Acts 2:1-21 or Ezekiel 37:1-14

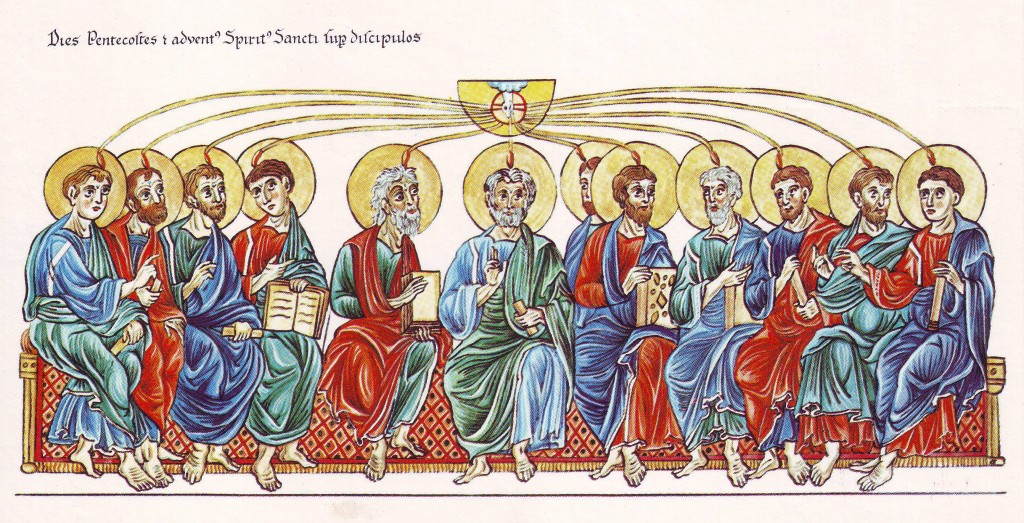

What It’s About: The lectionary provides two options here. And since this is Pentecost, they are both about renewal, new life from old, and the restorative and sustaining work of God. The Acts text is the story of Pentecost, with the divided tongues as of fire. The Ezekiel text is the vision of the valley of the dry bones. These are, for my money, two of the most inspiring passages in the bible, and it would be a shame to have to pick between them. Fortunately, you don’t have to!

What It’s Really About: These are both stories about hope springing forth from less-than-hopeful situations. In Ezekiel, the proximate circumstance is a valley of dry bones (not a great start for a story about life), and the more general context is one of destruction and national tragedy. In Acts, the setting is the aftermath of the crucifixion, when the disciples of Jesus must have felt confused and abandoned. Into all of these circumstances, across both narratives, we remarkable infusions of hope.

Since Pentecost is about the birth and ongoing renewal of the church, these are powerful texts to have at your disposal. They are inspiring, and they point to the ongoing inspiring presence of God within the church.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about the other texts below, if I’m preaching. Those are all great, but with these two as a starting point, I would absolutely be using one of these, if not both.

Maybe You Should Think About: How does the Ezekiel text challenge some traditional descriptions of Judaism? Christians are fond of saying that the God of the Old Testament is a God of judgment, punishment, and law, and that the God of the New Testament is a God of mercy, grace, and new beginnings. This is, of course, silly if you read the bible very much, and this verse from Ezekiel is a great example of that. Which God do you see here? To me, it looks like an Old Testament God of grace, new beginnings, and hope.

What It’s About: This is a psalm in praise of God through the wonders of the earth. It is about the sea, the mountains, and all the known and mysterious creatures of the world.

What It’s Really About: There’s no artifice here; that’s what it’s about. I have a running list in my head of times and places I would visit if a time machine ever gets invented, and somewhere around #10 on the list would be Jerusalem, maybe 2700 years ago, because of psalms like this. What was the life setting of the community that would produce a psalm like this? We can read it in familiar ways, to comport with our own modern ideas about the environment and spirituality, but of course that is importing modernity into antiquity. So I’d really love to know just what was in the air back then to produce a psalm like this, not to mention the creation stories and the last chapters of Job.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about 35a! The presence of an “a” or “b” in a verse designator is a sure sign that something offensive, disturbing, or weird is being edited out, and in this case what’s being cut is a line about the wicked and the sinners being removed from the earth. So it’s worth remembering, as we ask that question above about what kind of worldview this psalm could come from, that whatever worldview that was, included the notion of sinners being wiped away.

Maybe You Should Think About: There are maybe some ways to connect this psalm to the other texts for the day, especially the Ezekiel and the Romans below, but in some ways it stands apart. Maybe think about ways to connect them creatively?

What It’s About: This is about creation, humanity, and the pregnant hopefulness of God’s world.

What It’s Really About: This text is really about Paul’s labyrinthine and elliptical way of writing. On that list of places and times to visit when they invent a time machine, wherever Paul was would be right at the top of the list. He writes without much expectation that people like us would be reading (or preaching) his words, so he doesn’t say things as clearly as we might have liked. And here, he slides through a few different -ologies in one chapter—some eschatology, some pneumatology, some soteriology, and some cosmology. The result is opaque and beautiful in the way Paul can sometimes be.

What It’s Not About: This isn’t about us, in the same way Paul’s writings are never about us. To understand this passage, you have to think about his audience in Rome, mostly unknown to him since he didn’t found that church. You have to think about what Paul thought they thought, which is quite the feat of gymnastics, across twenty centuries. But to me the most resonant part of this passage is the image of the woman groaning with labor pains, ready to bring forth something new to the world. If that’s how Paul really thinks about the world, and if that’s how we are meant to think about the world, what does that do for our visions of the cosmos? If what’s coming is birth, and not death as Christian culture so frequently assumes, how does that change how we live?

Maybe You Should Think About: Paul knew his scripture. That’s pretty clear from his writings. So I wonder, when Paul was writing something like this, whether he had in mind something like the Ezekiel passage? Did Paul think about the coming birth in the world in terms of the valley of dry bones? They’re very different metaphors, of course, but some of the themes really resonate. Picking Paul’s brain would be my #1 priority once they build that time machine.

What It’s About: This is about the Advocate, the Paraclete in Greek, who is coming after Jesus. This is usually identified with the Spirit in Christian thought, although the two are in some ways distinct ways of talking about the ongoing work of God in the world. The Spirit is mentioned in this passage, so it’s possible that the author of John thought of them in the same kind of way.

What It’s Really About: Yet another thing on my list of time machine destinations would be the Johannine community, circa the year 80. There are wonderful theories about this community, and about the ways that their communal life might have shaped the gospel of John. I like to think that this passage, where Jesus promises that God’s work will be ongoing, is a response to a time when the community felt abandoned or forsaken, and they needed reminding that God was still there. If that’s true, then it puts that community in real connection with our own communities, and it makes this passage a great one to preach—especially in conjunction with the message of Pentecost.

What It’s Not About: Compare 16:5 with 13:36 and 14:5. There are a few places in John where the seams are visible—where the sources from which the gospel were compiled are visible. This is one of them, where one phrase is used in different ways to make it pretty clear that one part hasn’t always been related to the others. This passage isn’t really about that, but it’s interesting to me.

Maybe You Should Think About: How is an “Advocate” different from a “Spirit?” And are they telling us the same things about God, or different things?