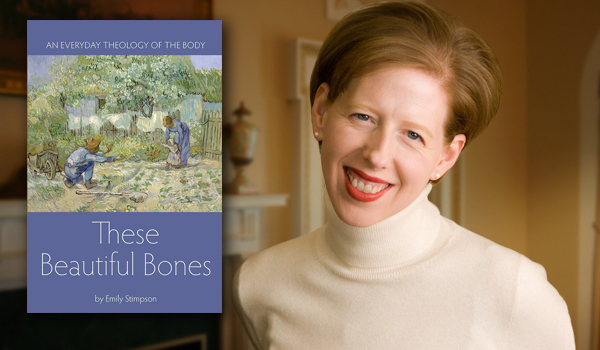

Earlier this fall, I interviewed Emily Stimpson about her wonderful book, These Beautiful Bones: An Everyday Theology of the Body, published by my friends at Emmaus Road, for National Review Online. I subjected her to extra questions so that there would be more to share. This seems like as good a time as any to do so. Some of you are looking for good, quality, potentially life-changing gifts for loved ones for Christmas. Some of you might find yourselves with a gift card for Amazon before the end of the month, or just looking for a book that will help set the new year a-right.

Upon my first read of These Beautiful Bones, I said:

The phrase “feel it in our bone” comes to mind when considering the theology of the body, the New Evangelization, and all great efforts of renewal and catechesis. We have to feel the love of God in our bones, we have to believe that our very bones at made in love to know and serve Him with, before we can fully understand and share the teachings the Church on the most intimate and controversial of issues. Emily Stimpson helps unpack Blessed John Paul II’s Theology of the Body in the most practical and accessible of ways, so that we can see its meaning in every aspect of our lives. It’s a beautiful, saint-making manual. And as we’ve come to expect from Emily, her approach is enriching and practical, communicated with joy, honesty, courage, compassion, and love.

I think of how much pain so many people are in, whether it is regret, shame, illness, or struggle to see themselves as the loved children of a merciful Father they are. This book can help.

Let Emily talk to you about it.

KJL: Was putting bones in the title your attempt at making your book a Halloween hit?

EMILY STIMPSON: Not quite, but it’s not a half-bad idea. I’ll talk to the publishers about rejiggering a marketing campaign for next fall. In all seriousness, the title comes from the opening and concluding chapters, which are something of a meditation on the Capuchin Bone Church in Rome. The month before I began working on the book I visited the church for the first time and was struck by how much of what I wanted to write about was already written into the very design of the church.

KJL: How can we all possibly be called to be saints?

STIMPSON: I ask God the same thing every day. Sometimes it seems like if he wanted me to be a saint, he should have given me some better raw material to work with. But the call remains. Understanding how that’s possible becomes easier if you spend time with the saints. The more you read their actual words or the stories of their lives, the more you stop thinking of saints as consumptive 14-year-old virgins and start seeing them as real men and women—men and women who sinned and struggled their way to perfect love of God in their own wild, singular, and often downright quirky way. Besides, all it means to be a saint is to be the person God made you to be. It means to be you, uniquely and perfectly you, free from all the fears and sins and lies that keep you from being the person you’re supposed to be and from loving God as he made you to love him. Becoming that person isn’t easy. But it is simple.

KJL: You don’t seem to care much for academic discussions. Got Garrigou-Lagrange? But do you mention him for theological street cred?

STIMPSON: It’s not that I don’t care for the academic discussions. We need them. For example, tracing Garrigou-LaGrange’s influence on John Paul’s thought is especially important for reassuring skittish Thomists about TOB (and yes, tossing his name around does make it sound a bit more like I know what I’m talking about). But those discussions, for as important as they are, aren’t all we need. We need the little discussions too—the ones about how the theology of the body can help us in all the ordinary moments of life. And, ultimately, I do think those discussions are the more important ones. That’s because John Paul II didn’t give us the theology of the body so we could debate it in classrooms or write about it in academic journals. He gave it to us so we could discover who we are and live authentically human lives.

KJL: How can laundry and lice ever be joyful? Seriously.

STIMPSON: They’re joyful when you put them on a sliding scale. Laundry and lice are bad. Broken hearts are worse. That’s the context in which I tell the story of how weeks and weeks of battling a lice infestation helped me cope with a bout of boy troubles. What I discovered during those weeks is that there is real joy in physical labor, a joy that comes from doing what angels can’t do, using our bodies to subdue the earth (or an out of control lice population) and dominate creation (or our laundry rooms). So often, in a culture where most of us sit at desks all day, we don’t get to experience that joy. The lice gave me the opportunity.

KJL: Not to be too literal but is there a spiritual reason to actually do the dishes and not use the dishwasher?

STIMPSON: I don’t know if I would call it a spiritual reason, although there can be something very therapeutic about hot water and soap. I guess you could say that the sum total of all our labor saving devices, while good in many ways, has made it easier for us to avoid the joys and lessons that come with manual labor. We’re a bit more disassociated from our world because technology does so much of our work for us. That being said, I’m not giving up my dishwasher anytime soon.

KJL: What does the theology of the body offer men?

STIMPSON: It offers them a lesson in what it means to be a man, in what it means to love as a husband, father, brother, and son. It shows them the dignity and the importance of manhood, as well as how they can live out that dignity in their homes, offices, and communities. Lastly, it shows them how essential they are to healthy families and a healthy culture. That’s a truth our culture tends to downplay these days, denigrating men and the gifts they bring to their families and society. And we’re all paying the cost for that. The theology of the body shows us why.

KJL: Is “spiritual parenthood” just a coping mechanism for the unmarried, non-priest/nun Catholics?

STIMPSON: I know it can sometimes come across that way. It’s tempting to think of spiritual parenthood as a consolation prize for those not blessed with children of their own. But spiritual parenthood isn’t a task for only those without children. It’s a task for people with children as well. It’s a task parents are called to exercise in their homes, and it’s a task we’re all called to exercise in the world. Women who have 10 children and women who have no children are equally called to love everyone they meet with a mother’s love—to see the beauty in a person and then nourish and nurture that beauty, loving that person as they most need to be loved. Men are likewise called to love everyone they meet with a father’s love—to challenge, encourage, and serve them, just as fathers challenge, encourage, and serve their own children. Our failure to do that is one of the reasons our world is in the mess it’s in.

KJL: The last time I interviewed you on your last book, you got some interesting responses. What did you make of that?

STIMPSON: I learned not to take strangers’ evaluations of my marital prospects too seriously.

KJL: Without a common vocabulary about just about anything can we really talk about “disordered desires”?

STIMPSON: We can if we start with examples that have nothing to do with sexuality. Most of us have spent our entire lives hearing that there is no such thing as a disordered sexual desire, that all sexual desires are good. Accordingly, it can be difficult to shake that idea. We know, however, that we have other desires that are “disordered.” We all desire to do things that are not good for us: skip out on yoga class, sleep in and miss work, eat deep-fried pickles, waste time on Facebook. You get the picture. All those things aren’t bad in themselves (except for maybe the deep-fried pickles), but when we desire them too often, at the wrong times, or in the wrong ways, they become bad for us, which means our desire for them is disordered. If that holds true in every other area of life, why would we think it wouldn’t hold true in the sexual realm as well? Good desires for good things—whether those things be food or sex—can always become twisted and unhealthy.

KJL: What did you love most about writing the book?

STIMPSON: I’m not supposed to say being done with it, am I? But, that’s kind of the truth. I’ve been thinking and working through these issues, both in my life and my writing, for more than a decade. Finally fleshing them all out in one place where I had the room I needed to explore the concepts was wonderful, and now seeing them all neatly packaged in one complete book, is even better.

KJL: What did you struggle with?

STIMPSON: Choosing which aspects of “everyday life” to write about. It’s a pretty big subject. The theology of the body has so much wisdom to offer on so many of the bits and pieces of life, and there was no way I could address them all. In the end, I tried to select the subjects on which I thought I had the most to say or which were the most fundamental, but there is definitely room for disagreement on that question.

LOPEZ: Is theology of the body one big Humanae Vitae was right party?

STIMPSON: How do you have a party about all the sad predictions made by Humanae Vitae coming true? In 1968, Pope Paul VI predicted that if the world reduced the purpose of sexual love to mere pleasure, divorcing the act from the creation of new life, then we would see widespread marital breakups, out-of-wedlock births, material poverty, and the spiritual poverty that comes for both men and women when women are seen and treated as sexual objects. And we have. The theology of the body doesn’t celebrate Humanae Vitae being right. It shows us the way back to sanity, to seeing the body and sexual love rightly once more.

In our NRO interview, Emily points out:

“Theology of the body” refers to a series of meditations given by John Paul II during his papacy. It answers some of the most pervasive and fundamental questions that all men and women across time have asked: Who am I? For what purpose do I exist? What does it mean to love? How am I to live?

You don’t have to be a theologian to care about those questions, and you definitely don’t have to be a theologian to read my book. I don’t focus on the philosophical and theological subtleties of theology of the body. I’m all about the practical, nitty-gritty application of it. So, what does the theology of the body have to do with eating Twinkies, running on a treadmill, or watching Dr. Who? Those are the questions I’m interested in, so those are the questions I address in the book.

There may just be a young person — or any person — or yourself who could use this book about now.