+++

Seeking Refuge from the Law’s Inherent Goodness in the “Hidden God”? (part 5)

One might think that because of the nature of God’s law, given in Eden and still inscribed on human hearts today, Christ and the Holy Spirit should not ultimately be set against the law in any way.

As we saw in our last post however, in the Radical Lutheran account the Holy Spirit is said to be the “opposite of the law.” In his article “Luther’s Antinomian Disputations and lex aeterna” (see my response to this article in the latest Concordia Theological Quarterly here) we see that Radical Lutheran theologian Nicholas Hopman also asserts that:

- “[T]he content of the commandment/law is always a weapon attacking human sin” (159).

- “[T]he fulfillment of the law actually empties the law of all its content, namely, its threatening teeth” (160, italics mine)

- “Where there is no accusation, there is no law” (164)

- “[T]he law and delight in the law are two mutually exclusive realities” (167)

- “The Christian, in faith alone, is beyond the law” (160)

- The Christian is successful vs. sin because the Christian and Holy Spirit are not law (171)

- “[The] law is present only where Christ is absent” (164)

In sum, in the Radical Lutheran account, the law appears to be fully identified with “the hidden God” — God as human beings see him though their sin-infested reason. Again, they desire to stand before God with their good works, their “ladder theology” and/or “law story” (see part 2). The revealed God, however, has nothing to do with law, and comes in the form of Jesus Christ. He, actually, is the end of the law.

So — while Luther warned about flirting with God hidden in wrath, some modern theologians would prefer to make it a staple in how we do theology, especially when it comes to the law.

Jack Kilcrease explains “the self-evident threat posed by the hidden God to humanity” the Radical Lutheran sees:

“Relying on several remarks Luther made in his Antinomian Disputations, [Gerhard] Forde identifies the hidden God’s threatening activity with the law. Forde writes in The Law-Gospel Debate that the law must be broadly understood as “a general term for the manner in which the will of God impinges on Man…” (278).

Again, as noted in part 3, man’s response to God’s law, the nature of which is said to be our sense of accusation, is “Hell if I am going to be God’s slave.” As such, they “flee from what they perceive as the unreasonable expectations and control (oppression, coercion… punishment!) of the True God.”

Pauson and Hopman agree. And so, whatever their own intentions may be, they in any case show how Radical Lutherans can conveniently bracket God’s good law in the category of the “hidden God”…

“The resurrection is Christ’s victory over sin, death, hell, the devil, and even over God hidden in wrath (deus absconditus)—along with his law. Death is the last, greatest enemy but the law is the strangest enemy.” (“Hated God,” 23)

“It is dangerous to want to explore and comprehend the divinity by means of human reason without Christ” (SDEA, 89).

The Radical Lutherans explain to us that this “strangest enemy,” the law, even justly accused Jesus Christ! As I wrote in a past post:

[W]hat it comes down to is this: Christ ends up a damned sinner, “defeated” by that most coercive and even killing of forces: the merciless “order keeping” law!

What do I mean?

By “order keeping” I mean something like this: law is not necessarily associated first and foremost – or at all! — with God’s law, the 10 commandments, but is rather anything which provides boundaries, “makes life work,” and keeps peace – all good things! What really is true, right, and just may not even need to be considered here, as this story from a good friend of mine illustrates:

“In Kindergarten I was accused of and punished for throwing a snowball at recess. I had not done it. Oddly enough, 45 years later, it still kind of hurts to think about.

In other words, even though I was not guilty of the sin for which I was punished, there was significant suffering involved on my part. I didn’t need to be the sinner to suffer for the sin of whoever did commit that sin. Although that is what I, for all intents and purposes, became.

And justice was served. The boy hit by the snowball in the face, and his parents, were satisfied. The teacher and principal upheld the law. My classmates learned from my experience.”

By “merciless,” I mean that the law, though “good” in an earthly sense, ultimately fails because it does not have the good of particular persons in mind – even Jesus!…

We are told by the Radical Lutherans that the revealed will of God is very different from–nay, the complete opposite of–the law. It is the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ: “God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting people’s sins against them.”

Unlike the law, it actually cares about both truth and individuals, ultimately aiming to save all persons in Christ through preachers! (see Romans 10).

Does this approach to this issue not cause unnecessary confusion? Should we really be wondering whether God’s will and the law of God are two completely different things? Should we really be opening up doors for those who, asserting the temporal nature of God’s law (and of course redefining “nature,” “God,” and “law” in the process!), are also eager to see it evolve in a “Hegelian” fashion or otherwise?

Who is really being the Erasmian skeptic and “enthusiast” here?

Does it really make sense that the “the law of the Spirit who gives life” is the opposite of the law? Or does it make sense that it is instead the opposite of “the law of sin and death,” from which Christ has set us free (Rom. 8:2)!?

Again, going along with the previous posts (part 3), how we size up this issue will also determine how we view the law’s role in the Christian’s conscience and life of repentance.

Here, it also does us well to note that Luther speaks of the current world as a place where we can still, in spite of the fall, speak of “the good” (SDEA 33). And to re-iterate once again, even though Luther did speak of the law in Eden in terms of it being a threat, an evaluation of his Genesis commentary reveals that in no sense did this law actually accuse or terrify Adam and Eve, who were already at peace with God.[iii] And while for Nicholas Hopman’s Luther “[w]here there is no accusation, there is no law” (Hopman, 164), we also know that in Eden this was not the case. The law was not meant to drive, by force, God’s people to this or that (Hopman, 160), but rather to inform them of and to keep them from a very specific danger, as well as being an invitation to grow in the fear, love and trust in God (again, see my longer, more detailed argument in the latest Concordia Theological Quarterly here).

And the fact also remains that the law/commands of God, used by the Holy Spirit, are always good. With the Gospel of forgiveness ringing in our ears, it guides His people in paths that are right and true and safe. If God meant for “very good” Adam and Eve to be prevented from sinning via his command in the Garden, how much more might this be true for us who have fallen and who now face not only the devil, but the fallen world and our sinful flesh?

Indeed, until the time that the law is fulfilled in us perfectly, the Christian will be at war with these three under his commander, Christ. And here, the Holy Spirit – and the good law that He brings which says “[t]he law does not want you to despair of God… it wills that you despair of yourself, but expect good from God…” – is not to be denied (SDEA 367, 369)

Whatever else can be said here – and much more must be said and will be said in the final post of this series – this much is clear: the law and gospel – just like the Holy Spirit – reveal an important truth which is exactly the same: God has an overriding desire to do good to all men (even, finally, desiring that each not despair but be saved in Christ). This holds true even as the purposes of the law and gospel are distinct and must always remain so.

When only reading some of what Luther says, it might be easy to at times get the impression that God’s Holy Spirit only brings peace and joy in the “spirit” by the perfect Gospel, and that the “flesh” is dealt with only according to the imperfect law, at odds with the Holy Spirit (and here, we might see increasing insistence from many that we deal with this or that topic in light of stricter and stricter distinctions between the left-hand and right-hand kingdoms). This kind of “practical Gnosticizing” however, does not take into account what Luther says elsewhere.

For example, in response to the 29th argument in the Second Disputation Against the Antinomians, Luther not only insists that “God preached” (vs. “God not preached,” i.e. the hidden God) is a God of law too, but that He hides also so as to not terrify us:

“God by himself, without certain signs, cannot be comprehended; and whoever searched for God in his majesty and divinity, would be crushed by the glory of God. Yet later he emptied himself and became lovable and admirable, a boy put in the womb of the Virgin and in the manger. In this way we can bear him and he becomes easy to deal with. Otherwise, a man will not see him and live. Yet clothed and dressed in human flesh, born of the Virgin and incarnate of our flesh, made our brother and flesh, I cannot dread him.

In the same way the Holy Spirit in his majesty is incomprehensible, and when he in his majesty as God reveals the law, he cannot but kill and vehemently terrify. Therefore, he at last, in order to be Consoler and Sanctifier, also becomes a Gift… the Holy Spirit as God terrifies in the law, but consoles, sanctifies, and vivifies as Gift, in the form of a dove, and in a flame of fire” (bold and italics mine, SDEA 225).

Even if the theme of the hidden God in Luther’s theology is being abused by Radical Lutherans, the proper articulation of it (this is a very nice summary) makes a critical point. The idea here is that God is a God who hides Himself, and a temptation of man is to peek into the window of heaven, trying to catch a glimpse of the “bare God” that He has not revealed to us in Scripture.

Interestingly, elsewhere in the Antinomian Disputations, we can readily discern that Luther in fact speaks of two different kinds of “bare God” in the minds of men.

There is one which, in line with the Scriptures, “speaks in his majesty,” “only terrif[ying] and kill[ing],” – and yet, being ultimately revealed as the merciful Christ who dies for the sins of the world, and who disciplines His children in love. On the other hand, those who neglect this “basic truth” of the gospel, follow “seemingly magnificent and divine illuminations and revelations” which are “in reality satanic”. Their “bare God” is an illusion, and they “finally fall into despair” (SDEA 91).

When Luther talks in the Antinomian Disputations about the law showing sin “without this Holy Spirit who is the Gift” He is nevertheless talking about the same Holy Spirit! The Holy Spirit is, in fact, the true bare God, the One who in his majesty reveals the law and convicts of sin unto salvation and not damnation (John 16-8-10).

He also reveals the true bare God, that is, the baby, born of Mary and wrapped in swaddling clothes. He is the One who still hides Himself, but now not in wrath, but in humility, simplicity, and weakness – in the human flesh of the man Jesus Christ. For us.

And He does this, for example, in the Lord’s Supper, so as not to further terrify those who have known His wrath (and what is the Radical Lutheran’s view of this Supper?) We can, really, and truly, partake of His true body and blood in peace and joy. In fact, we can have the grace of God applied to each one of us in an exceedingly personal and intimate way.

He does so through simple and humble bread and wine, and importantly, simple and humble words to believe, still “hiding” in a sense, for our sake!

What sweet Gospel this is! “Truly, you are a God who hides himself, O God of Israel, the Savior!” (Isaiah 45:15)

And, as Luther puts it, if one believes in the revealed God, Jesus Christ, Christ will “gradually also reveal the hidden God; for ‘He who sees Me also sees the Father.’” (LW 5:46 ; LW 28:126 ; see here).

Much more on this kind of thing in the final post…

FIN

Notes

[i] Hopman has written elsewhere that “the hidden God works even life in his wrath,” and “God in his wrath works life”.

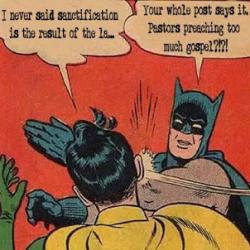

[ii] Instead of: “The law does not want you to despair of God…it wills that you despair of yourself, but expect good from God…” — Luther (ODE, 195), the view towards the law might be like what is described in this post:

“By its own standard, which cannot be violated (as a friend once told me “When the Law says ‘stone’ you stone!), the law “justly” but falsely accuses Jesus of being a sinner.

([As you say:] “Here Paul’s point is exact: the law is no respecter of persons, it does not identify Christ among sinners as an exception to the rule. Law as “blind lady justice” executes its judgment regardless of race, color, creed—or divinity.”)”

You can listen to some more official 1517 Legacy folks discuss the atonement quite well here.

[iii] See, e.g. LW 1: 62-63, 65, 111.

Images: Jörg Schubert ; The outlaw (https://www.flickr.com/photos/tinto/31228355070)