Who was Billy the Kid? Outlaw? Avenging angel? Cold-blooded killer? Or, as the new EPIX miniseries about him, premiering Sunday, April 24, suggests, “More sinned against than sinning?”

Maybe so.

A New View of a Legendary Outlaw

There’s a lot of revisionist history going on these days. Much of it is slanted and one-sided — making former heroes look like villains, and former villains look like heroes. But we all know that life has always been way more complicated than that.

In the eight-episode first season of Billy the Kid, writer Michael Hirst (Vikings, The Tudors) illuminates the short but memorable life of Henry McCarty — a k a William H. Bonney, a k a Kid Antrim, a k a Billy the Kid — born to Irish Catholic immigrant parents in New York City in 1859.

With his parents and younger brother Joseph, the boy Henry heads west. The trip proves too much for his father, leaving his devout mother Kathleen (Eileen O’Higgins) a young widow. She struggles through the difficult life of the 19th-century West, finally marrying a Presbyterian named Henry Antrim (Jamie Beamish) — giving her son another one of his names.

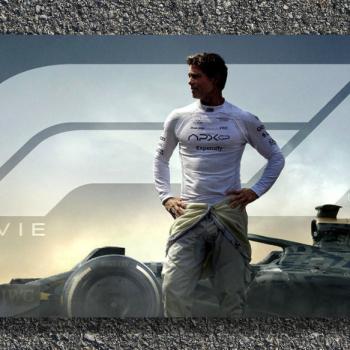

By his teen years, Henry loses both his brother and mother, and begins calling himself William H. Bonney, leading to the nickname Billy. In real life, Billy the Kid was 5’3″, but in the series, 6′ tall British actor Tom Blyth (heiress Gladys Russell’s brief suitor in HBO’s The Gilded Age) plays the adult Billy.

He has a moral conscience, provided by his mother (represented by a little Madonna and Child statue she gives him), and Billy wants to do the right thing. But, over and over again, his vulnerability and merciless circumstances force him into risky and criminal behavior.

He falls in with rustler and robber Jesse Evans (Daniel Webber), who becomes his best pal and almost shadow self. He’s where Billy will end up if he lets his conscience go entirely.

Along the way, Billy’s lack of prejudice regarding Mexicans and Native Americans stands out (I’ve read that the historical record confirms that), and he speaks fluent Spanish.

The Cross Over Billy the Kid’s Shoulder

While we never see Billy enter a church, they figure prominently in the landscape in the show’s main settings of New Mexico and Mexico.

Occasionally, a priest passes by, or the cross atop a mission-style church hovers over his shoulder, or someone actually hands him a scapular (points to Hirst for even having heard of one). Shooting someone while he’s praying is a major turning point for Billy, representing a sharper (but not permanent) turn to the dark side.

Hirst has never been known to shy away from Christianity as an element in his work. But whether you attribute Billy’s morals to God or the memory of his mother, or both, it appears that Billy really was this sort of complex character.

For sure, he killed people and likely escaped the same fate himself many times, but he never robbed a bank, stagecoach or train, and he never got rich.

Fighting an Old Word Feud on New World Land

The West could make it near impossible for a good person to stay that way, and on his travels, Billy meets all kinds. He winds up in the employ of an Irish-born businessman/landowner, who’s at odds with a British-born businessman/landowner — transplanting an ancient feud to Lincoln County, New Mexico.

Ultimately, which is stronger — blood and loyalty or doing what’s right? Billy’s family came to America in search of justice for all, and Billy doesn’t want to give up on that ideal.

The legend of Billy the Kid is bigger than the life of Henry McCarty. Every tale about him is some mix of history and mythmaking. I don’t suppose Hirst’s script is any different.

We do know that Billy the Kid’s life was short. It ended at, depending on what you read, 21 or 22. But at the end of the show, it’s obvious that we’ve got a ways to go. So, if the show gets renewed, I’m hoping that Hirst includes the story of his encounter with an extraordinary nun.

The Nun Who Stood Up to Billy the Kid

The Archdiocese of Santa Fe is promulgating the sainthood cause of Italian-born nun Sister Blandina of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton’s Sisters of Charity. She was known for her sanctity, and her work as a teacher, caretaker for the sick and imprisoned, etc. in Colorado and later New Mexico, regardless of ethnicity, faith or means.

As for her connection with Billy the Kid, a 2013 article in Crisis magazine relates an 1876 encounter:

Reality and myth are interwoven in the stories of the outlaws of the American west, but that gangs of desperadoes prowled the plains and mountains seeking easy prey is true enough. There were a number of gangleaders who went by the name “Billy the Kid,” William Bonney being only the most famous of them. In 1876 a henchman of Billy the Kid—whether it was Bonney or some other Billy is uncertain—was injured by a gunshot taken during a quarrel with a fellow outlaw.

He was left to die, and none of the area’s four physicians would lift a finger on his behalf. Sister Blandina visited him frequently over the ensuing weeks, offering both physical and spiritual comfort. While the fellow was incapacitated, Billy the Kid and his men returned to Trinidad to visit their comrade and to exact vengeance on the town’s doctors. Having been apprised of Blandina’s efforts, Billy offered that she might request a favor of him. She asked him to spare the lives of the four physicians. He agreed, and left town in peace. The wounded outlaw never recovered, dying later that year.

What’s the Verdict on Billy the Kid?

Hirst’s telling of the outlaw’s story is sympathetic to his faith — and faith in general — well-balanced and fair-minded. I’d watch another season.

NOTE FOR PARENTS: Beautifully shot in Calgary, Alberta, Billy the Kid has violence, of course, but it’s not excessively gory. There’s also language sprinkled throughout and some relatively restrained (especially for premium cable) sex scenes. I can’t offhand recall any fully lit nude scenes. But there’s enough of all of the above to limit it for high-schoolers and up.

Image: EPIX

Don’t miss a thing: Subscribe to all that I write at Authory.com/KateOHare