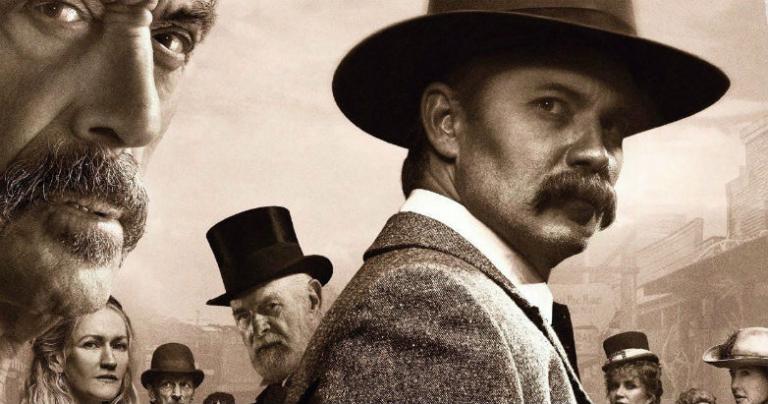

If you’ve never seen Deadwood, I hardly know where to start, other than to say it’s time for a serious binge, capped off by the movie-length conclusion, airing Friday, May 31, on HBO. But gird your loins, children, it’s a rough ride.

I did such a binge myself over the past couple of weeks, powering through all three seasons of the 2004-2006 HBO series (only one of multiple viewings over the years) about the gradual incorporation into America of a lawless mining camp in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory in the 1870s, seen through the eyes of a mix of fact-inspired and fictional characters.

If I need to elaborate further on the show and its vast cast of ragged gold miners, prostitutes, pimps, saloon keepers, gunslingers, fortune hunters and so on — and its copious helpings of foul language, violence and sexuality — well, that would take up the whole piece. So, you can click here and here to learn more or just go watch and come back later.

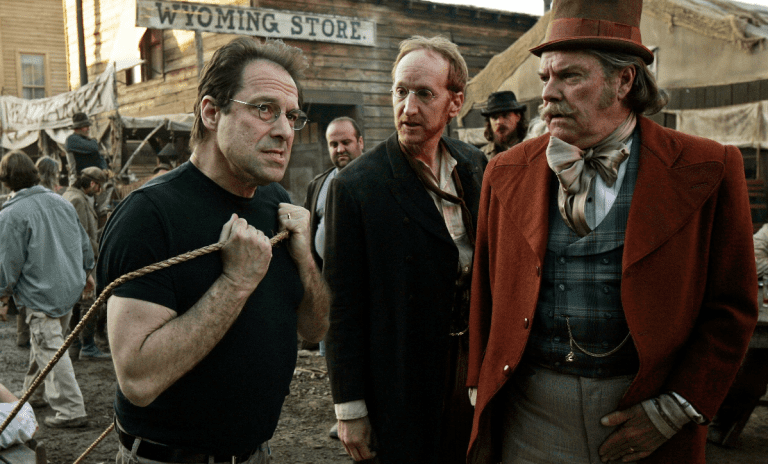

Suffice to say that nearly as many from the original Deadwood as remain alive (on the show or in real life) or were available have returned. The sets, built at Melody Ranch in Newhall, California — surrounded, last time I was there, by a development of very expensive houses — were meticulously restored and updated, since the movie takes place in 1889 (the New York Times goes into detail on that here).

During my long sojourn as an entertainment journalist for the Tribune syndicate, I did many interviews on Deadwood and visited the set many times. So, I watched the series again through a jumble of memories: lunches with creator David Milch near his office in Santa Monica; standing behind him on the set of the Gem Saloon, as Seth Bullock (Tim Olyphant) got his sheriff’s star from saloon keeper, gangster and unlikely town father Al Swearengen (Ian McShane); sitting with actor Titus Welliver on steps beside the thoroughfare, watching with wonder the passage of horses and the most colorful cast of extras you could imagine; prime rib, homemade ice cream and Turkish coffee at lunch; watching the gardens planted on the location grow; walking off the thoroughfare into the fully built first floors of the Bella Union saloon, the Bullock and Star hardware store and gold magnate Alma Garrett Ellsworth’s (Molly Parker’s) house.

Deadwood always smelled of fresh-cut wood, leather and horse manure, and that’s not a bad thing.

One of my fondest memories is sitting at a West Hollywood restaurant listening to John Hawkes, who played Bullock’s Jewish partner, Sol Star, tell Olyphant about his recent trip to the real Deadwood (Hawkes was shy talking to me, but not to his co-star — thanks, Tim).

It’s also hard for me to separate Deadwood from its creator, David Milch. A singular talent who managed to craft a kind of Shakespeare out of a pungent mixture of 19th-century locution, 21st-Century profanity and his own idiosyncratic syntax. Beset over his career by addiction and health issues, Milch was always possessed of an outsized talent and an expansive spirit, which he expressed with gifts of time, expertise and money.

Over months, he tutored me in screenwriting (a career I’ve finally embarked upon, with some early success), and showed immense kindness at a difficult moment in my life — and I’m far from the only one to say that.

Milch collected characters of all kinds and was mentor to many. The news that came out, during publicity for the Deadwood movie, that he has Alzheimer’s, is heartbreaking for any that know him (click here for a New Yorker piece that goes into that in detail).

Over his time in television, from Hill Street Blues through NYPD Blue to Deadwood, Luck and more, Milch has battled many of his own demons. In his life, he was a heroin addict, an alcoholic, spent time in a Mexican jail and lost vast sums of money on the ponies.

So, he has a certain understanding of those who do bad things but may, under it, have good hearts. Like many towns, especially in the American West, Deadwood was founded by people who’d felt the need to leave somewhere else: outcasts, ne’er-do-wells, fortune hunters and even some decent folk desperate for a better life. Polite, comfortable people seldom leave all they know to strike out in the wilderness.

While Deadwood may have (OK, did) exaggerate the degeneracy and fiddle with the facts of most of its historical characters, allowing for perhaps a Milchian excess of contemporary four-letter words (a constant bone of contention during the show), the show wasn’t far off in depicting the precariousness of life in places like this filthy mining camp.

But underneath the language, the raw sex, the sometimes random deadly violence, the constant abuse of women (who, surprisingly, in Milch’s world, sometimes hold their own and give back as good as they get), and the rampant greed, was a warm and beating heart. People surprisingly show compassion, if roughly, kindness and even tenderness. Even those quick with a knife have a conscience and their limits. The death of innocents is not taken lightly.

When prostitute Trixie (Paula Malcolmson) speaks of her abortions, she doesn’t dress it up. She says, “I killed seven.”

Faith also wound its way through the whole show. I once jokingly accused Milch, who’s Jewish, of being “half a closet Catholic,” since Christian expression in his show often had a decidedly Catholic cast. As one example, in the throes of agony from bladder stones, Swearengen cries out, “Mother of God!” — not something most Protestants are likely to say. In the movie, he exclaims, “Mary and Joseph and all the risen saints!”

Saloon owner Tom Nuttall (Leon Rippy) once remarks to Swearengen, “Well, I’ve always believed, of all His sufferings on the Cross, His busted ribs would have hurt Him the worst.”

More generally, prostitutes read the Bible and pray for their pimps. Characters not infrequently quote Scripture. Hymns are sung. A sweet-natured reverend (Ray McKinnon) in the first season is a ray of kindness and light, making friends and presiding over funerals, even as he suffered from a brain tumor. When Swearengen finally “sees to him,” as he puts it, it’s an act of mercy.

However badly the characters act, few act as if they think there’s no God. They may throw their sins in His face, but they believe He’s there, nonetheless — and several turn out to be repentant (fans, note who’s the new minister in the movie).

At the end of the Deadwood movie, the Lord’s Prayer is begun, and Swearengen continues it in his own defiant way.

Deadwood is a place of sinners in need — and even search — of a merciful God. In truth, as polite or civilized as they may seem on the surface, all places are.

Deadwood, the series, is available on DVD and for streaming on HBO NOW, HBO GO, On Demand and Amazon Prime. Deadwood: The Movie is available at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT, on Friday, on HBO NOW and HBO GO, and On Demand on Saturday, June 1.

Image: HBO

Don’t miss a thing: Subscribe to all that I write at Authory.com/KateOHare.

And, head over to my other home, as Social Media Manager at Family Theater Productions; and check out FTP’s Faith & Family Media Blog, and our YouTube Channel.