An undergraduate student assisting at an archeological dig on Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula has made a spectacular discovery: a 400-year-old copper crucifix.

The crucifix is considered particularly important since the colony which once stood at that spot was English, and Catholics were severely persecuted in England at the time. It was, then, most likely owned by someone who fled religious persecution in England and found freedom here.

Anna Sparrow, who attends Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland, was painstakingly sifting through dirt at the site when she found the crucifix, solidly packed in a clump of dirt. According to CBC News, the copper cross is just three centimeters wide, with its top portion missing. It depicts the crucifixion of Christ on one side and the Virgin Mary on the reverse.

Barry Gaulton, associate professor of archeology, called the find “an important part of North American history.”

“When Anna first found it, my heart sort of stopped for a minute and I knew it was a crucifix,” Gaulton told CBC News.

“Back in England, you could be fined, imprisoned or put to death for practising Catholic faith, so Calvert had different plans for Newfoundland and one of his plans was religious toleration, religious freedom. This artifact is a direct manifestation of that toleration, so it’s an important part of Canadian history.”

* * * * *

Sparrow and other students were digging on the site of a former colony which had been established by Baron George Calvert, an early Newfoundland governor.

Calvert had held high political office in England; but he resigned his post in 1625. Calvert had always been interested in exploration and settlement in the New World, even purchasing a share of the second Virginia Company in 1609. Five years before his resignation, he had purchased a tract of land in Newfoundland from Sir William Vaughan. Calvert named the plantation he founded there Avalon (on what is now called the Avalon Peninsula), after the legendary spot where Christianity was introduced to Britain in ancient times.

Calvert did not immediately travel to the New World himself. Instead, he dispatched Captain Edward Wynne and a group of Welsh colonists to Ferryland, where they landed in August 1621. The immigrants, many of whom most likely left England in search of a land where they could openly profess their faith, began the ambitious task of constructing a settlement.

* * * * *

RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION IN ENGLAND, AND FREEDOM IN THE NEW WORLD

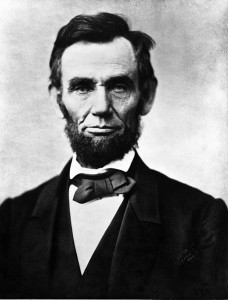

(Lord Baltimore)

Four hundred years ago in England, when George Calvert was serving as a Member of Parliament and later Secretary of State under King James I, Catholics were not permitted to hold public office. When Calvert fell into disfavor in the court, he resigned from office and was granted a post as First Lord Baltimore in County Longford, Ireland.

Some historians believe that Calvert was a secret Catholic, even during his years on the king’s court. In any case, when he left his post as Secretary of State, he immediately converted to Catholicism. George Abbot, the Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote of Calvert at the time that political opposition and the loss of his office had

“made him discontented and, as the saying is, Desperatio facit monachum, so hee apparently did turne papist, which hee now professeth, this being the third time that he hath bene to blame that way [sic]”.

Godfrey Goodman, the Bishop of Gloucester, later claimed Calvert had been “infinitely addicted to the Catholic faith”–a secret Catholic all along. This, Goodman believed, explained his support for lenient policies towards Catholics.

Once in Avalon, Lord Baltimore adopted a policy of free religious worship in the colony, permitting the Catholics to worship in one part of his house and the Protestants in another. This unusual arrangement proved too much for the resident Anglican priest, Erasmus Stourton—”that knave Stourton”, as Baltimore referred to him—who, after altercations with Baltimore, was placed on a ship for England. Once back on British soil, Stourton reported Lord Baltimore’s practices to the authorities, complaining that the Catholic priests, Fr. Smith and Fr. Hackett, celebrated Mass every Sunday and

“doe use all other ceremonies of the church of Rome in as ample a manner as tis used in Spayne [sic]”.

Further, Stourton complained, Lord Baltimore had had the son of a Protestant forcibly baptized into the Catholic faith. Stourton’s complaints were investigated and then dismissed.

A SAD ENDING TO THE STORY

Lord Baltimore grew weary of life in what he called “this wofull country” after a harsh winter, during which nine or ten of his fellow colonists died. Half of the settlers were sick at one time, so that Lord Baltimore’s house had to be converted for use as a hospital. He sent his children home to England, and he and his wife departed for Virginia, where he attempted to found a mid-Atlantic colony.

However, the Virginians in Jamestown were vehemently opposed to Catholicism, and ordered him to leave. After only a few weeks in the colony, he left for England without his wife and servants. He later sent a ship to bring them back; but the ship was caught in a storm and his wife drowned off the coast of Ireland.

Things grew worse: He lost his fortune and was forced on some occasions to depend on the generosity of friends. In the summer of 1630, Lord Baltimore’s household was infected by the plague, although he survived. Still a man of faith, he wrote to his friend Wentworth:

“Blessed be God for it who hath preserved me now from shipwreck, hunger, scurvy and pestilence…”

Finally, in 1632, things seemed to be looking up. The King granted Baltimore a charter for a piece of land south of Jamestown. Because of tension with some settlers who sought to establish a sugar plantation, Baltimore petitioned the King for a change. In the end, a compromise was reached; Baltimore would lay claim to land with redrawn boundaries to the north of the Potomac River, on either side of the Chesapeake Bay.

However, before he could take charge of the property, he died in his home. His son Cecil inherited the title Lord Baltimore and the imminent grant of Maryland.