One of the most freeing aspects of Lutheran theology is gaining an understanding of the proper distinction between law and gospel. This emphasis is one of the distinctive characteristics of the Lutheran reformation as opposed to other reformation movements. The law and the gospel each have a distinct role to play in the salvation of man. The law demonstrates man’s inability before God, and failure to obey. The gospel grants the forgiveness of sins through the proclamation of Christ’s work for sinners. In his great work The Proper Distinction Between Law and Gospel, C.F.W. Walther shows that a proper understanding of each of these teachings is essential to the pastoral task. When a sinner is struggling with guilt, the pastor must preach the gospel. When someone is content in their sin, they need to hear God’s convicting law.

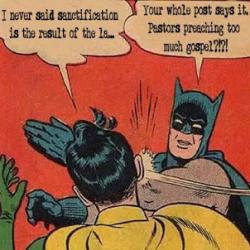

When people discover a new idea, they often become overzealous and overemphasize that particular idea. In the twentieth and twenty first century, there have been many Lutherans (theologians, pastors, and laity alike) who have discovered the distinction between law and gospel, and unfortunately, have emphasized that reality to the exclusion of all others. When this happens, the law-gospel distinction is no longer a description of how God speaks, but becomes an overarching theological paradigm. When this occurs, law and gospel are no longer doing what they are supposed to do.

The major difference between law-gospel reductionism and a traditional law-gospel distinction is that there is a confusion between the opera dei (works of God) and the verba dei (words of God). For the law-gospel reductionist, the law and the gospel are no longer defined by what they are, but by what they do. The gospel then is identified with life, and the law with death. Now, certainly, the law does bring death in a coram deo (before God) context. Before God’s holy throne, the law can only accuse the believer. However, traditional Lutheran theology has always confessed that there are three uses of the law. In its third use, the law functions in a positive role. It serves as a guide for the believer, so that one might learn what works please God, and what sins one must avoid. This is the description of the law in Psalm 119, where the law becomes a delight to the person of faith. In a law-gospel reductionist schema, since the law is identified with death, there is no place for a traditional third function of God’s law. The third use is either denied, or redefined so that it too becomes a “killing use,” just as the second is.

Lutheran theology is full of great dichotomies: law and gospel, sin and grace, two kinds of righteousness, two kingdoms, saint and sinner, etc. The fact is that all of these theological categories are an absolute necessity, and when we let one be a controlling theological paradigm over the others, problems can arise. Instead of, then, seeing law (command) and gospel (promise) as the two ways in which God speaks, they become an overarching theological structure. Every passage of Scripture, then, must be interpreted as either “law” (usually in its condemning use), or “gospel.” Every sermon, then, is supposed to utilize law and gospel as a structure. First, preach law. Second, preach gospel. I recently heard someone claim that the pastor shouldn’t even exposit a Biblical text from the pulpit, but instead preach the law and then the gospel!

Don’t get me wrong, I love the distinction between law and gospel. I think it is an invaluable theological category, and it guides much of my pastoral ministry. However, we can’t force the distinction to do more than its meant to. It is especially valuable in explaining our relationship to God. We are sinners, and fail to obey God’s commands. Before his law, we are condemned. Yet, God provides a solution to our sin in the gospel, where Christ grants us his own righteousness. But law and gospel doesn’t explain how one relates to others (that’s the two kinds of righteousness), how we function in society and the church (that’s the two kingdoms), or the entirety of the application of salvation (that’s the ordo salutis). If we only speak of law and gospel in terms of death and life, there also is essentially no place for positive instruction for the Christian, or for growth in sanctification.

Being balanced is difficult. We all have our pet issues that we want to talk about. Yet, we need to try and speak about all of God’s word. There are passages that speak about good works, the Christian’s role in society, and piety toward God. If your theological schema does not allow you to preach or speak about these passages, you might be a law-gospel reductionist.