Deacon Greg Kandra, over at The Deacon’s Bench, had this story:

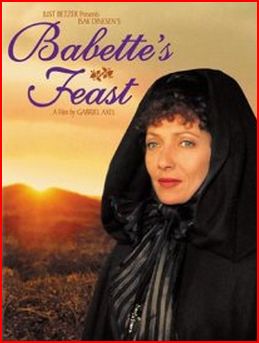

Gabriel Axel, the director whose 1987 film “Babette’s Feast,” received the first foreign-language Oscar awarded to a Danish motion picture — and heralded a growing popular interest in all things food — has died in Copenhagen at the age of 95.

And according to the New York Times obituary, Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, told journalists in 2010 that “Babette’s Feast” was his favorite film.

It’s my favorite film, too! Which is why I’ve resurrected an old post I’d written about it here.

CAN AN AGNOSTIC BE DIVINELY INSPIRED?

“Babette’s Feast” Is a Eucharistic Allegory

From an Unlikely Author

You probably know at least a little about Danish baroness and plantation owner Karen von Blixen-Finecke. She was the heroine (Meryl Streep) who had a passionate but ultimately doomed love affair with a free-spirited big-game hunter (Robert Redford) in the 1985 romantic drama Out of Africa. She was an author who wrote under the pen name “Isak Dinesen.”

You probably know at least a little about Danish baroness and plantation owner Karen von Blixen-Finecke. She was the heroine (Meryl Streep) who had a passionate but ultimately doomed love affair with a free-spirited big-game hunter (Robert Redford) in the 1985 romantic drama Out of Africa. She was an author who wrote under the pen name “Isak Dinesen.”

But you may not remember that she was an agnostic.

My husband and I recently pulled out our copy of the film “Babette’s Feast” (Danish:Babettes Gæstebud), which won the 1987 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. The story was originally published, I understand, in Ladies Home Journal—and it was recreated in film by esteemed Danish writer and director Gabriel Axel.

“Babette’s Feast” is Dinesen’s parable about two spinster sisters who, once beautiful young women, had forsaken their chances at romance and fame, taking hollow refuge in religion and caring for their father, a pastor of a stern Christian sect in a rough Danish coastal town.

The sisters are named Martine (after Martin Luther) and Philippa (after Luther’s close friend Philip Melanchthon). [This is an important factoid—more on this later.]

* * * * *

The spinster sisters are approaching old age when Babette Hersant appears at their door carrying a letter of recommendation from Philippa’s former suitor. Babette is a refugee from the French counter-revolution; and the sisters cautiously agree to take her in as a housekeeper. For fourteen years, Babette works as their cook and housekeeper—gradually warming the town with her generosity and pleasant demeanor. One day, she wins the French lottery; but rather than return to her hometown, she decides to use the money to prepare a delicious feast for the sisters and the small religious congregation on the founding pastor’s hundredth birthday.

The spinster sisters are approaching old age when Babette Hersant appears at their door carrying a letter of recommendation from Philippa’s former suitor. Babette is a refugee from the French counter-revolution; and the sisters cautiously agree to take her in as a housekeeper. For fourteen years, Babette works as their cook and housekeeper—gradually warming the town with her generosity and pleasant demeanor. One day, she wins the French lottery; but rather than return to her hometown, she decides to use the money to prepare a delicious feast for the sisters and the small religious congregation on the founding pastor’s hundredth birthday.

Babette, in a lavish expression of generosity, spends her entire winnings on the banquet. Not simply an epicurean delight, the meal is the means by which Babette expresses her gratitude and her love for the sisters who sheltered her.

The wary townspeople—unprepared for such a lavish pallet of strange new foods, distrustful of a Catholic foreigner such as Babette, and unaccustomed to joy—secretly determine to eat the meal without commenting, to consume without truly appreciating the generous repast.

But as the guests experience the rich flavors and beautiful presentation of the extraordinary banquet, they are moved—and they are gradually transformed by joy. The director amplifies this joy with color, focusing on the delectable dishes, bringing a pallette of rich colors into the cool whites and grays of the sisters’ modest home. And as the color intensifies, so, too, does laughter and pleasure and love.

* * * * *

What does it all mean?

- The Washington Post called Babette’s Feast “edible art,” a tour de force for the taste buds.

- Marjorie Baumgarten, writing in the Austin Chronicle, called it the “food in film” equivalent of Valhalla.

- Christopher Null at filmcritic.com sees in Babette’s Feast a seminal work about repressed emotions and self-doubt.

A foodie film? A gloomy story of repression?

Well, yes but…. for a Christian, the parallel to the Eucharist, to a heavenly Feast, is striking.

- In her sacrifice, her pouring out of her resources in an expansive love, Babette is a riveting Christ-figure.

- The satiating meal, an earthly parallel to the heavenly banquet, is eucharistic.

- And the grace it imparts, the rich outpouring of emotion among the gloomy Danish congregants, mirrors the spiritual life-giving nourishment of the Eucharist.

But curiously, Isak Dinesen herself seems to have been limited by her secularism, incapable of applying the story’s imagery within the context of faith. Raised in a Unitarian household, she drew upon the Old and New Testaments and other spiritual works for her themes; but she remained an agnostic, never raising her eyes toward the heavens to gaze upon the transcendent God. Her personal life was marred by a failed marriage and unsatisfying relationships. She was addicted to painkillers, and she died in 1962 of malnutrition—starving both physically and spiritually.

So to the question in my title: Can an agnostic be divinely inspired?

My answer is a resounding “Yes.” It seems that Dinesen reached beyond herself, beyond her wildest imaginings, to reveal a Truth which she, lacking true faith, could not understand.

* * * * *

Now about Martine and Philippe, and their famed namesakes Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon:

Melanchthon, the younger and lesser known friend of Martin Luther, labored with him to reform the church. However, there is an interesting difference between the two: Whereas Luther stood firmly on his self-constructed platform of “justification by faith,” Melanchthon was more moderate. He agreed that one must have faith; but also, he taught, one must demonstrate one’s faith by works.

The two friends are buried side by side at the Castle Church in Wittenberg. I’ve read that Martin Luther has a statue of Mary at his grave.