From Ch. 3, “American Lutheranism, 1961-76: A Period of Extremes”…

(Nota Bene: boldface emphases mine. — TDD)

“Gospel reductionism” was a term coined in the Missouri Synod during the 1960s. The term had its birth in the battle over the normative nature and extent of the Law and Gospel principle implicit in Lutheran theology. In the 1960s some theologians began to invoke Law-Gospel as the ruling or the only hermeneutical presupposition in Lutheran theology. They adopted this hermeneutic as a replacement for the old inspiration doctrine, which they had decisively abandoned in this period. The adoption of this method spurred a critical response by John W. Montgomery and others, such as Ralph A. Bohlmann and Robert D. Preus. Montgomery traveled around the Synod during the spring and fall of 1966 delivering papers opposing the doctrinal aberration, which he called “Law/Gospel reductionism,” among other things. Montgomery’s essays were printed in book and pamphlet form and were widely disseminated in the LCMS and beyond. In time “Law/Gospel reductionism” became known by the more compact moniker “Gospel reductionism.” Edward H. Schroeder responded to Montgomery’s charges against “Gospel reductionism” in his 1972 article, “Law-Gospel Reductionism in the History of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod.” It was universally agreed that Gospel reductionism could make a major impact on the doctrinal basis for the existence of the LCMS.

Schroeder summarized the important contributions made to Lutheran theology by C. F. W. Walther and Werner Elert, which have been reviewed in previous chapters. Their work showed the importance of the Law-Gospel principle in Lutheran theology. However, Schroeder went beyond what Walther and Elert had taught about Law and Gospel. For Schroeder, Gospel reductionism became more than just a way of denominating the Lutheran habit of judging doctrine based on metatheological themes, such as justification, which is the obverse of the Law and Gospel coin. Law and Gospel was the biblical hermeneutic of the Lutheran church for Schroeder. This approach generated a firestorm of opposition.

How could such an apparently Lutheran approach to theology generate such significant opposition? The principle of Gospel reductionism itself was not the problem. The problem of Gospel reductionism revolved around its meaning, extent, and relationship to other significant Lutheran principles of theology. Schroeder, among others, was using Gospel reductionism as a principle of biblical interpretation, a hermeneutic, indeed, as the only Lutheran hermeneutic.

Schroeder’s form of Gospel reductionism was criticized because it functioned as a hermeneutical presupposition rather than strictly as a theological principle. For Schroeder Law and Gospel had become “the hermeneutical touchstone” of the Lutheran Confessions. Schroeder even defended his position as consistent with a quia subscription to the Lutheran Confessions. “Thus anyone concerned with his quia subscription to the Lutheran Symbols could hardly take umbrage at anyone using the centrality of the Gospel, even ‘reducing’ issues to Gospel or not-the-Gospel, as his Lutheran hermeneutical key for interpreting the Bible.” Schroeder believed that the theologians who wrote the classical confessional documents of the Lutheran Reformation had actually functioned with just such a hermeneutical key to Scripture.

The distinction between Law and Gospel is the operating yardstick whereby the confessors practiced their Gospel reductionism. That distinction gave them a theological Occam’s razor to keep from multiplying Gospels (or from expanding the Gospel to include more and more things that one must believe) and to perceive when something was Gospel and when something was not. Thus the distinction is not a doctrine itself. But it is a procedure practiced as an auxiliary theological tool in theology and proclamation to keep the Gospel “Gospel.”

The problem with this characterization of the function of Law and Gospel in Reformation Lutheran theology is that, though it was a basis, it certainly was not the only basis for the confessors’ principled rejection of the work righteousness of the Roman Catholics. For example, when Luther and Melanchthon were confronted with the need to support their views, they repaired to a grammatical-historical exegesis of the essential biblical texts. Ralph Bohlmann, who inductively drew the hermeneutical principles employed by the Lutheran confessors from the Lutheran confessional documents, has shown this. Thus, this argument by Schroeder fails to convince because there is no evidence that the Lutheran confessors used the Gospel alone as their biblical hermeneutic.

Moreover, a serious contention remained over whether Law and Gospel was a hermeneutical principle at all. The Law-Gospel principle functioned as a principle of theology in the writings of the Lutheran Reformation, but it was not a hermeneutical presupposition in the sense that Schroeder used. Law and Gospel was a principle that led the Lutheran Reformers to reject certain teachings and practices because the teachings and practices were opposed to the Gospel or in conflict with the Gospel. For example, in the Augsburg Confession, Melanchthon used the Gospel to reject the imposition of human traditions upon the practice of the church:

They are admonished also that human traditions instituted to propitiate God, to merit grace, and to make satisfaction for sins, are opposed to the Gospel and the doctrine of faith. Wherefore vows and traditions concerning meats and days, etc., instituted to merit grace and to make satisfaction for sins, are useless and contrary to the Gospel.

The practice of the church was to be normed by the Gospel, so the practices that contradicted it could not be tolerated when they implied that forgiveness of sins was merited by their observance. This principle was drawn from Scripture; it was not a presupposition used in the interpretation of Scripture or imposed upon Scripture. Stricte dictu, it was not a biblical hermeneutic.

Holsten Fagerberg, whom Schroeder criticized, pointed this out for the doctrine of justification in the Lutheran Confessions. “But this doctrine is not a general key to the Scriptures. Instead of being the sole principle for the interpretation of the Scriptures, it provides the basic rule which clarifies the Scriptural view concerning the relation between faith and good works.” The same can be said of the Law and Gospel theme in the Lutheran Confessions. The Law and Gospel theme had extensive norming significance in Lutheran theology, but it was itself normed by the text of Scripture. Fagerberg stated precisely, “The confessional statements on Law and Gospel do not contain any general orientation for the interpretation of the Bible.” Kurt Marquart provided a more nuanced criticism of the Gospel reductionistic approach to use the Gospel as the sole norming authority.

Of course justification, or the Gospel in its strictest sense, is the heart and soul of, and therefore the key to, the entire Scripture. And just because the Gospel permeates the entire Scripture (always presupposing the Law), the Scripture-principle is Gospel-authority. Hence it is always and only actual Bible texts, that is the “certain and clear passages of Scripture,” and not some “Law and Gospel” floating above them, which constitute the “rule” for interpretation!

The Gospel or Scripture choice reflected a false either/or. Therefore, Schroeder’s claim that the Gospel reductionistic hermeneutic was the hermeneutic of the Lutheran Reformation was gravely flawed.

The use of Gospel reductionism as a hermeneutical tool had significant effects upon the approach to the third use of the Law. This result can be seen in the essays of Robert J. Hoyer in The Cresset, the magazine of Valparaiso University. Hoyer stated that Law and Gospel interpreted Scripture and were used to norm preaching and teaching in the church. For Hoyer, Law and Gospel are to be used to elicit meaning from the biblical text. The distinction was not just a theological filter, but a biblical hermeneutic.

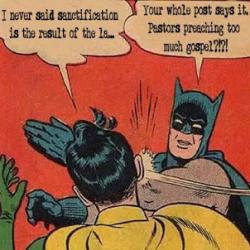

As already shown Gospel reductionism reduced authentication of points of Lutheran doctrine to whether they were “Gospel or not-the-Gospel.” With such a sharp razor of discernment, the third use of the Law is ripe for excision. The Law immediately comes under scrutiny as “sub-Gospel.” Schroeder suggested that George Stöckhardt critiqued the third use of the Law using the razor of Gospel reductionism already in 1887. While the determination of the validity of this claim remains outside the parameters of this discussion, Schroeder definitely was leading to a decisive break from the Lutheran doctrine of the third use of the Law. This use of the Law-Gospel hermeneutic is set into sharp relief by the writings of Hoyer. The Law could only judge and condemn and no more. The Law “can not really tell man what to do leading to a proper relationship with God.” There could be no ethical use of the Law whatsoever. In fact, to use it as an ethical tool would be rebellion against the Law itself. “The ethical use of the Law is that rebellion.” Basing his argument on Romans 1, Hoyer asserted that the only ethical causation attributable to the Law is rebellion against God. The Law’s only purpose is condemnation. For Hoyer, not even civil or social righteousness remains for the Law. In a short 1968 article, Hoyer advocated anarchy. “Yes, anarchy is what I propose. The proposal may be folly because of human weakness. Grace is the solution to human weakness.” The third use of the Law has absolutely no place in this approach. Not even the first use of the Law survives these presuppositions.

The simplicity of the principle of Gospel reductionism leads to abuse. Because of its simplicity, theologians can easily use it to criticize central Christian teachings, such as the validity of the Law in the life of the Christian. There is a serious threat of a severe reduction of Christian doctrine to a bare Gospel, which is no Gospel at all. A further difficulty implied by the simplicity of the principle is that it can be radically interpreted so as to rule out significant and central Christian doctrines. One person’s Law might be another person’s Gospel. The lack of an anchoring certainty troubled the critics of these Gospel reductionistic techniques. For Schroeder, Gospel reductionism functions without being anchored in authoritative texts and even functions to judge the meaning and applicability of the text of Scripture. Ironically, Law-Gospel reductionism functioned to rule out the third use of the Law. Thus, in the end, Schroeder had reduced Law-Gospel reductionism to be truly only Gospel reductionism, and that based on an extremely narrow definition of Gospel.

(Rev. Dr. Scott R. Murray, Law, Life, and the Living God, Concordia Publishing House: St. Louis, 2001. 103-107)

+SDG+