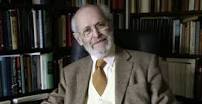

Geza Vermes (1924-2013) was a British, Jewish scholar born in Hungary who lost his parents in the Holocaust. Reared Roman Catholic, he attended a Catholic seminary and became a Catholic priest. He became a leading authority on the Dead Sea Scrolls as well as the historical Jesus. This Oxford professor received many honors, including being a Fellow of the British Academy. In his career, Geza Vermes understandably vascillated between being a Catholic Christian and being a Jew.

Geza Vermes (1924-2013) was a British, Jewish scholar born in Hungary who lost his parents in the Holocaust. Reared Roman Catholic, he attended a Catholic seminary and became a Catholic priest. He became a leading authority on the Dead Sea Scrolls as well as the historical Jesus. This Oxford professor received many honors, including being a Fellow of the British Academy. In his career, Geza Vermes understandably vascillated between being a Catholic Christian and being a Jew.

Due to his several books about Jesus of Nazareth, Vermes may have been most responsible for developing what N. T. (Tom) Wright later labeled “The Third Quest” of the historical Jesus. It has been an emphasis on the Jewishness of Jesus which was much needed mostly because the church had made Jesus into sort of a Gentile Christ. Vermes helped establish that Jesus’ ministry was a reform movement in Judaism.

I have several of Vermes’ books in my library, and I have read most of them. They include his triology: Jesus the Jew (1973), Jesus in his Jewish Context (1983), The Religion of Jesus the Jew (1993). But I also have The Changing Faces of Jesus (2000) and The Authentic Gospel of Jesus (2003).

Geza Vermes’ books about Jesus are stimulating. For a scholar, he is a very clear writer who is easy to understand. I was drawn to reading his books partly because he was a leading historical Jesus researcher who was Jewish, and, as I do, he did not believe the New Testament ever identifies Jesus as God. Yet I have found it difficult to accept Geza Vermes as a genuine Christian. Why?

One of Geza Vermes’ last books was about Jesus’ resurrection entitled The Resurrection: History and Myth (New York: Doubleday, 2008). Like most historical-critical scholars, in this book Vermes makes it clear that he does not believe in the literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus. Frankly, I was disappointed because in his previous books he had not been so clear about this.

One of Geza Vermes’ last books was about Jesus’ resurrection entitled The Resurrection: History and Myth (New York: Doubleday, 2008). Like most historical-critical scholars, in this book Vermes makes it clear that he does not believe in the literal, bodily resurrection of Jesus. Frankly, I was disappointed because in his previous books he had not been so clear about this.

For me, the resurrection of Jesus is the foundation of Christianity. Without Jesus’ resurrection, I don’t think there ever would have been any Christianity. The Apostle Paul wrote to the saints at Corinth defining “the good news” (=gospel) as being “that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas [Peter], then to the twelve” (1 Corinthians 15.1, 3-5 in the NRSV and throughout herein). Paul added, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied” (vv. 15.17-19).

Vermes’ small book is divided into two parts. Part One (pp. 1-55) is about ancient Jewish belief regarding the possibility of an afterlife and what the Jewish Bible (Old Testament) says about it. Part Two (pp. 57-148) is about New Testament teaching about resurrection and, more particularly, about whether or not Jesus was literally, bodily raised from the dead.

Vermes rightly shows that the Old Testament (OT) does not have the emphasis on resurrection that the New Testament does. He claims that the Hebrew people did not have a belief in resurrection and that Jews during the Second Temple period gradually adopted this belief. He cites Daniel 12.2 as the primary OT text verifying a future resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked. It says, “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.” Vermes also cites Isa 26.19 as a text indicating the future resurrection of only the righteous. Like almost all biblical scholars, Vermes believes that the book of Daniel was written during the second century BCE (I disagree) so that Jewish belief in resurrection was only then coming into vogue.

Yet, during the time of Jesus, Jews in Israel were divided on the concept of a future resurrection. The Pharisees believed in resurrection, as did Jesus. But the Sadducees–who controlled the religious life in Israel and therefore administered all things worship regarding the temple in Jerusalem–did not believe in a future resurrection or any kind of afterlife. Neither did they believe in the existence of angels or the possibility of miracles. Thus, even though they were religious, the Sadduccees were rationalists.

Thus, near the end of Jesus’ public ministry the Sadduccees tried to entrap him by asking a hypothetical question about levirate marriage and the resurrection (Deut. 25.5-10; Matt. 22.23-28 and parallels). Jesus answered nost forthrightly, “You are wrong, because you know neither the scriptures nor the power of God. For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven. And as for the resurrection of the dead, have you not read what was said to by God, ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’. He is God not of the dead, but of the living” (vv. 29-32). So, Jesus gave a subtle indication of resurrection from scripture that long preceded the two scriptural texts that Geza Vermes cited.

Vermes does rightly state that the OT repeatedly teaches about human souls residing in Sheol after death. Sheol is mentioned 67 times in the Hebrew Bible (OT). Vermes says (p. 15), “the underworld, the Sheol of the Bible” is “identifical with the Hades of the Greeks” and the Greek NT.

And Vermes well informs (p. 30), “Palestinians Jews came up with the idea of bodily resurrection, while their brethren in the Greek-speaking Diaspora opted along Platonic lines for immortality of the liberated soul, enjoying divine bliss after escaping from the ephemeral and corruptible body.” Indeed, the Greeks ridiculed the Apostle Paul when he preached at the Areopagus in Athens about the future resurrection of the dead and the judgement (Acts 17.30-32). Greeks despised the idea of bodily resurrection, and some claimed that at death righteous souls, which are immortal, immediately go to heaven. Vermes cites (p. 40) the the famous Jewish philosopher-theologian Philo, a contemporary of Jesus, who embraced this Greek belief about afterlife. The majority of Christians eventually adopted this Platonic belief even though it is contrary especially to the OT.

One of the things I enjoy about reading Vermes’ Jesus books are that, being a Jewish scholar, he does well in presenting the culture in which Jesus lived. He cites (pp. 47-50) one of the Jews’ Eighteen Benedictions as affirming the concept of the future resurrection, and although this document was drafted in the second century CE, he says it indicates that a majority of Jews in Israel during the time of Jesus would have believed in the resurrection due to the influence of the Pharisees. Yet he says (p. 50), “in the age of Jesus, Pharisee presence in Galilee was scarce if it existed at all.” That is something I have noticed from the NT gospels.

In this book, Vermes frustrates me as he examines the various resuscitations from the dead mentioned in the Bible without clearly distinguishing between them and bodily resurrection until p. 60. (See especially pp. 135-36.) For example, Jesus’ raising of his friend Lazarus from the dead was a resuscitation, not a resurrection (John 11.38-44). Thus, even though scripture does not inform us, Lazarus would have later died again. But in the resurrection of the righteous dead, they become immortal and thus will never die.

Vermes adopts the traditional understanding of the Gospel of John (e.g., p. 67), with which I disagree, that it proclaims Jesus preexisted and that he is God, all of which Vermes dismisses as false.

All three synoptic gospels report that during the latter period of Jesus’ approximately three-year itinerant ministry he predicted privately to his disciples that he would be killed at Jerusalem and rise from the dead the third day afterwards (Matt. 16.21; 17.22-23; 20.18-19 and parallels). Vermes rightly states of these (p 79), “all the predictions are couched in clear and simple language that no one could possibly misunderstand.” Vermes then treats briefly Jesus’ prediction about his resurrection being on “the third day.” Gentile Christians have been quite silent about this, but Jews have a long history of recognition of a third-day motif in their scriptures. Vermes well explains (p. 81), “it is more likely that the expression was chosen because it was a typical Old Testament formula marking seven significant biblical events occurring ‘on the third day.'” He then cites Genesis 22.4 and Hosea 6.2 as most prominent. He also explains the “three days” in place of “third day” as being that “according to rabbinic reckoning, part of a day or night counted as a full day or night (yShabbath 2a; bPesahim 4a).” (See my book on this, The Third Day Bible Code.) In a departure from most historical-critical Jesus researchers, Vermes does well in saying (p. 82), “one must conclude that the predictions by Jesus of his death and Resurrection and his reference to biblical prophecies about his suffering and glorification are authentic.”

Vermes tries to establish a contradiction between the synoptic gospels and the Gospel of John regarding the burial of Jesus’ corpse. He insists (p. 90) that Joseph of Arimathea, “Without the use of the customary spices, he wrapped the body in a linen shroud.” Vermes then mentions what the Gospel of John says about the matter and concludes (p. 94, “It goes without saying that John is substantially at variance with the Synoptics.” Not at all. The synoptics briefly mention a single “cloth” (Gr. sudarion) whereas John 20.5-7 has the word in the plural three times. I think the synoptics refer to the roll of linen cloth that Joseph probably purchased at a shop in the marketplace whereas the Fourth Gospel relates the process of wrapping the body with strips of cloth taken from this single roll.

I was constantly frustrated with Vermes identifying the several post-resurrection appearances of Jesus in the NT gospels as “apparitions” and “visions.” Some Jesus’ researchers do likewise yet believe in Jesus’ bodily resurrection. I vehemently maintain that they are neither and that such suggests a denial of Jesus’ resurrection. And I think Vermes is deceptive in this book by always capitalizing Jesus’ “Resurrection.” Yet the reader does not know that the author clearly does not believe in Jesus’ resurrection until near the end of the book.

Like so many NT scholars nowadays, Geza Vermes (p. 102) describes the gospels’ post-resurrection appearances of Jesus as “the confused and often contradictory data contained in the Gospels and in chapter 1 of the Acts of the Apostles,” which he also calls “discrepancies.” Vermes adds (p. 112), “Their accounts display numerous inconsistencies.” I beg to differ. But to address all these points would make this review way too long. Plus, I have already addressed some of this material in previous posts and my three-part review of Bart Ehrman’s book How Jesus Became God.

If some of these historical-critics had become private investigators, they would have starved to death! It shows how biased they are toward historical inauthenticity of the NT gospels. They make so many unwarranted assumptions. It should be a lesson to devout Christians to be careful when commenting on the biblical text.

Vermes is like most distinguished NT scholars and all historical-critical scholars in his assertion that Jesus said, and the early Christians believed, that Jesus would return soon after his heavenly exaltation, at least within a generation (e.g., Matt. 24.34/Mark 13.30). I most strongly disagree with this. Of course, it makes Jesus into a liar since it has been nearly 2,000 years now, and he still has not returned. For example, Vermes says of Jesus’ disciples (p. 138), “They were convinced that the Parousia [Second Coming] was at hand and would happen within in their lifetime. They would witness it before their death…. The Resurrection as such did not concern them.” (I have a book manuscript on this subject which I intend to have in my Still Here series.)

In chapter 15, “The Meaning of the Concept of Resurrection in the New Testament,” Vermes does a good job in setting forth six foremost theories skeptics have proposed concerning Jesus’ empty tomb and belief in his resurrection (pp. 141-48). They are: (1) The Body Was Removed by Someone Unconnnected to Jesus, (2) The Body of Jesus Was Stolen by His Disciples, (3) The Empty Tomb Was Not the Tomb of Jesus, (4) Buried Alive, Jesus Later Left the Tomb, (5) The Migrant Jesus, (6) Do the Appearances Suggest Spiritual, Not Bodily, Resurrection? Since Vermes believes the supposed post-resurrection appearances of Jesus in the NT gospels were apparitions or visions, he is inclined to believe this last, number 6, skeptical theory. He says (p. 147-48), “Spiritual resurrection is best associated with visions and appearances…. Resurrection as a spiritual entity is appropriately expressed as a vision.” However, Vermes admits (p. 148), “none of the six suggested theories stands up to stringent scrutiny.”

I hesitatingly recommend Geza Vermes’ book, The Resurrection: History and Myth. But I caution that even though he does not believe in Jesus’ resurrection, which I regard as supremely important, readers can benefit from much of the other material that Vermes writes about Jesus.