Premiering Monday and Tuesday, April 4-5 on PBS (check local listings), Benjamin Franklin: A Film By Ken Burns profiles perhaps the most enigmatic of the Founding Fathers — who was also a man of faith, if not the most orthodox sort.

Born the 10th son of a Boston soap maker (he was legitimate, unlike his own son, and that son’s son and grandchildren, making for a strange Franklin family tradition), Franklin ended his formal schooling at age 12.

A self-taught polymath, he went through careers as a printer, writer, editor, businessman, social organizer, inventor, amateur scientist and economic envoy to England before, late in life, he ever got involved in helping to birth the American republic.

Historian Walter Isaacson and Ken Burns Discuss Franklin

At the recent TV Critics Association (virtual) Winter Press Tour, Walter Isaacson, author of The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin, addressed the complex nature of Dr. Franklin (whose doctorate was honorary), saying:

The importance of Ben Franklin is that he was able to connect art and science, able to connect the humanities and technology. He cared about everything you could possibly learn about anything, from art to anatomy to math to music to diplomacy.

And his science helped inform the things that he did. By being an expert in Newton, he understood checks and balances and balances of power.

His electricity experiments are the most important scientific achievements of that period, right after Newton. And, so, I do think by being like a Renaissance man, like a Leonardo da Vinci, he’s able to see the patterns in nature.

And he thought of himself as a scientist and an inventor. I think that is engrained not only in him, but into what the foundation of America was about.

Ken Burns picked up the thread, saying:

Yeah, I think Walter’s exactly right. You’ll be happy to know in a couple years we’ll be coming back with a film on Leonardo.

Many of these projects born at a dinner in Washington D.C. many years ago, when we realized we couldn’t divorce the right and the left brain and we couldn’t divorce either of these two, sort of, protean figures who are arguably among the most important human beings, certainly for Franklin in the 18th century.

Whatever History Thinks, Franklin Knew He Wasn’t God

Fellow Founding Father John Adams realized that history would view Franklin as a towering figure, as he said in an April 4, 1790, letter to another Founder, Benjamin Rush:

The Essence of the whole will be that Dr Franklin’s electrical Rod, Smote the Earth and out Spring General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his Rod—and thence forward these two conducted all the Policy Negotiations Legislation and War.

But what Adams and Franklin — and likely Washington as well — knew is that there was, above them, a Supreme Being.

Benjamin Franklin deals with its subject’s less-than-conventional view of Christianity. Franklin often gets called a Deist, a believer in a clockmaker God who doesn’t interfere in our daily lives. He did refer to himself as a “thorough Deist” in his autobiography, but that’s only part of the story.

Likely closer to the truth is this passage — included in part in the documentary — as described in a post at the Pennsylvania Heritage website:

Ezra Stiles (1727-1795), the Calvinist president of Yale College, was curious about Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) and his faith. In 1790, he asked the nation’s senior statesman if he would commit his religious beliefs to paper. Franklin agreed.

He was nearing the end of his life – he died six weeks later – and possibly believed this was as good a time as any to summarize the religious creed by which he lived.

“Here is my Creed,” Franklin wrote to Stiles. “I believe in one God, Creator of the Universe. That He governs it by His Providence. That he ought to be worshiped. That the most acceptable Service we render to him, is doing Good to his other Children. That the Soul of Man is immortal, and will be treated with Justice in another Life respecting its Conduct in this …

“As for Jesus of Nazareth … I think the system of Morals and Religion as he left them to us, the best the World ever saw … but I have … some Doubts to his Divinity; though’ it is a Question I do not dogmatism upon, having never studied it, and think it is needless to busy myself with it now, where I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble.”

The narrative was classic Franklin, witty and to the point. Religion was worthless unless it promoted virtuous behavior. Jesus was the greatest moral teacher who ever lived, but he was not God.

Franklin and Slavery — It’s Complicated

The four-hour Benjamin Franklin film — which, in form and presentation, is classic Ken Burns — leans heavily into Franklin’s inconsistent comments and actions in regard to chattel slavery.

In this, he was hardly alone among the Founding Fathers.

Eventually, Franklin came down on the right side of the issue, but he still had to support the compromises in both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution that ensured the Southern states would first join and then remain in the union.

Said Isaacson:

The greatest thing they had to do as founders, and the greatest thing we have to do in our lives, is to know when to compromise and when to stand true on principle.

Franklin is a great example of that. He usually gets it right. He knows you can’t make a great democracy without compromise, but there’s times where he says you can’t compromise.

He, and they, got it wrong, especially on the three‑fifths clause, and Franklin knew it, which is why he dedicated the rest of his life after the Constitutional Convention to being an abolitionist, to decrying the notion of slavery, to trying to get rid of it, and, even more so than even Lincoln, believing that Blacks could be well-educated and were just as capable as whites. And, so, he becomes somebody who promotes education as well.

But you have to understand in life when you’ve messed up and been willing to compromise when you should have stayed true to principle, just as you have to understand the times when you’ve messed up and taken a high moral position but screwed things up because you couldn’t compromise.

A Nation Born From Compromise and Original Sin

As a documentary producer, Burns generally steers a middle ground. But, like anyone else in the filmmaking business, he’s affected by the outside culture.

If done ten years ago, Benjamin Franklin might not have delved as deeply into the issue of slavery. But, this is a vital part of the story of the founding of America, and it’s undeniably part of Franklin’s personal and political story.

It’s obvious that Franklin knew that, one day — in this world or the next — he and his fellow Founders would be called to task for their compromises … but they still had to make them.

Perhaps Peter Stone’s book/screenplay for the musical/movie 1776 captured it best:

Dr. Benjamin Franklin: We’ve no choice, John. The slavery clause has got to go.

John Adams: [stunned] Franklin, what are you saying?

Dr. Benjamin Franklin: It’s a luxury we can’t afford.

John Adams: [pause, then] ‘Luxury?’ A half million souls in chains … and Dr. Franklin calls it a ‘luxury!’ Maybe you should have walked out with the South!

Dr. Benjamin Franklin: [dangerous] You forget yourself, sir. I founded the FIRST anti-slavery society on this continent.

John Adams: Oh, don’t wave your credentials at me! Maybe it’s time you had them renewed!

Dr. Benjamin Franklin: [angrily] The issue here is independence! Maybe you have forgotten that fact, but I have not! How DARE you jeopardize our cause, when we’ve come so far? These men, no matter how much we may disagree with them, are not ribbon clerks to be ordered about – they are proud, accomplished men, the cream of their colonies. And whether you like them or not, they and the people they represent will be part of this new nation that YOU hope to create. Now, either learn how to live with them, or pack up and go home!

[pause, then]

Dr. Benjamin Franklin: In any case, stop acting like a Boston fishwife.

While We’re on the Subject of Overlooked Bits of History

Speaking of aspects of the American Revolution that are not widely covered, I recently finished listening to the audiobook of British historian Andrew Roberts’ excellent biography The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III.

One of Roberts’ missions in the book, if not the chief one, is to rehabilitate George III’s reputation in the face of the widespread belief (first codified in the Declaration) that he was a tyrant.

History has perhaps judged George III unfairly on this, but one thing that struck me was the huge role that anti-Catholicism played in the Revolution — on both sides of the conflict.

Burns might want to consider including this bit of history in a future film.

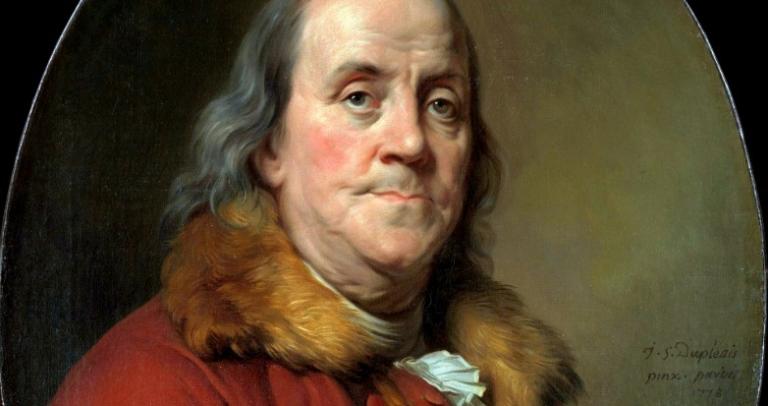

Image: Benjamin Franklin portrait by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, 1778/Credit: Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Don’t miss a thing: Subscribe to all that I write at Authory.com/KateOHare