kinds of persons who can’t swallow and need some kind of tube feeding? Isn’t that optional? Something that goes beyond our normal obligation to take care of ours and other’s bodily lives?”[xi]

The question is “Why would we assume this?” “Unconsciousness,” the National Catholic Bioethics Center states, “is not a fatal disease. No one dies from unconsciousness.”

Even if, for example, the person has suffered the extremely rare situation of severe brain damage (“hard cases make bad law,” by the way) which causes their ability to interact with other people to be in doubt (at least for some – here, one thinks of the tragic case of Terry Schiavo, and the contrasting accounts of husband vs. family members)!

And even if a person is experiencing “post-coma unresponsiveness,” sometimes disparagingly called a “persistent vegetative state”[xii] (are you aware, by the way, of how several of these “vegetables” are really conscious to some degree[xiii] and even wake up?[xiv])!

Here, in spite of what more liberal Roman Catholics state[xv], the presumption should be for food and water.

Forms of tube feeding were known even in the ancient world.[xvi] Furthermore, this is neither a technological nor financial impossibility for most any family in the Western world, much less an extended family.[xvii] With patient explanation, most all fears of tube feeding can be alleviated. And then, all in the family can pitch in and better learn what it means to love by suffering with one another.

It is one thing when a person stops eating because their body is shutting down, and death is imminent (this might be a “terminal illness” in its last stages, where one is, at that point in time, “irretrievably dying” – not just conditions which are “incurable” or “irreversible”[xviii]). Here, the appetite often diminishes and one is not desiring to cause death, but is rather merely recognizing one’s inability to hinder it.

More details in the last section. We need to see all the connections. All the implications.

+++

In case it has not been made clear yet, dehydrating persons is wrong.

I have read a great deal from persons in the medical field who have thought long and hard about this, and the only times when it might be necessary to remove feeding tubes is when:

- The organs begin to shut down and stop working and are no longer able to process or assimilate the nourishment given.

- When there are serious complications such as aspiration pneumonia or infections that are resulting from it.

- Indeed, “in some rare cases, artificial nourishment and hydration may be excessively burdensome for the patient or may cause significant physical discomfort..”[xix]

Additionally, there is all kinds of compelling evidence that being dehydrated to death is absolutely horrific (see here, here, here, here, and here).[xx] This should hardly be surprising, given how much water is in our body and that none of us were created by God with dehydration in mind. Knowing this kind of thing would probably cause most of us to say “stop,” but for others, it just means that more aggressive steps to hasten death—using some kind of “hemlock,” for example—might be necessary.

So, in sum, we don’t dehydrate or starve people and actively cause them to die, being a contributory cause of their death. And we also don’t, by the way, let people use sedation as an aid to killing (see page 2 here.) – instead of its rightful use which is to control pain.

We call that assisted suicide, or, yes, more directly, murder. Oh, and coveting a person’s organs, as many in the medical profession are now doing, doesn’t make you less guilty, but more so!

And if you still resist what is being argued here, think about this: Do we even think about the wider implications of what it is that is being done? Someone says that he would not want to live the rest of her life in bed… Should he have the right to make that choice?

Wesley J. Smith is right to tell us to fight:

- Reform hospice!

- Close the door to futile care theory!

- Hold the line in dehydration cases!

- Continue the struggle over abortion!

- Prevent “medical martyrdom”! (where doctors can’t be Christians, take the Hippocratic Oath)

- Beware the “New Eugenics”! (eschew the new “biological colonialism”)

- Remember that words matter!

- Learn from the disabled community!

- Affirm the value of life! (Smith, 253-287)

Count the cost. Take the risks.

And be active, particularly if you would be one of the ones who will have or who will likely have “power of attorney” (where you are the one charged with carrying out the patient’s will, making the tough decisions). Ask them about this kind of thing now, before it happens and even before they fill out any advanced directives.

If your loved one persists in refusing aid and your help, how will you communicate to them how serious this matter is to you? I know all of this might seem insensitive to the “rights” people feel they have and, depending on the steps that you take in order to reach them (they might say: to control us!), even manipulative, cruel, and perhaps worst of all, coercive.[xxi]

So be it. Fight.

Why not? After all, even if I am not sure what to think when I hear Julie Grimstad, contra Wesley J. Smith, say

“If the goal is to salvage healthy organs, haste is of the essence in determining brain death. Haste can lead to cutting corners and to errors… People who have been determined to be ‘brain dead’ using the most rigorous neurological criteria have awakened and recovered,”[xxii]

…I suspect she will have some important things I need to hear.

We all respect conviction.

And, when it comes to the things that we do know, we must act in truth and love. For there is not only life here on earth but in the world to come…

And do you really want to be a willing accomplice to murder?

Do you want to have to answer to God for that?

Are you really ready to make your case before Him about why you think everyone was justified in avoiding the suffering that He may have intended to use for good?

It is true that we don’t, or shouldn’t, hold God accountable when human beings willingly choose to do evil and He doesn’t stop them. We can’t know or judge His plans, after all. At the same time, we are not God. We are accountable.

Perhaps you have been involved in a situation like this, and you are sensing that you failed. Even if you were not the one charged with making the final decision, you sense that you need to repent about your unwillingness to at least warn others, and to make the truth known…

It is good to think about these matters for the sake of making things right now – what could you have done? What actions do you think you should have performed (involving certain consequences you may have even felt were necessary) in order to try to get through to them?

Know, above all, that there is forgiveness for all such sins in Jesus Christ.

+++

None of this is easy. And again, as a Christian, you should be prepared to face a situation like this, for it might well sneak up on you unexpectedly.

And this is where it helps to speak with many Hippocratic-oath-affirming doctors with different specialties can work together to find the best path forward.

And then, you and those you love can find joy and peace in patiently soldiering on with our Lord, who has called us to fight the good fight, even through suffering we would often rather avoid.

In order to win us eternal life, we know our Lord Jesus Christ suffered on our behalf, and while through this He has taken all of our sins, He has not taken all of our own suffering away.[xxiii]

Our suffering, on the contrary, is deeply meaningful, and teaches us more about His work for us and in us.

FIN

Notes

[i] On the American Family Physician’s site we read this:

“Is withdrawal or withholding of treatment equivalent to euthanasia?

No. There is a strong general consensus that withdrawal or withholding of treatment is a decision that allows the disease to progress on its natural course. It is not a decision to seek death and end life. Euthanasia actively seeks to end the patient’s life.”

Often, what we see in writings on this stuff from the medical community is a denial of the obvious. Of course they have a vested interest in not appearing to deny the Hippocratic Oath.

[ii] Robert D. Orr, M.D., who as of 2004 was the Director of Ethics for Fletcher Allen Health Care and Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Vermont College of Medicine, acknowledges the following while writing against the general obligation to tube feed: “It was recognized many years ago that respirators, dialysis machines, and other high-tech modes of treatment are optional. They could be used or not used depending on the circumstances. However, it was commonly accepted in the past that feeding tubes are generally not optional. Part of the reasoning was that feeding tubes are readily available, simple to use, not very burdensome to the patient, and not very expensive. They were “ordinary treatment” and thus morally obligatory.” (italics mine) https://www.firstthings.com/article/2004/08/ethics-lifes-ending

[iii] This was confirmed to me by a Lutheran greatly concerned about medical ethics: “Withdrawing feeding tubes seems to have won the day in the general culture…. Outside RC circles you don’t find many people today taking this position….”

[iv] The author goes on: “This tradition is very old. In the fourth century A.D., St. Basil the Great wrote in his Long Rules (Q. 55), ‘Whatever requires an undue amount of thought or trouble or involves a large expenditure of effort and causes our whole life to revolve, as it were, around solicitude for the flesh must be avoided by Christians….Therefore, whether we follow the precepts of the medical art or decline to have recourse to them…we should hold to our objective of pleasing God and see to it that the soul’s benefit is assured, fulfilling thus the Apostle’s precept: “Whether you eat or drink or whatsoever else you do, do all to the glory of God”’” (1 Corinthians 10:31). https://www.franciscanmedia.org/are-feeding-tubes-morally-obligatory/

[v] Another example shared by Father Tad Pacholczyk: “We can consider an example that highlights these burdens: an 85 year old grandfather is placed on a ventilator after suffering several serious strokes that damaged his brain-stem so that he cannot breathe on his own. The physicians treating him are convinced that the damage from his most recent stroke will continue to get worse, with the nearly certain outcome that he will die in a few hours or days. Assuming that he is unconscious, and that other matters have been taken care of (last sacraments, opportunities for loved ones to say goodbye, etc.), the family could reasonably conclude that continued ventilation would be “extraordinary” and decide to have the ventilator disconnected, even though it would mean their grandfather would be expected to die in a matter of minutes without it. Such an act of withdrawing the ventilator would not be an act of euthanasia, because he would be dying due to the underlying condition. It would be a recognition of the burdensomeness of continued ventilation and an acknowledgement that heroics are not required, especially when death is imminent. https://www.ncbcenter.org/files/6914/6946/4143/What_About_Ventilators_June_2012.pdf

[vi] One might also hear this kind of thing as relates to the issue of kidney dialysis. This situation is analogous with the one pertaining to breathing and respirators, not eating and drinking. Fuller quote from above: “In the case of Karen Ann Quindlin, who had a ventilator removed, moralist Richard McCormick SJ, stated that, from the Catholic tradition, there was no moral difference between removing a respirator, antibiotics or artificial feeding from Karen Ann Quinlan. The ventilator was switched off.” https://www.patheos.com/blogs/voxnova/2007/07/24/when-is-euthanasia-not-euthanasia/

[vii] More context for that quote:

“Under what circumstances may we rightly refuse a life-prolonging treatment without supposing that, in making this decision, we are doing the forbidden deed of choosing or aiming at death?

The answer of our medical-moral tradition has been the following: we may refuse treatments that are either useless or excessively burdensome . In doing so, we choose not death, but one among several possible lives open to us. We do not choose to die, but, rather, how to live, even if while dying, even if a shorter life than some other lives that are still available for our choosing. What we take aim at then, what we refuse, is not life but treatment that is either useless for a particular patient or excessively burdensome for that patient. Especially for patients who are irretrievably into the dying process, almost all treatments will have become useless. In refusing them, one is not choosing death but choosing life without a now useless form of treatment. But even for patients who are not near death, who might live for a considerably longer time, excessively burdensome treatments may also be refused. Here again, one takes aim at the burdensome treatment, not at life. One person may choose a life that is longer but carries with it considerable burden of treatment. Another may choose a life that is shorter but carries with it less burden of treatment. Each, however, chooses life. Neither aims at death.

It is essential to emphasize that these criteria refer to treatments, not to lives. We may rightly reject a treatment that is useless. But if I decide not to treat because I think a person’s life is useless, then I am taking aim not at the treatment but at the life. Rather than asking, “What if anything can I do that will benefit the life this patient has?” I am asking, “Is it a benefit to have such a life?” If the latter is my question, and if I decide not to treat, it should be clear that it is the life at which I take aim. Likewise, we may reject a treatment on grounds of excessive burden. But if I decide not to treat because it seems a burden just to have the life this person has, then I am taking aim not at the burdensome treatment but at the life. Hence, in deciding whether it is appropriate and permissible to withhold or withdraw treatment, whether, even if life is thereby shortened, we are aiming only at the treatment and not at the life, we have to ask ourselves whether the treatment under consideration is, for this patient, either useless or excessively burdensome.” https://www.firstthings.com/article/2004/08/ethics-lifes-ending

[viii] Clearly, if you actively dehydrate your child, no court will say you didn’t “pull the trigger.”

[ix] In Roman Catholic teaching, the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary care is quite technical: “Catholic ethicists have attempted to delineate both objective and subjective criteria by which one is able to effectively distinguish between ordinary and extraordinary means in a given situation. Objective criteria focus on the medical effectiveness of an intervention in securing a particular clinical outcome, whereas subjective criteria focus on the patient’s own lived experience of the intervention. Elio Sgreccia specifies six subjective criteria—excessive effort, cost, pain, riskiness, low probability of success, and ‘the experience of tremendous fear or strong repugnance in relation to the application of the means’—and emphasizes ‘that it is necessary for the patient to be able to make this evaluation personally.’” https://www.pdcnet.org/ncbq/content/ncbq_2013_0013_0003_0469_0482

[x] Note: “The patient should receive food and water by mouth for as long as this is possible. Once tube feeding is initiated, it is difficult, and often impossible, for the swallowing mechanism to return. If swallowing is no longer possible, then the least invasive means of providing food and water should be used, so long as it will be of physiological benefit and will prevent the suffering or death of the patient.” http://www.ncbcenter.org/index.php/download_file/force/171/311/

[xi] “Renaissance theologians worked to determine the physical or moral impossibility of a given treatment. They listed the unobtainability or the unusableness of a means, as well as the incompatibility of the patient’s clinical condition with use of that means, as causes of physical impossibility.

Determining the causes of moral impossibility was more complex. Several of the major causes identified included extreme toil (summus labor), excessive harshness of the means (media nimia dura), certain torment (quidam cruciatus), immense pain (ingens dolor), extraordinary burden (sumptus extraordinarius), great expense of the means (media pretiosa), rarity of the means (media exquisita), and, lastly, intense fear (vehemens horror).

We can therefore summarize the traditional teachings by stating that a medical means, as well as a means of preserving life, should be considered non-obligatory when, given the subject’s clinical situation, they do not offer a reasonable benefit and there are causes of moral or physical impossibility present. Stated the other way around, they are obligatory when their use is supported by a reasonable spes salutis (hope of benefit) and there are no causes of moral or physical impossibility present.” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/002436311803888186

Again, here is a more liberal Roman Catholic take on the world “extraordinary”: “Traditionally, this has been judged to be the case if the intervention is too expensive, not likely to work, is associated with great suffering or might save the patient’s life at too great a psychological, spiritual or interpersonal cost.” https://www.franciscanmedia.org/are-feeding-tubes-morally-obligatory/

[xii] On March 20, 2004, Pope John Paul II…addressed the issue of artificial hydration and nutrition in patients suffering from the neurological condition known as the “persistent vegetative state.” He said, “I feel an obligation to reaffirm vigorously that the intrinsic value and the personal dignity of every human being does not change no matter what the concrete situation of his life.” He later said that a human being “never becomes a ‘vegetable’ or an ‘animal.’

[xiii] Recent studies have confirmed that these patients are indeed conscious to some degree. When methods of communication are established, these patients can respond to simple commands. While it is always wrong to deprive others of food and water, the fact that someone is unable to give an outward sign of awareness does not necessarily mean that he or she is unable to experience pain. http://www.ncbcenter.org/index.php/download_file/force/171/311/

[xiv] “Research in 2018 by the renowned American Academy of Neurology found that about four in 10 people who are thought to be unconscious are actually aware. They estimated the misdiagnosis rate is about 40 percent for people with severe brain injuries, including those diagnosed as persistent vegetative state (PVS), and noted that the misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment and poor outcomes.

A hopeful sign, approximately one in five people with severe brain injury from trauma will recover with proper treatment – many to the point that they can live at home and care for themselves without help, according to the academy.” https://www.lifenews.com/2019/06/28/hospital-is-starving-disabled-patient-vincent-lambert-to-death-against-his-parents-wishes/

[xv] “Broadly speaking, the Catholic Church supports advance directives, provided these are executed in a way that is consistent with Church teachings. In fact, if a person, motivated by a charitable desire to relieve others of the burdens such care might impose, executes an advance directive that states that he or she would not want artificial hydration and nutrition if ever in a state of post-coma unresponsiveness, then even the most conservative of Catholic moralists would conclude that the treatment should not be given.” (italics mine) https://www.franciscanmedia.org/are-feeding-tubes-morally-obligatory/

This is most certainly not true!

[xvi] http://www.ldysinger.com/ThM_590_Intro-Bioeth/14_nutr-hydr/history_of_tube_feeding.pdf

[xvii] “Medically assisted nutrition and hydration become morally optional when they cannot reasonably be expected to prolong life or when they would be ‘excessively burdensome for the patient or [would] cause significant physical discomfort, for example resulting from complications in the use of the means employed.’”—USCCB, Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, 5th ed., n. 58. http://www.ncbcenter.org/index.php/download_file/force/171/311/

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith offered more clear guidance in the fall of 2007 on this issue: “[T]he artificial administration of water and food generally does not impose a heavy burden either on the patient or on his or her relatives. It does not involve excessive expense; it is within the capacity of an average health care system, does not of itself require hospitalization and is proportionate to accomplishing its purpose, which is to keep the patient from dying of starvation and dehydration. It is not, nor is it meant to be, a treatment that cures the patient but is rather ordinary care aimed at the preservation of life.

What may become a notable burden is when the “vegetative state” of a family member is prolonged over time. It is a burden like that of caring for a quadriplegic, someone with serious mental illness, with advanced Alzheimer’s disease and so on. Such persons need continuous assistance for months or even for years. But the principle formulated by Pius XII cannot, for obvious reasons, be interpreted as meaning that in such cases those patients, whose ordinary care imposes a real burden on their families, may licitly be left to take care of themselves and thus abandoned to die. This is not the sense in which Pius XII[, in 1957,] spoke of extraordinary means.”

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “Responses to Certain Questions Concerning Artificial Nutrition and Hydration,” Origins 37:16 (September 27, 2007), 241-245

Again, the perspective of more liberal Roman Catholics (before the fall 2007 statement):

“Thinking about using feeding tubes in a rare condition such as post-coma unresponsiveness is very different from thinking about using feeding tubes in more common diseases such as cancer, AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, Lou Gehrig’s disease or Parkinson’s disease. Tube feeding in these types of patients will often result in great burden, no net benefit and multiple complications.

In very many such cases, tube feeding will meet the criteria by which it could be considered extraordinary or morally optional. These diseases continue to progress and get worse—no matter what treatment is offered. Complications such as pneumonia are much more common when feeding tubes are used for such patients

Patients with dementia sometimes pull the tubes out and would need to be restrained in order to be fed. In fact, in these conditions it has even been difficult to show that the use of feeding tubes actually makes the patients live longer. Clearly, in many such cases, the burdens of treatment can be judged disproportionate with respect to the benefits, and the treatment could therefore be judged extraordinary or morally optional.”

https://www.franciscanmedia.org/are-feeding-tubes-morally-obligatory/

[xviii] Athritis and disabilities like paraplegia and hearing impairment due to nerve damage are this but not “terminal”.

[xix] Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, “Responses to Certain Questions Concerning Artificial Nutrition and Hydration,” Origins 37:16 (September 27, 2007), 241-245

The larger context for this quote, which was written in regards to PVS (post-vegetative state) patients but applies more broadly, is here:

“When stating that the administration of food and water is morally obligatory in principle, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith does not exclude the possibility that, in very remote places or in situations of extreme poverty, the artificial provision of food and water may be physically impossible, and then ad impossibilia nemo tenetur. However, the obligation to offer the minimal treatments that are available remains in place, as well as that of obtaining, if possible, the means necessary for an adequate support of life. Nor is the possibility excluded that, due to emerging complications, a patient may be unable to assimilate food and liquids, so that their provision becomes altogether useless. Finally, the possibility is not absolutely excluded that, in some rare cases, artificial nourishment and hydration may be excessively burdensome for the patient or may cause significant physical discomfort, for example resulting from complications in the use of the means employed.” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/002436311803888186

Father Tad Pacholczyk writes “In some instances, providing drips and nasogastric feeding tubes can interfere with the natural course of dehydration in a way that causes acute discomfort to the patient facing imminent death. Intravenous fluids also tend to increase respiratory secretions, making it more difficult for patients to catch their breath or causing them to cough. Extra fluids may result in a need to suction the patient’s lungs. Providing IV hydration can also cause a flare up of fluid accumulation in the abdomen and expand the edema layer around tumors, aggravating symptoms, particularly pain. The use of IV drips and feeding tubes will always have to be evaluated in terms of the totality of the patient’s condition, taking into account any undesirable effects, and the likelihood of benefit.” https://www.ncbcenter.org/files/8014/7025/5378/MSOB_018_Are_Feeding_Tubes_Required.pdf

As regards patients with advanced forms of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of advanced dementia, Punzo gives a summary of a recent debate in the National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly (2013): “Howland directly critiques Gummere for focusing his arguments on the nutritive benefits of ANH [artificial nutrition and hydration] and eliding the topic of hydration. Howland writes, “From a Catholic perspective, everyone is entitled to hydration, regardless of whether or not they are capable of experiencing thirst,” and concludes the penultimate section of his paper by asserting that “failure to provide hydration to a patient who is unable to eat or drink is euthanasia by omission.” Despite the apparent universality of these principled statements, Howland does allow that clinical realities need to be considered. Specifically, Howland concedes that, if insertion of the PEG tube does not lead to weight stability or gain, if a confused patients pulls the tube out, or if the patient is dying and unable to benefit from food and liquids, then “PEG tube feeding is not required.” https://www.pdcnet.org/ncbq/content/ncbq_2013_0013_0003_0469_0482

Michael Panicola offers his commentary on the context of the September 2007 statement from the Congregarion of the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), and how overly constricting, in his view, the statement is: “…in its accompanying commentary, the CDF indicates exceptions to this general rule may apply, namely: 1) where, “due to emerging complications, a patient may be unable to assimilate food and liquids, so that their provision becomes altogether useless”; or 2) where, “in some rare cases, artificial nourishment and hydration may be excessively burdensome for the patient or may cause significant physical discomfort” (emphasis added). Given that the CDF’s statement applies only to patients in a vegetative state, which is a relatively rare condition, the net effect on patient care within Catholic settings will be minimal.

However, situations will arise on occasion as to whether artificial nutrition and hydration should be continued for patients suffering from this condition. In some, perhaps many, of these situations, I believe the CDF’s statement will pose problems for Catholic facilities. The reason I say this is because patients in a vegetative state rarely meet the exceptional criteria that the CDF outlines for discontinuing artificial nutrition and hydration. Though such patients suffer from a severe brain injury, unlike other patient populations, they do not often fail to assimilate the artificial nourishment and hydration. Thus, exception one is out. The CDF does also allow for burdens to be a tilting factor in whether or not to continue artificial nutrition and hydration. But, it’s physical burdens to the patient caused by the means, not burdens understood in the traditional sense, which could include familial, communal, and social burdens as well. Most of the evidence to date suggests that patients in a vegetative state do not experience physical burdens in the proper sense. How can this exceptional circumstance ever be met then? In reality, it most often cannot, and the CDF states as much by including in its commentary the phrase “in some rare cases” prior to allowing for the burden exception. Thus, exception two is out as well. The problem for Catholic facilities is that most people do not want to receive artificial nutrition and hydration if they are permanently unconsciousness, and many who complete advance directives specify this in writing and/or tell their surrogate. They hold this view not because they think the artificial means will fail to provide nourishment and hydration or be too burdensome but because they see no benefit to using such a means if their overall condition cannot be improved. This is precisely what the CDF has eliminated by restricting the notion of benefit to prolonging life and by declaring that nutrition and hydration cannot be discontinued solely because the patient will never regain consciousness.” https://www.chausa.org/docs/default-source/general-files/8eaa4d6ff9534d95bfdf3f20ba384f1e1-pdf.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[xx] Orr disagrees, and presumably knows of evidence I am unaware of (but would appreciate hearing more about): “’But that is no comfort! Being dehydrated and thirsty is miserable.’ Yes and no. Being thirsty is miserable, but becoming dehydrated need not be. The only place in the body where thirst is perceived is the mouth. There is good empirical evidence that as long as a person’s mouth is kept moist, that person is not uncomfortable, even if it is clear that his or her body is becoming progressively dehydrated.” https://www.firstthings.com/article/2004/08/ethics-lifes-ending

[xxi] -If this has involved another relative, will you tell those making the decision for death that they will not be speaking to your children about what happened?

-Will you tell them that you will be making less of an effort to spend time with them in the near future? That you will be withdrawing from activities and events to some degree?

-Will you tell them that, unless there is a demonstrable change of heart, you will not fail to remind their remaining family and friends that what they did was wrong?

-Will you tell them that you do not want any inheritance they have for you?

[xxii] We are told to “…consider these facts:

- A person can be pronounced “brain dead” while he or she has a normal pulse, blood pressure, color and temperature. All signs of life.

- “Brain dead” people digest food.

- “Brain dead” children grow.

- “Brain dead” pregnant women have gestated and delivered healthy babies and produced milk.

- “Brain dead” patients’ wounds heal.

- During the excision of organs, the donor is sometimes given paralyzing drugs to control muscle spasms; the heart rate increases, and blood pressure shoots up. Dead people don’t move or react to pain in these ways.

The legal definition of brain death is “the irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem.” Yet “brain dead” patients display signs that their brains retain many essential functions. [2]

If a person who has been determined to be brain dead is truly dead, then our senses are deceiving us.” https://www.lifesitenews.com/opinion/re-examining-brain-death-doctors-may-be-harvesting-organs-before-donors-are-dead

Here, the Jahi McMath case comes to mind, covered by Smith. Wikipedia states: “After viewing over four dozen independent videos of McMath, Dr. Alan Shewmon, a UCLA pediatric neurologist, declared her technically alive in a June 29, 2017, court filing, stating that the girl follows movement commands and exhibits other proof of life. Children’s Hospital Oakland maintained that the original diagnosis of brain death was correct and that the videos do not meet the diagnostic criteria for brain death.”

Dr. Paul A. Byrne specifically argues that brain death is not death because things like ventilator-facilitated respiration keeps these folks alive: “after true death chest compressions or a ventilator can only move air…” To push back on this line of thinking, Wesley Smith note that the condition of “brain death” is only made possible because of the existence of medical technology like ventilators. Perhaps, in order to stave off concerns such as these, “brain death” should not be officially declared until the bodies of artificially-respirated patients actually begin to deteriorate, and no family should ever be forced to take their loved one off a respirator? (today, they almost certainly will be). This might mean less donated organs—which many of us would undoubtedly be grateful for if we were in need of them—but would also put many minds and consciences at ease.

For Wesley Smith’s part, he has some confidence in the findings of “the American Academy of Neurology,” who in 2010 stated “there have been ‘no published reports of recovery of neurologic function [in adults] after a diagnosis of brain death.’” (I note “in adults” is there because, I believe, their bodies no longer naturally grow, but reach a point where they may only be maintained.) “None,” Smith emphasizes (see Smith, 200-205 ; on page 205-206 he looks to refute some of Byrne’s arguments, noting that he, for example, confuses “ventilation” [more a physical process related to the diaphragm] and “respiration” [more a physiological and neurological process]). Wesley Smith says the most compelling argument he heard is the following: “Imagine a person with their head cut off who is somehow kept from losing blood and whose circulatory system is intact. That is the functional equivalent of a true brain death. We can keep the body going for a time through medical technology, but would anyone really consider a headless but functioning body a living person?” (Smith, 207).

[xxiii] “This does not mean that life should be exhausted or prolonged with pointless suffering. There are significant and evident differences, however, between this, which is therapeutic stubbornness, and the withholding of assisted nutrition and hydration.” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/002436311803888186